Johannes Torrentius (1589-1644) was a painter with a reputation as a “seducer of burghers, a deceiver of the people, a plague on the youth, a violator of women, a squanderer of his own and other’s money”. Moreover, his paintings, according to his own statements, were painted “with other paints than all other painters”, indeed, he claimed that his art was sheer magic: “it is not me who paints …”. His eccentricity and incaution led to imprisonment, cruel torture and even condemnation to the stake. His paintings were believed to have been wilfully destroyed at the time of his conviction. Only one has survived but it was not rediscovered until the previous century.

The notion that Torrentius may have been a Rosicrucian has led some recent authors to interpret historical facts in this light. Even a recent dissertation (G.H. Snoek, 2007), inventarising the early 17th century documents on the movement in the Dutch Republic, has not been able to provide conclusive proof. But contemporary accounts, too, must be interpreted with caution. In the next post Torrentius’ art, his possible use of the camera obscura, “magic paint” and more: here I will discuss the facts about his extraordinary life and conviction.

Amsterdam

Johannes Torrentius at the time of his conviction, print by Jan van de Velde (II), 1628, Rijksmuseum

Jan Simonsz van der Beeck was born in Amsterdam into a Catholic family in 1589. He would adopt the name “Torrentius” from the Latin “torrens”, a translation of the Dutch word “beeck” (brook). In 1596 his father had the doubtful honour to be the very first inhabitant of the newly built prison on Heiligeweg. He at some point left the city or was forced to leave since he was recorded as living in Cologne in 1627, ironically the year of his son’s arrest. Johannes lived with his mother Symontgen on Breestraat near Nieuwmarkt in the house of her brother Elbert.

Nieuwmarkt, Amsterdam, ca. 1780, Isaac Ouwater, Amsterdam Museum

Nothing has so far been discovered about Torrentius’ artistic training. During his trial he merely states that he is a painter by profession and has practised his art from an early age. In 1609 he received a commission for an altarpiece from the prior of the Dominicans or Predikheren in the then still predominantly catholic city of ‘s-Hertogenbosch. Torrentius, according to the testimony of one Vrouwtgen Dircx, promised that his painting would be better than the altarpiece of Our Lady in the town’s cathedral and that connoisseurs would deem it worth “at least 300 guilders”. The painting is lost, possibly it was never painted, but the story illustrates a typical trait that would repeatedly contribute to his troubles: modesty was not in his character.

According to Dudok van Heel Torrentius went to Spain as a young man and upon his return had abandoned the Catholic faith which does not seem to have been replaced by Protestantism. On 14 January 1612 the bans were read on his marriage with 22-year-old Neeltgen van Camp.

Signature of Johannes van der Beeck and Neeltgen van Camp, 1612, from Bredius, 1909

It was not to be a happy marriage. and the couple separated a few years later. In 1621, Torrentius failed to pay alimony and was briefly sent to prison (a notarial document dated 21 May 1621 mentions that he is “these days in prison in Amsterdam”). Upon his release he moved to Haarlem where he stayed in the house of a friend, the wealthy merchant Christiaen Coppens, on Zijlstraat while maintaining a separate studio.

Conspicuous behaviour

Torrentius’ painting career was successful and his wealth as well as his flamboyance began to attract followers. He was reputedly a handsome man, always dressed in rich satins and silks, groomed to perfection and he spoke with a somewhat posh accent. Not only did he attract male followers, but women were drawn to him like a magnet, many “to the chagrin of their husbands”. Constantijn Huygens, who had met the painter, wonders about the Torrentius phenomenon in his unpublished Memoires of my Youth (begun 1629):

… he has turned the heads of the sect that had formed around him to such a degree that they came to consider his vices as virtues and enveloped his godlessness in a kind of religious cult and adoration.

The intolerant Republic

Satirical print on the Synod of Dordrecht, Simon Goulartius, 1619. Goulartis was a Remonstrant preacher who was ousted from his function in 1619. In the print nearly all the delegates wear devil’s or bull’s horns.

While the war against Spanish catholic dominance was ever present during the first decades of the 17th century, ideological differences between the conservative Dutch Calvinist Protestant minority on the one hand and the Remonstrants and libertines on the other nearly led to civil war in 1617/18. The Calvinists or Counter-Remonstrants achieved a Phyrric victory at the Synod of Dordrecht in 1619. As a result Remonstrants, like the catholics before them, were prohibited from publicly holding religious services; if caught, they were severely fined. In this repressive climate one would do best to behave inconspicuously but that was not in Torrentius’ nature. “What is God, do you know God, did you see him, what kind of little thing is God?”, he is reported to have said. When even the moderate Remonstrants had to keep their mouths shut, a free-thinker like Torrentius had no chance at all.

