[Portrait painters] do not perhaps deserve much admiration because they concentrate all their efforts on a single part of the human body [the face]. Still, they have a noble and indispensable profession. I know no greater pleasure than to contemplate the painted facial characteristics of someone about whose life I have read or heard. It doesn’t matter to me if it concerns a good or a bad person. I can suffice by naming Michiel van Mierevelt, ‘facile princeps’ in this genre. (Constantijn Huygens)

Michiel Janszoon van Mierevelt of Delft’s life (1566-1641) roughly spans the Eighty Years War between Spain and the Low Countries. The city of Delft benefited from its proximity to the government headquarters of the Republic in The Hague. Moreover, when Stadtholder William of Orange moved to Delft’s Prinsenhof in 1582, Delft also became one of the court’s residences. In addition, the increasing wealth of the middle classes afforded great opportunities for a portrait specialist and from 1590 Van Mierevelt, the son of a goldsmith, devoted himself entirely to the art of portraiture.

Joachim von Sandrart wrote that Van Mierevelt “himself thought that he had produced some ten thousand likenesses”. Today’s estimate reduces this to a still impressive five thousand (of which some 629 survive), all showing a consistent quality in the careful reproduction of faces and the exquisite rendering of costumes and fabrics. Such quality and the high production rate of the studio could not have been achieved without standardised working methods and an efficiently run business.

Clients

Initially Van Mierevelt’s sitters consisted of the wealthy burghers of his native Delft, in particular members of the ruling regent families. His Delft clients remained a staple source of income throughout his long career. Soon, however, rich burghers and administrators from other cities of the Republic found their way to the Delft studio, mostly to sit for a single portrait or, with their wives, for pendants. Sometimes copies of these portraits were ordered so that a couple could present these to their children when they set up house for themselves.

Portraits were invariably executed on panel; only for the very few larger projects he studio executed (a militia company portrait and an anatomical lesson) Van Mierevelt resorted to canvas. From the onset the winckel offered standard formats: the portraits of burghers were mostly three-quarter lengths or half-lengths, copies were mostly busts. Only the nobility and the court commissioned full-length likenesses or conterfeytsels naer ‘t leven (likenesses from life). Standardised prices for the various formats did not change significantly over a period of thirty-five years; apparently Van Mierevelt did not feel the need to cash in on his success by increasing them:

- Full-lenght portrait: unknown; smaller format: 100 guilders; studio copy: 42-48 guilders

- Three-quarter length: 200-300 guilders (by comparison: a simple house in Delft cost circa 200 guilders); studio copy: 75-100 guilders

- Bust: 48-50 guilders; studio copy 24 guilders

A commercial coup

The Stadtholders were wealthy princes from the noble House of Orange. They had little political power but they were indispensable as army leaders and figureheads of the Revolt against Spain. In 1600 Prince Maurits of Orange, the Stadtholder at the time, won a military victory over the Spanish and the grateful States General ordered a suit of armour clad in gold-leaf to be made for the Prince. When in 1607, much against Maurits’ wishes, negotiations for a truce with the Spanish began, the Prince, almost as an act of defiance, commissioned Van Mierevelt (whose work he might have known from time spent at the family’s Delft residence) to portray him wearing his golden trophy harness.

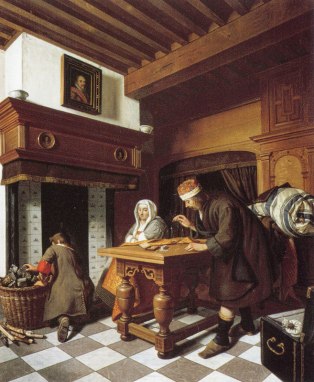

Sensing the commercial potential of the commission, Van Mierevelt immediately produced several copies of the Prince’s portrait in various formats, one of which he presented to the States General: a clever tactical move. It is estimated that Van Mierevelt and his studio produced over 100 copies of the portrait in various sizes which found their way to government institutions (where some of them still remain), the palaces of the Stadholders, the homes of the nobility, but which were also purchased by burghers as shown in Cornelis de Man’s The Goldweigher where a studio copy of the portrait can be seen hanging over the mantlepiece.

