A riddle

If his estimated year of birth is correct, Jacob Cornelisz was twenty-five or thirty when he purchased his house on Amsterdam’s prestigious Kalverstraat in 1500. Yet the first surviving prints and paintings from his studio are dated 1507. What had made the artist so affluent and apparently so successful in spite of any lack of extant work prior to this date?

A clue could lie in the extraordinary accomplished ornamental and architectural borders on his prints (see e.g. fig. 1). While in paintings the artist’s handling remained fairly conservative throughout his career, it was in his prints that he became a pioneer, abandoning the late Gothic style for innovative elaborate Renaissance frames fairly early on. Their sculptural handling, incised into the woodblock, may point to carvings on choir stalls or sculptural altarpieces.

Apart from the main parochial churches, the Old and New Church and the Miracle Chapel, one should not forget that late medieval Amsterdam was home to no less than twenty-one religious establishments as well as a number of religious guesthouses for pilgrims, each with their own chapel requiring decorations. Today, practically none of these survive and if they do they have been so much altered over time that hardly any of their original decorations survive.

The choirs stalls of the Old Church (fig. 2), Jacob Cornelisz’ parish church, date from around the year 1500 and the surviving reredos, though mostly damaged, give an impression of what these carvings would have looked like. Because tools used in woodcarving and woodblock cutting are the same (chisels, gouges and knives), it is not inconceivable that Jacob Cornelisz started his career as a three-dimensional woodcarver or even that, like his more famous contemporaries Dürer and Lucas van Leyden, had been trained as a metal worker. While he did not sign any of his paintings prior to 1523, his woodcuts – just like the prints by Van Leyden and Dürer – consistently bear his mark, a practice most likely adopted from the world of precious metals (for an explanation of the mark, see here).

Innovative printmaker

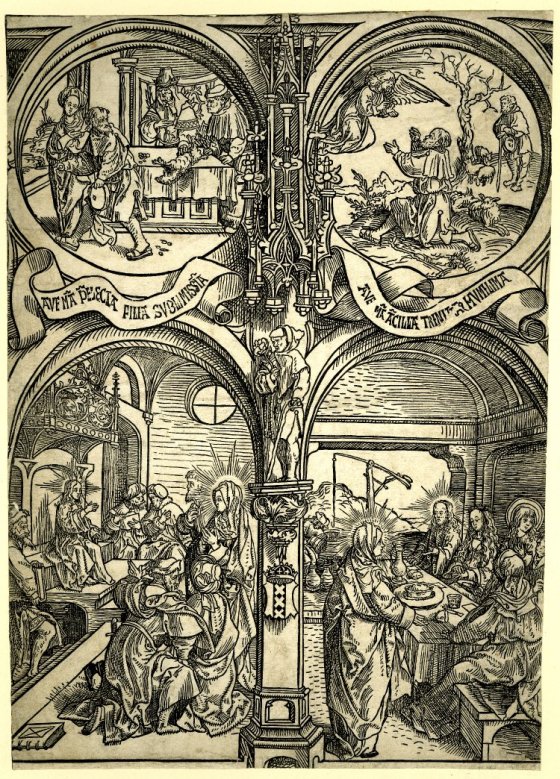

While Dürer and Van Leyden worked both in woodcuts and in the relatively new technique of engraving, Jacob Cornelisz stuck to woodcuts throughout his career but within that genre he is unique in his production of series of large multi-block prints consisting of several smaller sheets of woodcuts. His first surviving printed series, the Life of the Virgin Mary (1507) (fig. 3), for instance, was made from seven woodblocks, the sections of which were pasted together to form a frieze stretching almost two metres in width.

3. Life of the Virgin plate 1: Gothic ornamental framework inset with two arched scenes below and two roundels above; lower left, Christ among the doctors; lower right, Wedding of Canaan; top left, Joachim’s sacrifice being refused; top right, the angel of the Annunciation appearing to Joachim, 35×24.8 cm, British Museum

Series like these were made to adorn the walls of town houses, monasteries and convents, fraternities, hospitals and perhaps schools and would be hung or pinned onto walls unframed which explains why few have survived: after a number of years they would have been worn and torn and simply thrown out.

From the outset of his printing career, Jacob Cornelisz as well as his slightly younger Leiden colleague Lucas van Leyden, appear to have competed artistically with the most influential printmaker of the day: Albrecht Dürer of Nuremberg in Germany, yet their approaches were very different as illustrated, for instance, in their renditions of the Betrayal of Judas (figs. 4 and 5).