Trial and conviction

As early as 1621 the Haarlem magistrates had consulted the church council about the painter and in 1625 they turned to theologians at Leiden University for advice. On 29 June of that year the Court of Holland in a letter to the Prosecutor, Mayor and Aldermen of Haarlem warns them of the dangers imposed by Rosicrucian sect (secte den Roose Cruce) and of “one Torrentius, who is said to be one of the principal members of the aforesaid sect.” Apparently the allegation was based on hearsay. In his own time, too, there was no definite proof linking him with a “secret society”.

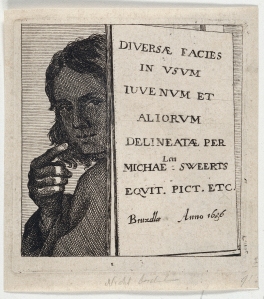

Print marked “Torrentius fec” today attr. to Pieter Quast (1605-47), possibly a copy or parody of a work by Torrentius, Rijksmuseum

It is perhaps not surprising that, openly flaunting his critical attitude towards the Bible and Calvinist preachers, Torrentius was finally arrested on 29 August 1627. Moreover, most of his paintings were considered to be pornographic and several of them were confiscated by the Haarlem magistrates and exhibited in the city hall before, presumably, most of them were destroyed. In the State Papers of Charles I, an admirer of his work, is a curious entry marked “A note of Torrentius pictures, 1629, at Liss [Lisse] and Harlem”: “His other bawdye pictures such as his friends saye he intended should never be seen are to be seen in the town house at Harlem.”

It turns out that Torrentius’ main detractors were two Dutch reformed ministers, Henricus Geesteranus and Dyonisius Spranckhuysen, who remained behind the scenes and incited others to testify against the artist. Called to testify, Roeland Clarenbeecq, host of the Haarlem inn De Vergulde Valck remained silent when asked “whether Torrentius drank the devil’s health and in what company.” Lambrecht Maertensz. Schapenburg and his wife, who ran an inn in Delft, testified against Torrentius but afterwards stated that two preachers, later identified as Gideon Sonnevelt and Henricus van Linden, known as the “scourge of the Remonstrants”, had visited them with a letter specifying what they should say in court.

Torrentius was interrogated five times but he would not confess and so he was tortured to loosen his tongue – to no avail.

His shinbones were first clamped in irons. Then his hands were tied behind his back and he was hung on his arms with several weights pulling at his feet. Next the executioner and his assistant pulled his legs with all their might. This not being enough, two other men were called in to assist in pulling till his limbs would separate. (Samuel Ampzing, in: Description and Praise of the City of Haarlem, 1628)

View of the Town Hall on Market Square, Haarlem, Cornelis Beelt, c. 1640, Frans Hals Museum. The Town Hall functioned as administrative center and as courthouse

A letter from Stadtholder Frederik Hendrik dated 13 January on Torrentius’ behalf had no effect and on 25 January 1628 Torrentius, paralysed, was carried on pillows into the courtroom to hear the verdict. His lawyer, Reinout Schoorel, pleaded in his defence, but was told that Torrentius would be sentenced extra ordinaris because of the heinousness of his crimes, meaning that he would not be able to defend himself or appeal against the verdict. The advice of five lawyers from The Hague, sought by the Haarlem magistrates, corroborated this.

No attention was given to the counter statements of defence witnesses, among which the distinguished Nicolaes van der Laen, former Mayor of Haarlem. Torrentius was convicted on thirty-one counts, because of “his godlessness, abominable and horrifying blasphemy, and also for terrible and very harmful heresy” and had to pay legal costs. The Prosecutor demanded death at the stake but this was overthrown by the city council and commuted to twenty years imprisonment. Torrentius was thirty-nine years old; with abominable prison conditions at the time this constituted more or less a life sentence.

The medieval dungeons below Haarlem’s Town Hall

Torrentius did not remain passive. He sent a request to the Court of Holland stating in no uncertain terms that he had been rigorously tortured on account of the false testimony of “an innkeeper and his wife from Delft”, (the Schapenburgs), his injuries still being so severe that he “still cannot move [my] limbs”. He complained about the injustice of the extra ordinaris proceedings whereby all means of defence were taken away from him. This, he stated, was a “violation of all justice, reasonableness and fairness”. The reply was a simple “nihil”. Undeterred, Torrentius sent a request to the Supreme Court, the highest legal authority, but again the reply was “nihil“.

Frederik Hendrik by Gerard van Honthorst, 1631, private collection

Only one road was open now: Stadtholder Frederik Hendrik who had already appealed on the painter’s behalf. In a letter to the Prince Torrentius again invoked his invalidity resulting from the cruel torture. The Prince acted immediately, asking the Haarlem authorities whether Torrentius could not be housed elsewhere so that he could practice his art. It took the Haarlem magistrates months to respond. Torrentius exaggerated, they wrote: he was regularly seen by a good doctor and an excellent surgeon and his friends took delicate spices and food, clean linen and woollen clothing to him. He would be allowed to paint, they said, should he have expressed the desire – but he had not. They added that to allow him to live elsewhere would, since he could not be trusted not to propagate his heresies and corrupt the city’s youth, endanger the good Christian citizens of Haarlem.