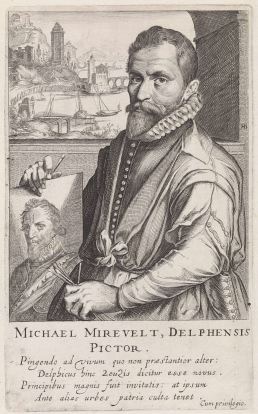

In another clever commercial move Van Mierevelt authorised Delft engraver Jan Mulder to make an etching of the Prince’s portrait and in 1607 the States General granted the patent for its exclusive reproduction rights for a period of six years to the painter. Anyone copying the portrait would incur a fine of 100 guilders, a considerable sum at the time. Three years later Van Mierevelt proudly had himself depicted while holding a copy of his greatest commercial success, the etching by Simon Frisius was possibly made after a now lost self-portrait. Etchings could be quickly multiplied and served the less affluent in the Republic: there was a lucrative market for images of “people in the news” at a time when mass media still had to be invented.

Fame

The Prince’s portrait and its many copies which would have been encountered everywhere attracted the court and the higher nobility to Van Mierevelt’s studio and in their wake the intellectual elite and political figureheads of the Republic.

Amalia van Solms, wife of Stadtholder Frederick Hendrick and mother of the future William I of England, ca. 1634, Haags Historisch Museum

Foreign diplomats and army leaders, too, found their way to Delft to be portrayed. This was greatly helped by the fact that the Republic’s center of power lay in The Hague, not far from Delft, so that foreign ambassadors and visiting military leaders, before departing for home, made a stop in Delft to have their likeness immortalised. It was not uncommon for them to order several copies to give to friends and relatives, which contributed to Van Mierevelt’s fame spreading to the surrounding countries and especially England. English armies fought on the side of the Republic and their generals and English diplomats, mostly aristocrats, would sometimes spend years in the Low Countries.

Horace Vere, Baron Vere of Tilbury, ca. 1629, National Portrait Gallery. An unusual portrait among the works by Van Mierevelt for the addition of an army camp at the bottom

Three times Van Mierevelt rejected prestigious offers to become court-painter, twice by English rulers (Prince Henry and Charles I) but he was not going to abandon financial stability for a prestigious but uncertain career in a foreign country. The most Prince Henry could extract from him was a promise to come to London for a three-month period but even that came to nothing.

The political, diplomatic, court and intellectual circles were close-knit and word of mouth brought Van Mierevelt more clientele than he could handle even though at any one time three or four fully trained assistants were working with him in the winckel. Assistants would produce the copies and, while the master always painted the faces himself, often worked on the hands and costumes of the original likenesses. Among them were the master’s two sons Jan and Pieter (both would die young) and later his grandson Jacob, the son of his preferred engraver Willem Delff and his daughter Geertgen. Other assistants such as Paulus Moreelse later went on to have successful careers of their own.

Standardised methods

In Van Mierevelt’s entire oeuvre facial measurements and proportions were consistent, so much so that it appears that he used a prototype for both male and female faces although he would adjust this prototype for each client in such a way that the portrait bore a good resemblance.

Copying techniques were also standardised: research has revealed perforation tracings but also the use of painted red lines setting out eyes and contours. It is not quite clear how this was used in copying but a possibility could be that underneath these red lines a chalk outline was present applied by means of a perforation drawing or tracing. In the portrait of the “Winter King” Frederick V horizontal lines have been found at regular interval indicating that pieces of string were stretched across the panel to transfer the composition to another panel to make the compositions identical.

Copying techniques were also standardised: research has revealed perforation tracings but also the use of painted red lines setting out eyes and contours. It is not quite clear how this was used in copying but a possibility could be that underneath these red lines a chalk outline was present applied by means of a perforation drawing or tracing. In the portrait of the “Winter King” Frederick V horizontal lines have been found at regular interval indicating that pieces of string were stretched across the panel to transfer the composition to another panel to make the compositions identical.

