Sassetta, detail of the Funeral of St Francis, panel from Borgo San Sepolcro altarpiece, 1437-1444, National Gallery, London

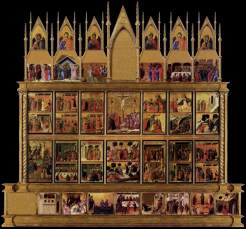

It must have been a strange procession that wound its way from Siena to the town of Borgo San Sepolcro in the late Spring of 1444. The renowned Sienese painter Stefano di Giovanni (ca. 1392-1450), known as Sassetta, the carpenter who had crafted the frame and perhaps Sassetta’s close colleague Pietro Giovanni d’Ambrogio with other assistants arrived in Borgo with the enormous polyptych commissioned by the Franciscans of the convent of San Francesco seven years earlier. The altarpiece would have been transported in separate units: its predella, main tier, pilasters and pinnacles would be assembled on the spot. The men would also have brought with them dowels, iron devices, nails and tools for the carpenter (in all likelihood the one responsible for constructing the altarpiece’s frame back in Siena) to install the painted structure on the high altar. Sassetta had come not only to oversee the installation but also, if necessary, to repair any paintwork that may have sustained damage during transportation.

On June 2nd Sassetta’s polyptych was installed on San Francesco’s high altar which had been erected exactly 140 years earlier to commemorate Blessed Ranieri, a local Franciscan friar. The townspeople would have flocked to the church to see the new altarpiece. It had come from afar: the more usual practice was to erect structures on altars to be painted in situ, but on this occasion the first time the people of Borgo laid eyes on Sassetta’s majestic polyptych was in its finished and mounted form on the altar. Among the eager viewers were the young Piero della Francesca, a native of the town, and his master Antonio di Giovanni d’Anghiari. The two had failed to complete the altarpiece commissioned from them for the same church which was now replaced by Sassetta’s polyptych.

The installation of Sassetta’s altarpiece is uniquely recorded by Ser Francesco de’Larghi, notary and chancellor of the town, who, among the customary dry notarial acts recording sales, receipts and testaments, noted:

On the second day of the month of June [1444], which was the third day of Pentecost, the altarpiece painted and decorated by Stefano of Siena was placed on the high altar of the Church of San Francesco in Borgo. Benedictus Deus.

The polyptych stood on the altar of San Francesco for over a century. During the Counter-Reformation the altarpiece was dismantled but several panels still remained in the church, mounted on other altars as recorded by Apostolic Vicar Angelo Peruzzi who visited the church in 1583 and noted a “beautiful picture with beautiful framework” on one of its altars.

The cult of Blessed Ranieri and the Franciscans of Borgo San Sepolcro

Ranieri’s “incorrupt”corpse laid out in front of the high altar of San Francesco in 1954 on the 650th anniversary of his death

On 1 November 1304, Ranieri, a local man who was a lay brother of the Franciscan order in Borgo San Sepolcro (today: Sansepolcro) died. Nothing is known about his life other than his name, the date of his death and one or two miracles said to have taken place during his lifetime as recorded in a 1532 religious play about the friar. Probably from a poor background Ranieri would not have had a last name although in later times the family name “Rasini” came in use, however without historic foundation. It was not until after Ranieri’s death, in fact the very next day, that miracles started to occur in rapid succession, first through direct physical contact with the friar’s corpse and later by physical contact with his casket or by praying for his intervention. The Liber Miracolorum, recording testimonies of those Borgo citizens who had sought and found healing through Ranieri, survives in two manuscripts, the oldest dating from the 14th century. As many as sixty miracles are recorded for the period from his death on 1 November 1304 until April of the next year.

In Borgo San Sepolcro the climate was ripe for a local cult such as that of the Blessed Ranieri. The founding of a Franciscan convent with its church, the emergence of other confraternities as a focus for lay devotion and charity and the winning of self-government by the secular elite made that new saints were required: holy men and women who were local, therefore approachable, unburdened by high ecclesiastical office, contemporary, and who would be role models for the people. Ranieri fitted that bill exactly.

