Last week the Rijksmuseum announced its acquisition of a painting by Haarlem painter Jan Jansz Mostaert (c. 1474-1552/53) entitled “Landscape with an Episode from the Conquest of America”, dated c. 1535 (oil on panel). An intriguing and somewhat puzzling work. How did it get its title? And what does it mean? Some questions to look into.

The painting, owned by the heirs of Jacques Goudstikker since it was restored to them in 2007, was shown at TEFAF. The asking sum was USD 14.3 million, but the Rijksmuseum, thanks to a cooperative art dealer and the generosity of the Goudstikker heirs, eventually closed the deal for a lesser, undisclosed, sum.

“A landscape in the West Indies”

As soon as the painting was discovered in a private collection in Scheveningen in 1909, it and its title became inseparable when it was identified as the work described by Mostaert’s biographer Karel van Mander in his “Schilder-Boeck” (Painter Book), published in 1604. Van Mander, the “Dutch Vasari” and also a Haarlem painter, had Mostaert’s grandson Nicolaes Suyker, a Haarlem burgher and art collector, as his informant. He showed the painting, which he owned, to van Mander, who describes it as

“… a landscape in the West Indies with many naked people, a jagged cliff, and strange construction of houses and huts, left unfinished.”

The identification of the scene as that of the conquest of America by the Spanish was perpetuated by a Spanish flag in the painting. This proved to be an overpainting and has been removed.

As far as we know, this is a one off work. Mostaert never signed or dated his paintings and his reconstructed oeuvre of some 50 paintings shows conventional religious works and several good portraits. Yet none of Mostaert’s other paintings mentioned by van Mander has been convincingly identified as any known work attributed to Mostaert today, solely this extraordinary painting, unique in early Netherlandish art.

A European style New World

If you stand in front of the painting, you find yourself drawn into a conventionally organised landscape that uses the standard three colour system of brown, green and blue for the chief zones of recession in space established by painters in Memling’s time and perfected by Joachim Patinir, works which Mostaert could have seen at the court of Margaret of Austria where he had worked as an artist. We also see echoes of these landscapes and of the “jagged cliff” in some other works attributed to Mostaert, for instance in the background of his “Portrait of a Lady”, also in the Rijksmuseum.

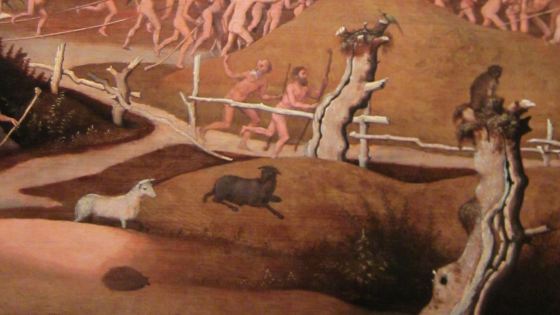

We are looking at the New World, but in our painting any sort of exotic foliage is missing and the animals depicted are low countries domestic cattle and wild animals (hare, rabbit, etc.). Only a porcupine, parrots and a monkey perched on a tree trunk provide exotic elements. It is possible that Mostaert saw these animals at Margaret of Austria’s court since he renders them more convincingly than some of his contemporaries did who had to revert to descriptions.

The story told by the painting is that of impending violence and the main action takes place on the middle ground where a military force, arriving by boats from the sea, is about to use canon on people with ineffective weapons. The inhabitants of the Arcadian landscape are all light-skinned, naked (except for a few men who appear to wear fur-lined caps) and some wear beards. By the mid-1520s there should have been sufficient information available for artists to be more precise about beards or lack of them, clothing or lack of it and the skin colour of the inhabitants. Clearly these people are not based on representations of New World inhabitants already known through prints, drawings and even from actual people brought to Europe and familiar to court artists.

The armed men in contemporary military dress wear costumes close enough to Netherlandish dress of the second and third decades of the 16th century, for instance in the short breeches of the figures on the path. Two women flee to the left, one with a child around her neck and holding another by the hand. This group leads the eye to a file of equally light-skinned nude men bearing weapons who run to resist the invaders as other men take aim with their longbows. Two other men are blowing long classical trumpets to rally more support. For us, with our hindsight, the outcome of the unequal battle that is about to unfold

A mysterious commission

Van Mander reports that, back in Haarlem, Mostaert received frequently visits by nobility, including members of the Golden Fleece. One of them could have commissioned the work. If he had died before the work was finished and therefore was unable to pay the artist, then this would explain why the painting remained in Haarlem and also why it was “left unfinished”. But at this point this is speculation.

Meaning

It almost seems as if the Old World’s reaction to the invaders’ cruelties against the natives of the New is implied in the painting. The first European indignation was relatively widespread in the second quarter of the 16th century, but in a more general sense the invaders could also embody man’s inherent savagery about to be inflicted on an ideal and peaceful society living in harmony with nature.

The emotional impact of the painting is all the more effective because Mostaert doesn’t show the carnage that will surely follow, but rather the pregnant moments immediately preceding it. If we wait just a little longer as the monkey with his face half turned towards us seems to tell us, we will be witnesses to the destruction, and by virtue of that, we will be implicated.