Efficiency was another hallmark of Van Mierevelt’s studio: the layers of paints were used as economically as possible. Coloured paint in the underpainting was intentionally left visible in the upper layers. Along the contours of the eyelids red lines of the underpainting can often still be seen.

Appreciation

Van Mierevelt has been criticised for the uniform, almost monotonous style of his portraits: men are invariably turned to the right, women to the left, also when they were stand alone figures and not companion husband and wife portraits. The standardised facial prototypes generate great similarity between faces throughout the painter’s career – proportions, too, are alike between male and female faces: distances between the outer edges of the eyes, jawlines and proportional distances between eyes, noses and mouths were remarkable similar, regardless of the specific individual sitters’ facial type. We notice this today due to the advantages of photography and the Internet which facilitates comparisons. In his own time, however, van Mierevelt was invariably highly regarded by his clients and the standardisation had an additional benefit: clients usually only had to pose only twice for the master.

Michiel van Mierevelt, Constantijn Huygens, 1641, Huygens Museum, Voorburg. Huygens wrote that the portrait was painted with the painter’s “dying hand”

Because so many famous Dutch writers and poets sat for the master, we have a remarkable number of contemporary ego documents regarding his personality and his comfortable studio. To quote Constantijn Huygens again (he sat twice for Van Mierevelt):

No one has ever been able to determine that he was anything other than himself, that he lost sight of his goal, that he, as it is called, deviated from his path. With Van Mierevelt art is on a par with nature and all nature is encompassed within his art. He seeks truth and because the outer appearance of truth is, in essence, simple, he finds it because he respects it and safeguards it from all things strange. At the same time his own input as an artist is of the highest caliber. Especially the softness of the flesh, so rarely depicted, is painted by him with the utmost accuracy. If you study the way he conducts himself, you will see that the way in which he paints is mirrored in his behaviour. If treating difficult subjects, his behaviour, his attitude and his words are simple. He deliberately hides behind a mask of ignorance and therefore makes things rather awkward for experts.

But Huygens, writing towards the end of the master’s life, also noticed a decline in his work, something the master himself was not blind to (“he admires rather than experiences the work he made at the peak of his powers”):

(…) but even now that his strength subsides he proves how superior he still is over painters of all centuries. I can wish for nothing better than that we may have him among us for a long time to come even now that he has outlived his fame and his talents. I consider it a great honour to belong to his closest friends.

From 1637 onwards, the court, led by Amalia van Solms, had transferred its favours to an upcoming painter from Utrecht, Gerard van Honthorst and in the court’s wake the intellectual elite followed. For the old master this may have come at a good time. He had amassed a fortune which he had invested prudently, yet he kept on working. When he died, on 27 June 1641, he left many paintings in his winckel that had still to be finished and it was his grandson Jacob, who was trained by him and who lived with him in his final years, who completed them.

One of his last portraits must have been this self-portrait, showing him painting his grandson. His painter’s cap is draped over the easel as if he is symbolically appointing his successor.

Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt, self-portrait painting his grandson Jacob Delff, c. 1641, Private Collection

Notes:

- Information about Michiel van Mierevelt’s studio practice is derived from the 84 page inventory, drawn up two month’s after the painter’s death and available online and from research conducted into several portraits on the occasion of the Van Mierevelt exhibition in Delft, 2011, published by the Prinsenhof Museum.

- Quotations from Constantijn Huygens are from the part of his unpublished autobiography in Latin, De vita propria sermonum inter liberos (1677) translated in Dutch by C.L. Heesakkers and published as Mijn Jeugd (My Childhood) in 1987.

- Today, portraits from Van Mierevelt’s winckel can still regularly be found on the art market. See for instance this selection from Christie’s, which includes an attractive bust copy of the Prince Maurits portrait.