Detached fresco from the church of San Francesco by a local anonymous artist depicting Saint Anthony Abbot, Madonna Lactans, Christ enthroned and a Franciscan Saint presenting a female donor figure, late 14th century, 215×263 cm, Museo Civico, Sansepolcro. Photo MD, 2011

Towards the end of that same year, 1304, the first step was taken to propagate Ranieri’s cult: a high altar dedicated to his memory. In view of the new climate described above it is important to remember that not the Franciscans but the commune commissioned the altar. It still stands in the church today and the crypt where Ranieri rests, now in a 16th century wooden sarcophagus, is also still largely intact but in all other respects the early gothic church interior is unrecognisable today, having been rebuilt between 1752 and 1760. Only very few original architectural elements survive and the frescos that once adorned the walls, those that survived, were detached and are now on display in the Museo Civico close to the church, as are the church’s carved choir stalls with intarsia panels dating from around 1495.

San Francesco’s high altar is of dark-gray sandstone or pietra serena. It consists of an immense monolith measuring 181 x 342.5 cm which rests on a block carved with large, rectangular rosette reliefs, surrounded by an arcade consisting of colonnettes, the majority of which with a rich variety of twisting designs. In its design it followed the Franciscan typology, modeled ultimately on the high altar of the Lower Church of San Francesco in Assisi which was consecrated in 1253.

The inscription on the front of Borgo’s altar’s mensa is unique among surviving Franciscan high altars and testifies to the close links between the friars and the local community:

In the year of our Lord 1304 on the Feast of All Saints, Saint Ranieri migrated to the Lord. In that year the commune of Borgo commissioned this altar to the honour of God and the magnificence of the said saint. Amen.

Once Ranieri had been laid to rest in the crypt below the presbytery, the worshippers could see his tomb from all sides through grids in the altar steps as is still possible today, again a similar situation as once existed in Assisi.

Precedents and empty altarpieces

In 1426 the carpenter Bartolomeo di Giovannino d’Angelo was commissioned to construct a frame following the model of Sienese artist Niccolò di Segna’s altarpiece of 1340-50 in the church of the Camaldolese order (today’s cathedral) with the difference that the altarpiece for San Francesco should be prepared for painting on both sides.

Di Segna’s monumental altarpiece consists of a large panel with a depiction of the Resurrection in the center and four panels showing saints in three-quarter length on the sides. The panels are all the same height and have trapezoidal tops, but the central panel was twice as wide as the side panels. The original slender, rectangular, gilt pilasters adorned with blue paint survive with those framing the central scene are slightly thicker than those at the sides. In the upper tier, which was painted on the same planks of wood as the main section are depictions of pairs of saints under double arches. The altarpiece would have been wider than the altar on which it stood and framed on the sides by vertical buttresses, necessary to distribute the weight of such a large altarpiece. In addition, such buttresses provided space for the representation of a large number of additional saints. The existence of similar buttresses for the San Francesco altarpiece is confirmed in the commission of 1426 and the documents of 1439: the carpenter was to use a piece of iron “to sustain the necessary columns”.

When Antonio d’Anghiari was commissioned to paint the double-sided altarpiece for San Francesco in 1430, the wooden structure had already stood empty on the high altar for four years. Work still did not begin until two years later when Antonio, with the young Piero della Francesca as his assistant, started to prepare the front face. But they never actually seem to have begun painting and Antonio eventually lost the commission, perhaps because he had not been able to complete the work in the required time-span of three and a half years. He seems to have suffered from chronic poverty and may not have been able to pay the expenses of the altarpiece: the gold and pigments, among which the expensive azurite stipulated in the contract. Due to his financial distress he may also have taken on various other jobs such as repair work which meant that any progress (if at all) on the altarpiece was slow. It seems to have been left to young Piero, then about 15 years old, to gesso (ground with gypsum) the wooden structure installed on the high altar, a time-consuming and laborious task.

