For over a century four gigantic paintings by the Amsterdam painter Ferdinand Bol (1616-1680) have hung in the Peace Palace in The Hague. Together with a fifth painting in the Provincial Executive of North Brabant they once formed an impressive series that hung in a town house in Utrecht. How they were originally hung and why there is no apparent thematic connection between them has long been a mystery. An intriguing question was who had commissioned such an ambitious and extravagant series of paintings? Recent research revealed many hitherto unknown facts, but has the mystery been solved completely?

The “Bolzaal” at the Peace Palace in The Hague

An unwelcome gift

In 1892 the paintings by Bol together with a painting by the Utrecht painter Jan van Bijlert were donated to the Dutch State by the Royaards family of Utrecht who wished the Bol series to be displayed in the Rijksmuseum. The museum must have received the gift with mixed feelings: not only were the paintings in Bol’s late Flemish manner and not considered his best but their size made it impossible for them to be displayed: all are over four meters high and even wider, the largest is almost five meters in width. By comparison Rembrandt’s Nightwatch is 363 cm high and 437 cm wide.

The house at Nieuwegracht 6, Utrecht

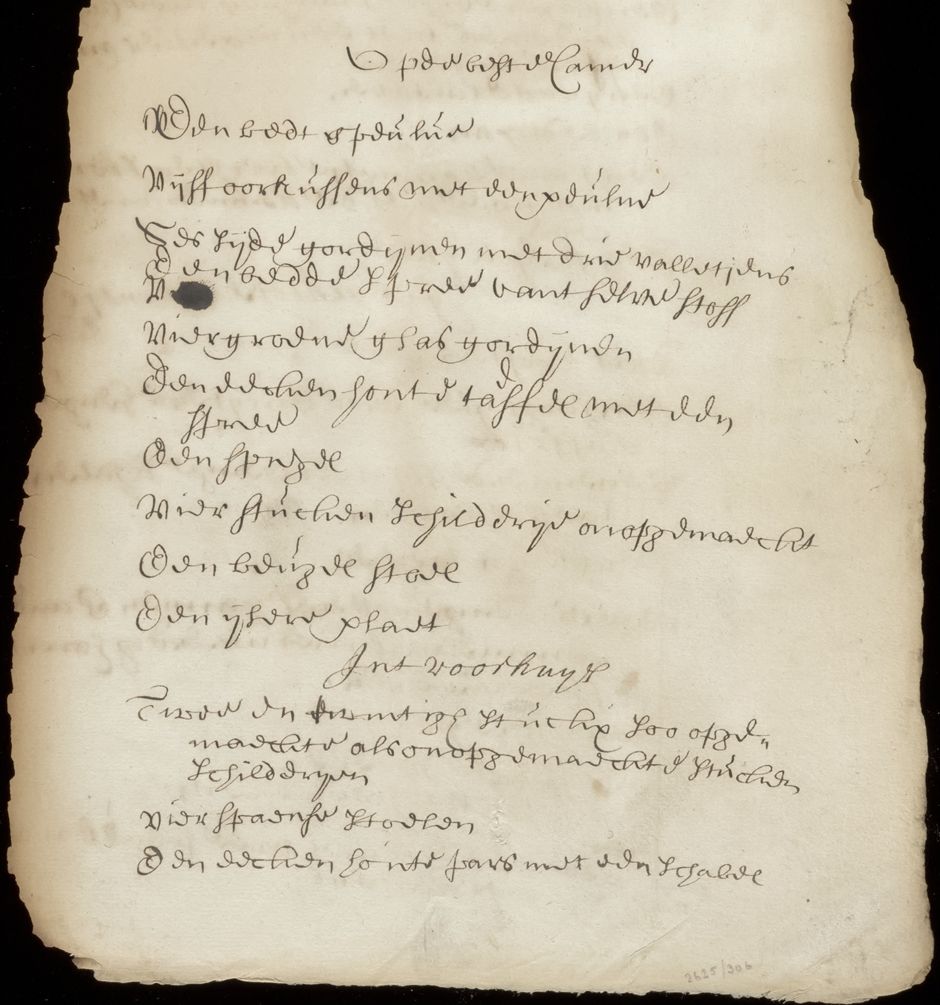

Until recently not much was known about the ensemble. Given their style, Bol’s paintings were dated between 1655 and 1669, the year he retired from painting. Old Rijksmuseum catalogues only mention that the paintings were “a series of wall coverings consisting of five large compositions by Bol from a room in the house at 6 Nieuwegracht in Utrecht”. What precisely that “room” was or how the paintings were hung remained a mystery until in 1982 an exchange of letters concerning the gift was discovered in the museum’s correspondence “Copyboek”. One of the letters records that the paintings were then in the “large back room”, the best room of the house, which was 10 meters long, 6.7 meters wide and 4.3 meters high. They were built into the panelling and covered the walls completely except for narrow strips of panelling between them. The detailed description of their location in the room helped form an idea about the order in which the paintings might have been hung originally.