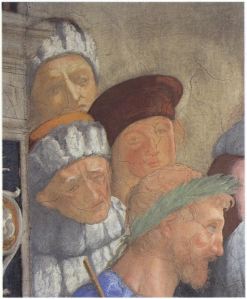

While Jacob Cornelisz’ version (from his Large Round Passion series, ca. 1511-14) is based on Van Leyden’s Round Passion of 1509 in which the latter’s characteristic delicate handling and serenity prevail, Jacob Cornelisz depicts a dramatic and lively scene in a rather compressed, crowded composition, at the same time demonstrating his great love for characteristic heads also apparent in his paintings.

A fruitful collaboration

A number of the woodblocks for the Life of the Virgin of 1507 were reused in 1513 by the Amsterdam printer and publisher Doen Pietersz (ca. 1480-after 1536). Earlier scenes were cut from the woodblocks and expanded by Jacob Cornelisz to form a series of The Seven Sorrows of the Virgin Mary, complete with newly cut elaborate renaissance-style borders printed from a separate woodblock. We do not know when exactly the collaboration between publisher and artist began but they were to work intensively together throughout their careers.

6. Address and monogram of publisher Doen Pietersz (“Dodo Petrus”) from the “Credo”, 1520, 15×12.5 cm, Rijksmuseum

Jacob Cornelisz’ prominent and consistent mark on the woodcuts, however, probably means that he played a dominant role in the production process and guaranteed the quality of the prints. Pietersz would have been responsible for the administrative side of things: applying for privileges, contracts and arranging distribution. In 1516 Pietersz obtained the imperial privilege, intended to protect his books and prints from copyists, a privilege mentioned on Jacob Cornelisz’ reissued Round Passion of 1517 and the series of the Counts and Countesses of Holland (fig. 8). For the latter series, Jacob Cornelisz devised imaginary portraits such as he would have known from the wooden statues adorning the Tribunal of Amsterdam’s Old City Hall close to his home and workshop (fig. 7).

On 30 April 1520 Pieterz agreed a contract with the representative of the Archbishop of the Danish city of Drontheim to print a “prayer book of the passion of our Lord” in an edition of 1200 copies. Interestingly, Jacob Cornelisz appears as witness together with Pompeius Occo, the merchant and humanist we encountered in the previous post. Because of the untimely death of the Danish representative the book never materialised, but the event proves that Pietersz operated on an international scale and was also well acquainted with the influential Amsterdam intellectual elite of his day. Never one to waste good material, Pietersz went on to publish what may have been Jacob Cornelisz’ series for the aborted Danish prayerbook supplemented with a series of the Twelve Sybils by Lucas van Leyden in 1521-23 (fig. 9).

9. Sheet 6 from Scenes from the Life of Christ, Sybils, Virtues and Vices, by Jacob Cornelisz and Lucas van Leyden, 1521-23, 37.5x26cm, Rijksmuseum

In addition, in 1523 Jacob Cornelisz’ Small Passion appeared in book form under the title Passio Domini Nostri, originally consisting of sixty-two woodcuts, later expanded with eighteen more. The book was commissioned by Pompeius Occo and contained Latin texts written by the scholar Alardus van Amsterdam: a fine example of the close relationships between a small circle of intellectuals in Amsterdam. Indeed, Occo’s house on Kalverstraat, not far from Jacob Cornelisz’ workshop, contained a considerable library and was a regular meeting place for humanists such as Alardus van Amsterdam. It is not unthinkable that Jacob Cornelisz and his publisher Doen Pietersz were frequent guests there too. Some of the woodcuts, such as Christ on Mount Olive in the Passio Domini Nostri (fig. 11) are of an exceptional artistic quality. For Alardus van Amsterdam Doen Pietersz also published the pamphlet Ritus Egendi Paschalis Agni for which Jacob Cornelisz supplied three woodcuts (fig. 10).

Workshop participation

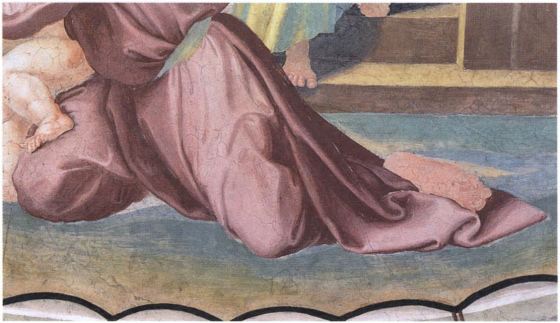

Although there is no documentary evidence, it appears from discrepancies in the quality of the woodcuts that Jacob Cornelisz did not personally carve them all. While, for instance, in the Carrying of the Cross from the Life of the Virgin series (fig. 12) the draperies and the plants in the foreground have been beautifully cut, those in the same scene from the Large Round Passion (fig. 13) seem far more mechanical and less inspired. No doubt the Master entrusted a proportion of the work to collaborators (among whom his two sons and perhaps also his two daughters) in the workshop. The Master’s mark nevertheless guaranteed the quality of the prints.