It should be noted that it was by no means unusual for a wooden structure to stand on an altar unpainted for a long period. An illustration of this phenomenon is a fresco in the church of Sant’Andrea, Siena, showing bare wood with no figures. To assume that this fresco is unfinished is not correct: it merely reflects a reality found in several Italian churches of the period. In one case, in Rome, it took as much as twelve years until a painter was commissioned to paint a bare wooden structure standing on a high altar. Possible reasons for this phenomenon could be that the patrons, after paying for the carpentry, needed ample time to gather enough funds to hire a painter. Often such funding was co-dependent on private donations and the sale of properties or land. In the case of the Franciscans in Borgo the process, due to its exceptional circumstances, would even take eighteen years from the initial carpentry commission in 1426 to the installation of the altarpiece in 1444.

Choosing Sassetta

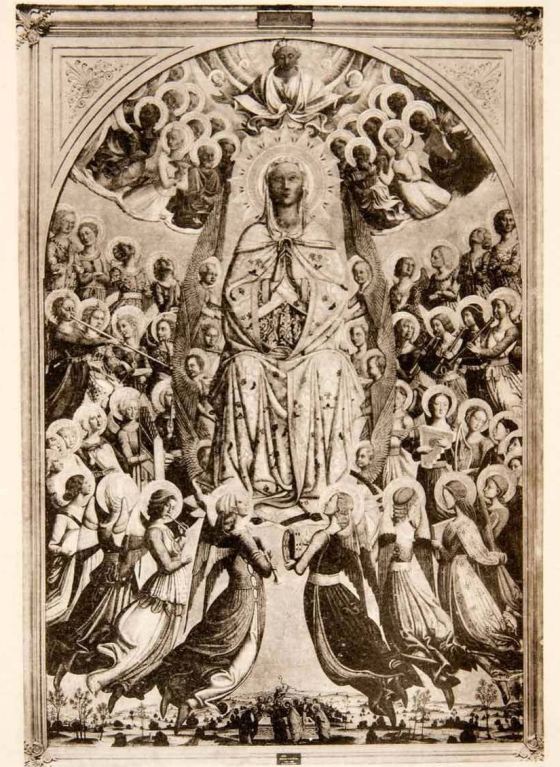

Why, after D’Angiari’s and Piero’s failed enterprise, did the friars of Borgo turn to Siena and in particular to Sassetta? For one thing, Sienese artists such as Taddeo di Bartolo and Niccolò di Segna had, in the previous century, worked frequently on distant commissions as the latter’s altarpiece for the abbey and another, now lost, altarpiece for Borgo attested so that there would have been a predilection for Sienese art in Borgo. They may have known his work from Borgo citizens traveling to Siena or from works in nearby Cortona where the painter was born. Another factor may have been the painter’s association with Bernardino from Siena, the Franciscan order’s most celebrated preacher. As Machtelt Israëls suggests, Sassetta very likely painted a large Assumption of the Virgin for the Osservanza convent church in Siena in the 1430s (previously thought to post-date the Borgo altarpiece) while the celebrated and influential Franciscan preacher Bernardino was in residence.

Sassetta, Assumption of the Virgin surrounded by angels, mid-1430s, tempera and gold on panel, 332×224 cm. Formerly Kaiser Friedrich Museum, Berlin (destroyed in 1945)

It is, however, not likely that Bernardino himself had anything to do with a Franciscan commission for a small conventual convent in the back waters at Borgo San Sepolcro although his association with the painter may have helped: any control of the subject matter and the execution of the altarpiece was after all the responsibility of the Borgo convent as its commissioner. Certainly, by commissioning the Sienese painter who was then at the height of his artistic powers, conveys the ambitions of the Franciscans of Borgo and possibly a conscious intent to compete with and even outshine the older altarpiece in the town’s abbey.