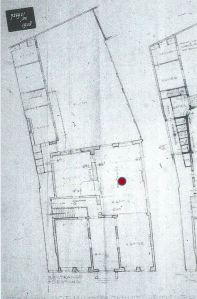

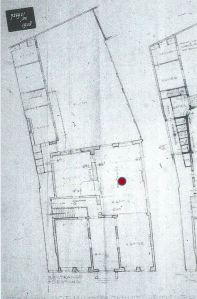

In Utrecht’s municipal archive an old ground-plan of the house was discovered which afforded an even better understanding of the room’s layout. It had three large windows facing east and overlooking the garden. The other walls had Bol’s paintings and the painting by Jan van Bijlert while the hearth was decorated with a painting by Utrecht artist Joost Cornelisz. Droochsloot.

Ground plan of Nieuwegracht 6. The red dot marks the room where the paintings hung. Municipal Archives, Utrecht

What paintings can tell us

Nail marks, remnants of varnish and of paint from the original frame

As luck would have it, various elements such as nail holes, remnants of old varnish and traces of paint from frames on the canvases were still intact; these are usually deemed unimportant by museum restorers and in most cases removed. Now that they were preserved they revealed how the canvases were stretched and framed. For example, vertical cuts were found which made it possible for the canvases to be slid between the ceiling’s beams. Today, the house is an office building and nothing of its original layout remains. The back part where the parlour was has been converted into an extension with an unattractive lowered ceiling but probes revealed that the 17th century beams with remnants of their original red paint are still present. Measurements confirmed that the cuts on the paintings fitted the distance between the beams exactly which provided vital clues about the order in which the paintings were hung originally.

Digital reconstruction of the west and north wall. From left to right: the Finding of Moses, Solomon Receiving Gifts, the Pool at Bethesda (mantlepiece), Venus and Adonis

Another aspect that was fairly unique was the discovery that the paintings had started life much smaller. Bol had enlarged them at a later time by sewing new strokes of canvas onto them. The Aenaes Receiving his Armour and Weapons, the first painting, had been conceived as a smaller painting that was extended at the top to its present height. Next, the Finding of Moses and Abraham Receiving the Three Angels were painted. Again these had begun as smaller canvases that achieved their present height through added strokes of canvas. In the third and last phase the series was completed with the The Lord Appearing to Joshua and Solomon Receiving Gifts. At that time both the Aenaes and the Moses were widened with a stroke of canvas of about one meter on the left.

Ferdinand Bol, Aenaes Receiving his Weapons and Armour, image Rijksmuseum

Jan van Bijlert’s Venus and Adonis which hung to the right of the hearth on the north wall has not survived intact. The painting had been given to the Centraal Museum in Utrecht where, during restoration in 1934, it was deemed beyond repair. The complete painting was photographed but only a fragment was preserved. The surviving portion bears such similarity to the style of Van Bijlert’s more famous townsman Van Honthorst that it was attributed to him; Van Bijlert’s signature on the discarded section of the painting had apparently been forgotten. Since the light in this painting comes from the left and given its position to the left of the windows it would seem that the Venus and Adonis were not specifically painted for the room unless, perhaps, the painting had been in the house prior to Bol’s interventions and had been rehung.

Jan van Bijlert, Venus and Adonis, 1934 photograph in the Centraal Museum

Jan van Bijlert, Venus and Adonis, remaining fragment, Centraal Museum

Sadly the original hearth with Droochsloot’s painting has not survived. It was transferred to the town hall of Soest after 1892 but was lost when the building was demolished around 1960. The last trace of the painting was a Utrecht exhibition in 1892. The catalogue states that the painting was signed and dated 1643 and gives its measurements but the painting’s current whereabouts are not known. Droochsloot painted several copies of The Pool at Bethesda, none of which, however, have the correct measurements.

