Michael Sweerts’ life is shrouded in an infrequently interrupted silence. Documentary evidence is scarce and he left no letters or even signed documents that we know of. We catch glimpses of him in Brussels, Rome, Amsterdam, Marseilles, Persia and finally Goa but he must have traveled more than this for it is recorded that he spoke seven languages. A fragmentary life can be reconstructed to some degree, but the gaps have given rise to speculations about Sweerts’ character: a religious fanatic, a homosexual, a loner, a “tormented soul”. How are we to interpret the few archival documents and do his paintings provide any clues?

The mysteries start early: we know that Michael Sweerts was baptised in the catholic church of St Nicholas in Brussels as the son of David Sweerts, a merchant, and Martynken Balliel on 29 September 1618. Other than that, nothing is known about his early years or about his artistic training and as far as I know no paintings from his early Brussels years survive.

Rome: Cavaliere Sweerts

It is not until 1646 that we catch up with him. Michael Sweerts, 28 year old, is recorded as living in the parish of Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome in Via Margutta where he shared lodgings with several other Northerners. A colourful neighbourhood where artists, prostitutes, beggars and foreigners mingled. In that same year, he is also recorded in the archives of the Accademia di San Luca, the painter’s academy, as being charged with collecting contributions for the feast of St Luke from other Northern artists living in Rome.

No documents survive to prove that Sweerts was either a member of the Bamboccianti, a group of Northern painters living in Rome, or of the Accademia di San Luca (the painters’ academy) but to conclude that Sweerts was therefore a loner or that his apparent involvement with both movements, one concentrating on “low subjects”, the other on elevated ideals, means that as a painter and as a person Sweerts was conflicted has no foundation.

On the contrary, far from being a loner and a sad figure, Sweerts had an important patron in Rome: Prince Camillo Pamphilj (1622-66), a nephew of Pope Innocent X, who renounced his cardinalate to marry the woman he loved in the year when Sweerts is first recorded in Rome. Camillo owned at least four paintings by Sweerts and his accounts show that the artist also painted theatrical decors for him and served as his agent in purchasing art. It was presumably Camillo who secured a papal knighthood for the painter who is referred to in several contemporary documents as”Cavaliere Sweerts”.

It is not inconceivable that Sweerts painted Plague in an Ancient City (1650) for Camillo. It is his most ambitious classical work and it is heavily indebted to Nicholas Poussin’s Plague at Ashdod (ca. 1630-1) which he could have seen in Rome. Unlike the intellectual Poussin, Sweerts did not have a specific plague in mind. Rome at the time was suffering under a financial depression, frequent plague epidemics and famine. In his Plague in an Ancient City, Sweerts depicts these very real horrors within a timeless classical setting. If one realises that a particularly fierce plague epidemic struck Rome while Sweerts lived there and that there was a chronic shortage of bread, the staple food of the poor, it becomes easier to understand the compassion so apparent in Sweerts’ paintings.

Rome: Northern patrons

In Rome, Sweerts also attracted wealthy Northern clients. Some of these were spending part of their Grand Tour there, some were there for trade and some, like three of the five Deutz brothers from Amsterdam, were in Rome for both purposes. Not only did Sweerts paint for the brothers, but he also acted as their agent in purchasing and shipping paintings, frames and classical sculptures while a 1651 power of attorney shows that Jean Deutz employed Sweerts in connection with a shipment of silk.

Joseph Deutz, whose unconventional portrait Sweerts painted in Rome, seems to have been Sweerts’ greatest admirer among the brothers. In his house on Herengracht (today no. 450) a considerable number of paintings by Michael Sweerts hung in the grand “purple drawing-room”, among which a series depicting the Seven Acts of Mercy, which included Feeding the Hungry (above) and Clothing the Naked (below).

For me, the Seven Acts of Mercy series (ca. 1646-9) represents most of what Sweerts stands for: the silence, the frozen movement almost like a film still, the dreamlike setting with its beautiful skies, the compassion and empathy with the subjects’ suffering and the charitable acts performed on them with which Sweerts seems to have identified. They are among his most moving works.