International recognition

As we have seen, Jacob Cornelisz’ prints were first and foremost utilitarian in character. His large religious and educational ensembles were meant to hang on people’s walls and smaller prints, sold as souvenirs to pilgrims to the Miracle Chapel for instance, have rarely survived, unlike the prints of Lucas van Leyden which were eagerly collected. This does not mean, however, that Jacob Cornelisz’ prints were not internationally appreciated judging from the publication of some of his prints by Brussels publisher Joannes Mommart as early as 1513.

A unique document in this respect is the detailed 16th century inventory of the Spanish print collection of Ferdinand Columbus (1488-1539), second son of the explorer (fig. 14). Ferdinand’s private library in Seville contained 15,000 books and 3,204 prints and was one of the largest in Europe at the time. The print collection is now lost but the inventory tells us that Ferdinand owned a considerable number of Jacob Cornelisz’ prints, although he may not have been aware of the identity of the artist since he only knew him by his enigmatic monogram. The document is extremely useful for the reconstruction of print series that have not survived or survived incomplete such as the impressive series of the Holy Knights (1510) (fig. 15). Of this series Ferdinand possessed both the individual prints and copies mounted on scrolls which, the inventory states, originally comprising seven prints of which today only five survive.

15. The most impressive of the Holy Knights: the Archangel Michael defeating a dragon. Also note the fine caligraphy and the Master’s mark on the rock on the left, 1510, 38.2×25 cm, Rijksmuseum

Ferdinand’s collection, the inventory tells us, also contained the complete series of Fourteen Prophets from the Old Testament, produced as an extension of a Credo series published by Pietersz in 1520 (fig. 6). The Credo has only survived in a few fragments and of the fourteen Prophets today only five survive with their borders incomplete, but what a delightful series it is! While the ornate ornamental borders demonstrate Jacob Cornelisz’ inventiveness as a designer, the imaginary Prophets themselves are even more attractive, demonstrating the artist’s love of characteristic heads to its full advantage. The corpulent Prophet Hosea (fig. 17), in profile, reminds of the (also imaginary) portrait of Count Floris II, nicknamed “the Fat”, from the Counts and Countesses of Holland series (fig. 16) while the African Prophet Amos (fig. 18) testifies to the early presence of foreign visitors in Amsterdam. But undoubtedly the most appealing portrait is that of cross-eyed Joel with his wild hair, tall hat and almost cartoon-like wrinkled face (fig. 19).

Vaults

20. The Last Judgment, Alkmaar, St Lawrence Church, painting on wooden choir vault, ca. 1516-19. Photo: Hans Verbeek

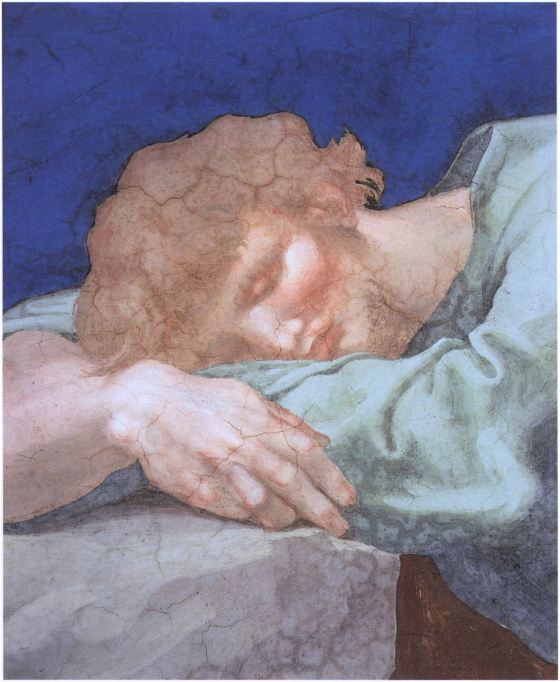

The gigantic Last Judgment high up in the wooden vault of St Lawrence Church in Alkmaar (figs 20-22) consist of nine compartments. The paintings in the choir vault bear the date 1518; they were part of an extensive refurbishment of the church which had begun in 1470 and was completed in 1519. While a payment to Jacob Cornelsz’ brother, the painter Cornelis Buys, who lived close to the church, survives in the Alkmaar archives, the recent restoration of the paintings has confirmed the authorship of Jacob Cornelis. Obviously, he could not have carried out such an extensive and ambitious project on his own: his brother and both workshops would have been assisted.

In the nearby village of Warmenhuizen (fig. 23) a similar vault, also depicting the Last Judgment has survived, thought to have been executed circa 1525. A third vault, in the North Holland city of Hoorn, was overpainted in 1771 and finally perished in an 1838 fire.