What made Sassetta especially suitable for this ambitious undertaking was his ability to translate spirituality into intimate imagery, something that would have appealed especially to the Franciscans: colour pitched to the subtlest intensity, figures that are almost flimsy, almost naive, set in fluid, intricate architecture. He had also proved that he was immensely versatile and could adapt his style when a commission demanded it. His Wool Guild (Arte della Lana) altarpiece (1423-25) was an ingeniously movable, highly elaborate gothic altarpiece used by the guild for its outdoor celebration of the Feast of Corpus Domini and otherwise stored in the guild’s palazzo. Although today only a few fragments survive, these are indicative of Sassetta’s artistic ambition and the stylistic and aesthetic aims he sought to achieve.

Sassetta’s art is unmistakably Sienese in its mysticism and refinement rather than analytical such as Florentine art of the period. He made constant reference to his great Trecento predecessors such as Duccio, Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti but he did so in such a way that it emphasised his “modernity” at the same time: his heightened flat colours and abstracted space are closer, perhaps, to Bonnard and Matisse than Masaccio. His indebtedness to Pietro Lorenzetti’s altarpiece for the Carmine in Siena of a century earlier is evident in the astonishingly complex architecture of the Wool Guild panels. Although these do not yet demonstrate a full understanding of perspective, the interiors are completely coherent and innovative.

Sassetta, predella panel of the Arte della Lana altarpiece: St Thomas Aquinas at prayer, 1423-25, tempera and gold on panel, 24×30 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

For instance, in the scene depicting Saint Thomas Aquinas at prayer, the figure of the Saint kneeling in front of an altar surmounted by a splendid polyptych is minimal; nothing more than a black pedestal surmounted by a haloed egg. The real emotional vehicle is the spatial setting which juxtaposes interior and exterior, inviting us out into the cloister garden with its fountain as well as deep into the monastic library with its terraced rows of desks lit by stained glass windows. All is precisely and independently envisioned and subtly illustrative of the Saint’s monastic life. Only when we notice the grey dove of the Holy Spirit descending does this space take on full significance. Aquinas’ writings provided the foundation of the liturgy of Corpus Christi and here, kneeling before the altarpiece of the Virgin, he receives divine inspiration. The natural beauty, the waters of the well, the books on their reading desks: on all this Thomas has turned his back to embrace instead devotional solitude.

Sassetta, Madonna della Neve, 1430-32, tempera on panel, 240×216 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

The frame of Sassetta’s Madonna della Neve (Madonna of the Snow) altarpiece for a chapel in Siena’s Duomo (1430-2) has survived intact so that it is possible to understand Sassetta’s ingenuity and use of historical reference. The main picture plane brings together the Virgin and Child, angels and saints in a unified space marked off by a patterned carpet. This unity is emphasised by the poses, gestures and positions of the figures, while the upper part of the altarpiece harks back to the tripartite divisions of a Gothic polyptych and is framed accordingly. As for the frame itself, Sassetta introduced a unique cassetta-type moulding which frames the bottom and continues to four-fifths up the sides to fit it into its shallow niche in the Duomo.

Upper panel of Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1433–35,

Tempera and gold on panel, 21.6×29.8 cm, Metropolitan Museum

In his Adoration of the Magi (c. 1435), a painting that was sadly cut in two, the upper part shows a concentrated attention to landscape we will see again in the Borgo San Sepolcro polyptych. The cavalcade depicted here is typical of the international Gothic courtly style reminiscent of Gentile da Fabriano, whose majestic Adoration of the Magi in Florence Sassetta may have seen there, and who he must have met when Gentile visited Siena. Everyone in Sassetta’s procession is decked out in the most extravagant contemporary court dress and the two magpies are, as are the two tall birds on the crown of the hill diagonally opposite, beautifully observed. Yet all this finery moves through a wonderfully still and sparse winter landscape, among bare trees. The riders, led by the star suspended against the white hill, pick their way along a path of bright stones and pass the pink gate of Jerusalem – unmistakably Siena’s Porta Camollia with the tower raising above.