An interesting event occurred on 29 January 1629: the painters Frans Hals, Pieter Molijn and Johan van de Velde were requested by the magistrates to inspect the cell where Torrentius was held captive and to report on the possibilities to paint there. Alas, the report is now lost.

Johannes Wtenbogaert, 1633, Rembrandt, Rijksmuseum

The case had created a stir among Remonstrants who had themselves been persecuted. Preacher Johannes Wtenbogaert wrote to the Remonstrant scholar Hugo de Groot who had escaped and fled abroad: “In the country there is much talk about a Torrentius.” Torrentius himself was not without influential and learned friends. Petrus Scriverius, Haarlem writer and scholar, who had himself been fined several times on account of his Remonstrantism, visited Torrentius in prison on 29 March 1629. On that occasion Torrentius wrote a poem in Scriverius’ Album Amicorum.

Poem by Johannes Torrentius in the Album Amicorum of Petrus Scriverius, 23 March 1629, ending “God be praised”, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag

Release

Dudley Carlton by Michiel van Mierevelt, c. 1620, National Portrait Gallery

Torrentius and his troubles were the subject of correspondence between English diplomat to the Netherlands Dudley Carleton, who also acted as an art agent, and Charles I. The latter wrote to Stadtholder Frederik Hendrik who in turn appealed once more to the Haarlem magistrates. They responded stating that, although they had encouraged him several times to paint, Torrentius had so far not done so, indicating that to release him so that he could paint again was no valid reason, even if the English had vowed they would be responsible for his conduct. The Haarlem authorities must have given in eventually because a letter from Carleton to the Secretary of State in December 1630 speaks of Torrentius going to England with certain pictures for sale. These in all likelihood were the paintings Torrentius’ friend Van der Laen had kept safe in his country house in Lisse during the painter’s incarceration.

Several paintings by Torrentius are mentioned in Charles I’s inventory but not a trace of them has been found nor any trace of the artist’s life in England. In fact, nothing is known other than a brief general description of the painter’s life by Horace Walpole in Anecdotes of Painting in England, vol. 2 (1826), ending with the somewhat cryptic remark that “giving more scandal than satisfaction, he returned to Amsterdam.”

Why Torrentius left England in 1642 is unclear. One possibility could be the outbreak of the English Civil War which would eventually lead to the beheading of his patron. It remains odd that he chose to return to a country that had essentially banished him. And indeed it did not last long before Torrentius was imprisoned yet again, this time in Amsterdam, on the old charges. His incarceration was brief this time, perhaps because he was ill. He returned to his mother’s house where he died, some say of syphilis. On 7 February 1644 he was buried in the Nieuwe Kerk (New Church), which is remarkable for someone considered to be a heretic, a blasphemer and a devil worshipper.

Interior of the Nieuwe Kerk, Jan Veenhuysen, 1665, Stadsarchief Amsterdam

Was Torrentius a Rosicrucian? One cannot exclude it, but there is, so far, no concrete evidence. In all likelihood there was no organised Rosicrucianism in the early 17th century Republic but rather a libertine subculture that was considered dangerous by the newly established Dutch Reformed Church and therefore by the State at a time when religion and politics were inextricably entwined. After all, Torrentius had followers, although Huygens describes the clan around the painter as “dim-witted” and credulous. But the authorities, so soon after closely avoiding civil war, could not afford to take risks. The painter behaved much like a modern pop star and deliberately provoked, loved his wealth and flaunted it at a time when modesty was deemed not only a religious virtue but a duty. Not being a poorter (citizen) of Haarlem, he became an easy target to make an example of to hold up to other free-thinkers in the city.

Selected literature:

- Leyds-veer-schuyts-praetgen tusschen een koopman ende borgher van Leyden (etc.), 1628, a popular pamphlet in verse about the case, contains amongst others, the defence plea by sollicitor R. Schoorel.

- T. Schrevelius (1645 and 1648) and S. Ampzing’s (1628) Descriptions of the city of Haarlem contain chapters on the case.

- Constantijn Huygens, Mijn Jeugd (Memoires of my Youth), written in Latin, was begun in 1629 and abandoned two years later. Intended by Huygens for private circulation, the manuscript was not published until 1897. I have used the 1987 translation by C.L. Heesakkers.

- Most court documents and correspondence are quoted in Abraham Bredius, Johannes Torrentius: Schilder, 1909 and, by the same author, “Torrentius: een nalezing”, in Oud Holland, 1917.

- A.J. Rehorst, Torrentius, 1939, is devoted to proving Torrentius’ Rosicrucianism.

- S.A.C. Dudok van Heel, De jonge Rembrandt onder tijdgenoten: godsdienst en schilderkunst in Leiden en Amsterdam, dissertation, 2006.

- G. Snoek, De Rozekruisers in Nederland, dissertation, 2007.