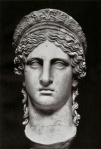

Far from being a depressed loner then, Michael Sweerts seems to have had a varied and successful career in Rome and even a following for various early copies of his Roman paintings survive. That his painting of a Roman wrestling match as well as later paintings of young men bathing show that Sweerts was a homosexual and added proof of his “inner turmoil” is, I believe, a misconception. Until the 19th century it was unacceptable for women to be painted nude outside of the context of a mythological setting. For men it was different. One cannot exclude homosexuality, but one cannot exclude heterosexuality either – there simply isn’t any concrete evidence. Instead, the paintings of nude young men show Sweerts’ preoccupation with classical Roman sculpture that we already noticed in my previous post.

Far from being a depressed loner then, Michael Sweerts seems to have had a varied and successful career in Rome and even a following for various early copies of his Roman paintings survive. That his painting of a Roman wrestling match as well as later paintings of young men bathing show that Sweerts was a homosexual and added proof of his “inner turmoil” is, I believe, a misconception. Until the 19th century it was unacceptable for women to be painted nude outside of the context of a mythological setting. For men it was different. One cannot exclude homosexuality, but one cannot exclude heterosexuality either – there simply isn’t any concrete evidence. Instead, the paintings of nude young men show Sweerts’ preoccupation with classical Roman sculpture that we already noticed in my previous post.

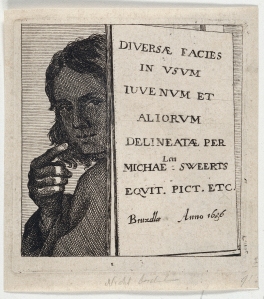

Brussels – the Sweerts Academy

By July 1655 Michael Sweerts was back in Brussels but why he left Rome is unclear. A letter to the Brussels authorities written on 26 February 1656 by Willem van der Borcht, a notary public and playwright, requests the exemption of certain taxes for “Cavaliere Sweerts” on the grounds that the painter founded an “academy of drawing”. The purpose of this academy, so the letter tells us, was to train tapestry designers with the aim to restore tapestry manufacturing “to its old lustre”. For his academy Michael Sweerts produced a limited series of etchings of heads for the benefit of “the young and others”. The etchings may have had a dual purpose: not only did they serve as models for the academy’s students, but because they were cheap and easy to reproduce they would have served as advertisements of Sweerts’ art. Several are etchings after (details of) his own paintings. The theme of education and training seems another recurrent one in Sweerts’ life: his academy but also several artist’s studios that he painted over the years testify to this.

In the north, Sweerts’ painting style changed. It became softer, more lyrical and achieved a felicitous compromise between realism and idealism, most apparent in several enchanting portraits of young boys. These all follow a similar pattern: the boys turn their heads sideways, looking at something outside of the painting. Again, Sweerts’ approach is different from that of most of his contemporaries: he never patronises his young models. They are neither dressed up dolls nor miniature adults but they are portrayed sympathetically and with respect for their personalities. The most charming of these portraits is that of a young boy painted ca. 1655-6.

Amsterdam and beyond

Did Michael Sweerts leave Brussels because his academy was a failure? Again, there is no proof of this. Rather, he seems to have felt attracted to the Société des Missions Etrangères, a lay religious movement that solicited members for missions to the Far East in 1659 and 1660. Sweerts was selected for a mission to China. His farewell from Brussels seems determined and definite, he seems to have been committed to this new life for he gave the painters guild of St Luke a self-portrait “to remember him by” as the guild records specify. Most likely it is this self-confident, proud depiction of himself as a painter which gives no hint of failure: quite the contrary.

Sweerts moved to Amsterdam, where he is recorded living in July 1661, ostensibly to assist another lay member of the Société in supervising the construction of the missionaries’ ship. Here he probably reacquainted himself with the Deutz family: he painted at least the portrait of Gideon Deutz while living in the city.