The hearth from the back room at Nieuwegracht 6 before it was demolished. Photo municipal archives, Utrecht

Joost Cornelisz. Droochsloot, The Pool of Bethesda, copy in KMSKA, Antwerp

The commission

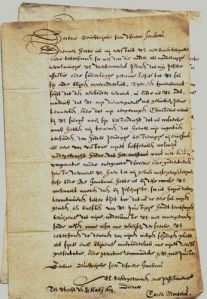

Love letter from Carel Martens to Jacoba Lampsins, Utrecht Municipal Archives

Since no correspondence or accounts regarding the commission have been preserved, the only way to find out who commissioned the series would be to determine who had lived in Nieuwegracht 6 in the late 1650s. Here, the municipal archives proved helpful. It turned out that the house had been sold in 1657 to a wealthy widow, Jacoba Lampsins, who had lost her husband Carel Martens eight years before. Martens, a wealthy lawyer and tax broker, had been a staunch Calvinist but also a passionate art collector. His ledger includes paintings by Ambrosius Boschaert, Joachim Wtewael and in 1645 “a figure in full” by Rembrandt. His wife continued to collect paintings after his death. Theirs must have been a very happy marriage: several love letters from Carel to Jacoba have survived.

Anonymous painter, Carel Martens, 1643, Centraal Museum

Anonymous painter, Jacoba Lampsins, 1643, Centraal Museum

Like her husband, Jacoba Lampsins was the daughter of an old and influential Calvinist family. Her ancestors belonged to the governing elite of Ostend in present day Belgium. She was born in the province of Zeeland where the family had moved to escape the violence and religious persecution of the catholic Spanish during the Eighty Years War. Given the status of her family it seems logical that Jacoba intended her three sons to climb the social ladder in Utrecht. Although a respected citizen and extremely wealthy thanks to the lucrative United East India Company shares owned by her family, more than mere money was needed to gain access to Utrecht’s upper crust, the regents, since important functions were limited to only a few of the ruling families. The only way for newcomers to become part of the elite was to marry into that circle.

Buying the town mansion on Nieuwegracht was the first step in that direction since this meant that Jacoba and her four children now lived among the wealthiest and most respectable burghers of Utrecht. She must have engaged Ferdinand Bol to decorate her parlour where she could receive distinguished guests in style and where she could present her three sons to their fullest advantage.

Digital reconstruction of the back room at Nieuwegracht 6. Left to right: The Lord Appearing to Joshua, Aenaeas Receiving his Armour and Weapons, Abraham Receiving the Three Angels and the Finding of Moses

Thematic unity?

At the time, ensembles of the magnitude of Bol’s could only be found in Amsterdam’s Town Hall and in the Sael van Oranje in Amalia van Solms’ palace at Huis ten Bosch in The Hague. There perfection was sought not only through the choice of painters but also by selecting subjects that were logically compatible and meaningful. At first sight, Jacoba’s paintings appeared to display no such unity or logic: for example the mythological Aeneas was wedged between two Old Testament scenes. It was therefore assumed that the paintings were not intended as a coherent ensemble and perhaps were even transported to the house on Nieuwegracht at a later time. The latter option seemed plausible: Ferdinand Bol painted almost exclusively for the Amsterdam elite and not for that of Utrecht. Cities reserved that right mostly for local artists.

Ferdinand Bol, The Finding of Moses, the largest paintings in the series. Bol was one of few painters who portrayed the women naked. Image Rijksmuseum

In a 1992 article the art historian Albert Blankert assumed that Bol had recycled the paintings he sold to Jacoba since the Solomon Receiving Gifts was a far larger version of another painting. Blankert even suggested that Bol may have sold her bits and pieces lying unfinished in his studio from commissions that had failed to materialise.

Ferdinand Bol or Rembrandt, sketch for the Finding of Moses, Rijksmuseum

An interesting theory that seemed to be supported by Bol’s drawing for The Finding of Moses which, judging from its Rembrandtesque style, was conceived much earlier than the painting. The drawing was in fact attributed to Rembrandt for many years. What may be in favour of Blankert’s theory is that all Bol’s paintings, as we have seen, started out as smaller versions and were extended to fit the room’s proportions. Researchers have now contradicted this and have sought to discover a thematic unity on the basis of what we know about Jacoba’s biography and the fate of her ancestors.