Towards the end of the 19th century the vaults in Warmenhuizen and Alkmaar were dismantled because of their deplorable condition and transported to the Rijksmuseum where they underwent invasive restorations. According to then prevailing restoration ethics, much was overpainted in the style and taste of that time. Eventually they were moved back to their original locations: the Alkmaar vault in 1925 (but due to lack of funds the vault could only be placed back in 1941) and the vault in Warmenhuizen in the 1960s. As late as 1999 the Alkmaar transept paintings, deemed lost, were discovered by chance in the Rijksmuseum depots. All have since been restored, the most invasive 19th century overpaintings removed, and can now be admired once again in situ.

23. The Last Judgment, ca. 1525, St Ursula Church, Warmenhuizen, detail: an angel conducts the blessed souls to heaven

Another surviving ensemble are the choir vault paintings in Naarden’s Great Church (presumably finished in 1518) (fig. 24) which were not executed by Jacob Cornelisz and his workshop but were based, in part, on his prints, in particular on his Large Round Passion of circa 1511-1514, reissued in 1517. For example, Naarden’s Betrayal of Christ is based on the same scene in the Large Round Passion series (see fig. 5).

Designs for liturgical vestments and stained glass

Roundels

Small round stained glass windows (roundels) form an important part of the art of the Northern and Southern Netherlands at the end of the 15th and start of the 16th centuries. Set in a larger, clear rectangular pane they functioned as decorations in convents, public buildings and the homes of wealthy citizens and Jacob Cornelisz and must have supplied designs for quite a number of them although due to their fragility not many have survived. A rare design by Jacob Cornelisz in the British Museum illustrates the accomplished and expressive style of the Master’s draughtsmanship (fig. 25).

25. Design for a roundel: a messenger kneeling and telling Abraham of the capture of Lot and the meeting of Abraham and Melchisedek; with camels, horses and figures in the landscape beyond, pen and brown ink, 1487-1533, 22.5 cm (circular)

One of the surviving small roundels, perhaps not after an original design but a reworking of a scene from a print from the Large Round Passion shows the Resurrection (fig. 26 and 27). Jacob Cornelisz’ woodcut is characteristically crowded and full of dynamic movement. The accomplished glass artist simplified the composition so that more daylight would filter through the glass, enlarged the city in the distance and gave the three Maries a more prominent position. There is no proof of this but it might be conceivable that Jacob Cornelisz supplied the glass painter with his design for the woodcut

Embroidery

Designs and prints by Jacob Cornelisz’ and his workshop were also used for embroideries on liturgical vestments. Traditionally these were made of silk, velvet or gold brocade and could be extremely expensive, especially when imported Italian gold brocade was used and gold thread was used for the embroideries themselves.

Specialist embroiderers, known as acupictores, would work from patterns, often based on prints or existing embroideries. For prestigious commissions renowned artists would be asked to design special patterns. Often a chasuble, dalmatic and cope are all made from the same material to form an ensemble, such as a surviving set originally from Hoorn (fig. 28) where Jacob Cornelisz also executed paintings on a church vault. On these vestment, the embroidered scenes, particularly that of the Baptism of Christ (fig. 29), greatly resembles the same scene in reverse in the woodcut from the Small Passion print series (fig. 30). Possibly Jacob Cornelisz received the commission for the embroidery designs around the same time as the commission for the now lost church vault paintings.

The final mystery

The exhibitions on Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen in Amsterdam and Alkmaar afforded a unique opportunity to gain more knowledge about a period in history that has been largely overshadowed by the art that was produced in the Golden Age a century later. In three accompanying posts I have attempted to sketch a more or less comprehensive overview of the work of this late medieval, virtually unknown and versatile, artist, his environment, the production process of his workshop and his relationships with some of his patrons and collaborators, however cursorily (see the entire series here). I hope you’ll bear with me if I return to this Master some time in the future.

For now, let me leave you with the intriguing lost painting of the Salvator Mundi (see also previous post) which has – understandably – not been given any attention in the exhbition catalogue. While the Salvator is only found on one surviving print by the Master as a half-length figure, he does appear in a posture and architectual setting eerily similar to the painting on an exquisite orphrey or decorative band from a liturgical vestment, one of a set of five double orphreys based on designs by Jacob Cornelisz (fig. 32). Would it not be wonderful if this intriguing painting, lost during the Second World War, one day resurfaced?

Notes:

- All works by Jacob Cornelisz (and workshop) unless indicated otherwise.

- For selected literature, see first post in this series; in addition: C. Möller, Jacob van Oostsanen und Doen Pietersz. Studien zur Zusammenarbeit zwischen Holtzschneider und Druker im Amsterdam des Frühen 16. Jahrhunderts (Niederlande-Studien XXXIV), 2005.