Sassetta’s challenges

When Sassetta accepted the commission for the San Francesco altarpiece in Borgo, the challenge the painter faced was two-fold: not only was he facing the architectural constraints imposed by the wooden structure on the altar which, his contract stipulates, he was to follow, but he also needed to find a visual equivalent for the “poetics of Franciscan spirituality” (as Keith Christiansen called it) within the constraints of the iconographic programme.

Sassetta’s professionalism asserted itself immediately when he refused to accept the existing wooden structure and insisted on having a replica made in Siena where he would have the necessary facilities in his workshop. None of the documents relating to the altarpiece suggest substantial alterations of the 1426 structure which he must have followed closely. It is therefore the original carpenter who may be credited with combining two different traditional altar types: a tall gothic polyptych and a 13th century Umbrian vita-retable. For the front, as stipulated in the contract, Di Segna’s altarpiece was taken as a model while for the back possibly an earlier dossal format was adapted, an early version of which is still preserved in Assisi, consisting of double narrative tiers in each lateral panel so that biographical episodes flank the figure of Saint Francis.

The first, simple vita or dossal retables, were adapted to existing altar widths. It is the subsequent rapid growth in height, and therefore of overall size and width that required support systems such as buttresses anchored in the pavement at each side of an altar. The earliest example of a buttressed altarpiece, and also a prime example of a later complex dossal retable was extremely well-known to Sassetta: Duccio’s Maestà in Siena’s Duomo.

Buttresses were initially an architectural device, invented by gothic architects to permit them to construct buildings of soaring heights. In the same way the buttressed altarpiece permitted much loftier compositions. At the height of this development, the great gothic altarpiece essentially resembled gothic cathedrals. In the same way the internal structural organisation of the polyptych frame came to resemble church architecture itself. The most eloquent surviving example in stone of this phenomenon is the marble polyptych on the high altar of San Francesco, Bologna: a veritable church within a church.

Pierpaolo and Jacobello della Masegne, high altar, 1388-1392, marble, approx. 521 cm wide, San Francesco, Bologna

Sassetta who, as we have seen, was a master at adapting his style when a commission’s constraints demanded it, while harking back to revered older models, nevertheless asserted his “modernity” in the Borgo polyptych by adding Sienese refinement in its visual language and by applying richly gilded pastiglia (raised decorative patterns applied to wooden moldings) and polychromy to the framework. Emulating his great predecessors, Sassetta achieved a near-miraculous technical and artistic unity for his double-sided altarpiece, thereby rising triumphantly to the challenges of iconographic and structural constraint.

It is all the more deplorable that the frame for Sassetta’s double-sided altarpiece has suffered the fate of many altarpiece frames and has not survived. Reconstructions based upon the 1439 iconographic programme (the scripta) and the surviving twenty-seven (out of sixty) panels, give an indication of what it must have looked like in its mounted form on the altar of San Francesco. In the next post a closer look at the scripta and how Sassetta artistically interpreted the prescribed iconography as well as a discussion of some aspects of Sassetta’s painting technique.

Selected sources

- Enzo Carli: “Sassetta’s Borgo San Sepolcro Altarpiece”, The Burlington Magazine, 1951

- C. Gardner von Teuffel, “The Buttressed Altarpiece: a forgotten aspect of Tuscan fourteenth century altarpiece design”, Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen, 1979

- Keith Christiansen et al, Painting in Renaissance Siena: 1420-1500, exh. cat., Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988

- Henk van Os, Sienese Altarpieces 1215-1460, Groningen, 1988 and 1990

- Donal Cooper, “Franciscan Choir Enclosures and the Function of Double-Sided Altarpieces in Pre-Tridentine Umbria”, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 2001

- James Banker, The Culture of San Sepolcro during the Youth of Piero della Francesca, University of Michigan, 2003

- David Franklin, “A Contract Drawing for the Church of S. Francesco in Sansepolcro”, Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz, 2004

- Machtelt Israëls, Sassetta’s Madonna della Neve, Leiden, 2003

- Machtelt Israëls et al, Sassetta, the Borgo San Sepolcro Altapiece, The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies in Florence, Leiden, 2009