Ferdinand Bol, Abraham Receiving the Three Angels, image Rijksmuseum

As we have seen, the first painting in the series was the Aeneas and just like Aeneas, Jacoba’s and her husband’s families had had to flee their home. Crucial in this analogy is that Ostend, home to her ancestors, was at the time compared with Troy (it was even known as Nova Troja) because of the long siege and bloody conquest by the Spanish. The same analogy fits the Old Testament stories of Moses and Abraham who were forced to leave their native countries too and became symbols for Southern Netherlandish refugees. In addition, these three main protagonists were destined to become founders of influential dynasties and therefore epitomise Jacoba’s social ambitions for her sons.

Cyrus or Solomon?

Ferdinand Bol, Solomon Receiving Gifts (?). Image Rijksmuseum

During the last stages of the commission Jacoba added the Solomon and the Joshua. A possible explanation for these subjects, so researchers assume, could lie in a conflict between liberal and orthodox factions in Utrecht’s city council concerning the management of former catholic church goods. Any income generated from them was destined for charitable purposes but in practice the managerial tasks had fallen to a few wealthy families who used the profits for their own financial gain. Jacoba sided with the orthodox faction that advocated the return of the goods to the protestant church of Utrecht. This conflict, it has been argued, could be reflected in the story of Joshua: those who shamelessly enriched themselves could be compared with Achan who is guilty of plunder against God’s command. But Achan can barely be seen in Bol’s painting, if at all. The analogy must then have been by implication. In addition, the Solomon receiving gifts is now thought to depict King Cyrus who returned robbed temple treasures to the Jews. Since Bol painted a smaller version of this painting for Amsterdam’s Zuiderkerk, this would mean that such a highly unusual subject would be depicted there too. Has the painting been fitted to suit the theory?

Ferdinand Bol, the Lord Appears to Joshua. Image Rijksmuseum

Researchers have further suggested that Jacoba’s standpoint in the conflict may also have been inspired by the fact that one of the leaders of the orthodox faction, Johan van Nellesteijn, was the guardian of the extremely wealthy regent’s daughter Aletta Pater. Whether this was behind it or not, in 1663 Jacoba’s eldest son married Aletta. The marriage proved lucrative in many ways as through it he and his brothers secured honourable functions that continued for many generations.

Remaining questions

While many mysteries concerning Bol’s five paintings seem to have been resolved, there are some aspects that still depend on conjecture such as why the paintings, originally conceived as smaller works, would have been enlarged to fit the walls in Jacoba’s parlour. Would not Jacoba, had she commissioned them for that specific room, ordered the correct sizes to begin with? The identification of the subject in one of the paintings (Cyrus or Solomon) also needs further consideration. For now the Rijksmuseum sticks to the traditional title of Solomon Receiving Gifts. Another matter needing more research is Van Bijlert’s Venus and Adonis, the function of which, perhaps because of its sadly trunkated state, is as yet unclear. In spite of admirable and very sound research, I believe that, although very close, this intriguing case has not quite been cracked.

Van Eikema Hommes investigated various attributes such as the nail holes, old varnish remnants and paint remnants from frames on the canvasses. These revealed how the canvasses have been stretched and framed. For example, she found cuts which ensured that the canvasses could be pushed between ceiling beams. In a prominent house along a canal in Utrecht Van Eikema Hommes found the ceiling beams that fitted the canvasses. Further research revealed that the widow Jacoba Lampsins had resided in this house during Bol’s time. The canvasses formed a spectacular decoration that covered all the walls of a large reception room.Read more at:

http://phys.org/news/2012-02-true-history-ferdinand-bol-revealed.html#jCpDigital reconstruction with the original setting of Bol’s paintings in the reception room of Jacoba Lampsins in Utrecht. At the time, the paintings would be standing directly on the ground under the ceiling beams. In the 18th century, they were pushed up between the beams, to create space for panelling belowRead more at:

http://phys.org/news/2012-02-true-history-ferdinand-bol-revealed.html#jCpDigital reconstruction with the original setting of Bol’s paintings in the reception room of Jacoba Lampsins in Utrecht. At the time, the paintings would be standing directly on the ground under the ceiling beams. In the 18th century, they were pushed up between the beams, to create space for panelling belowRead more at:

http://phys.org/news/2012-02-true-history-ferdinand-bol-revealed.html#jCp