Around this time we catch the first glimpses of what has been called Sweerts’ “religious fanaticism”. In diaries kept by missionary Nicholas Etienne we find descriptions of Sweerts visiting the churches and the poor of Amsterdam. He is fasting, sleeping on a hard floor and many “beautiful secrets” are communicated to him “from the cross”. But this kind of behaviour was very much in keeping with the religious devotion the movement was interested in propagating and the account may have been exaggerated. While there is no doubt that Sweerts took the mission very seriously he seems not only to have been selected for the mission on account of his religious fervour but also because he was “knowledgeable in some excellent art such as (…) painting” as the 1659 tract phrases it.

The mission, consisting of seven priests, two lay brothers and their leader Bishop Pallu, set sail for Palestine on the first leg of the journey to China on 2 January 1662. The journey was a hazardous and difficult one: four mission members died. It seems to have been on board ship that Sweerts started to display erratic behaviour. He became argumentative and difficult to handle and in the end Bishop Pallu decided to dismiss him, telling him that his “painting could indeed be of service” but that his “actions interfered with the general wellbeing”. Pallu writes from Tabriz in Persia in July 1662:

“Our good Mr Svers is not the master of his own mind. I do not think that the mission was the right place for him, nor he the right man for the mission. (…) Everything has been terminated in an amiable fashion on both sides.”

And so Michael Sweerts and the missionaries parted company.

Whatever may have occurred, Sweerts continued to paint on the journey east. He painted a portrait of Bishop Pallu (now lost) in Marseilles which Pallu thought “admirably well done”. A curious small panel, just 21.7×17.8 cm, is thought to have been painted in Persia, although the costumes in part seem to be fantasy ones. Could these men be members of the expedition and is the man in red leaning on the railing of their ship?

None of Sweerts’ religious paintings have survived, although several are mentioned in contemporary inventories. Sweerts himself made an etching after his painting of a Lamentation which is unusual for the Virgin’s comforting gesture towards the inconsolable Mary Magdalene. But religion is a multi-faceted concept. What to think of the Seven Acts of Mercy, based, after all, on Matthew XXV: 35-36. Or what to think of an enigmatic and haunting painting in the Metropolitan Museum, now entitled Clothing the Naked but with unmistakable New Testament overtones?

After Pallu’s intervention in whatever conflicts had arisen, Sweerts traveled on to Goa on the Indian peninsula alone, possibly to join the Portuguese Jesuits there. The Société records that he died there in 1664, at the early age of 46. The cause of his death is not given.

A life shrouded in silence and mystery

We leave Michael Sweerts for now with a painting of a man with a skull, thought to be a self-portrait. When Alfred Bader acquired the painting in 1968, the skull had been painted out. A previous owner obviously thought it too crude, but the skull’s omission left the man’s pointing finger without aim or purpose. This is a theatrical painting and although it was not unusual for 17th century painters to portray themselves with a skull, Sweerts takes it a step further: the man does not only point at it but inserts his finger in the nasal cavity, giving the painting a dramatic tension and mystery that lends an unusual twist to such a time-honoured vanitas symbol.

Michael Sweerts looks straight at us while he emphatically draws our attention to the skull. We are torn between it and his intense gaze. It makes us feel somewhat uncomfortable but at the same time it intrigues and pulls us irrevocably into the painting. He opens his mouth as if to speak to us but we hear no sound. Here, as in his life, Sweerts’ silent world is in the mystery that we are left to interpret by ourselves.

Notes:

- All works by Michael Sweerts unless stated otherwise.

- The Bamboccianti group of Northern painters in Rome were named after the nickname of one of the leading figures, Pieter van Laer. He was called Bamboccio, which meant something like “ugly puppet”. In Dutch they were called the Bentvueghels, which is a 17th century expression meaning “birds of a feather”.

- I am indebted to J. Bikker’s article on Michael Sweerts and the Deutz brothers in Simiolus, XXVI, 1998, to I.H. van Eeghen’s Amsterdam archival research published in Amstelodamum (several articles dating 1960 through 1975) and to the 1958 and 2002 Catalogues of the Michael Sweerts exhibitions held in Rotterdam and Amsterdam respectively.