What is it about art that brings out the worst in some people? The answer is, sadly, that its monetary value increasingly takes over from its artistic and emotional merit. On 7 December 2013 the exhibition Natural Beauty, from Fra Angelico to Monet opened at the Groninger Museum. The exhibition shows part of the collection of the excentric German millionaire Gustav Rau (1922-2002) who, over a period of four decades, built a collection consisting of 786 paintings, sculptures and artifacts spanning six centuries. Unintended by Rau who designated his collection to be sold after his death to benefit charity, the collection has been the subject of legal and even political battles for years, starting during Rau’s lifetime and continuing until today.

Two passions

Gustav Rau was destined to follow in his father’s footsteps and work for the prosperous Stuttgart family business in auto parts. At the outset of World War II he was drafted into the Wehrmacht but managed to escape to London where he was held captive as a German national. Having returned to Stuttgart after the war, he started to collect art at the age of 38, his first purchase being Gerard Dou’s small trompe l’oeil painting of a cook.

Soon after he turned forty Rau began studying medicine, specialising in tropical diseases. He had never loved the family business and had only studied economics to please his parents. At forty-eight, a year after his father died, he sold the family business for DM 400 million (USD 110 million) and found his true calling in Africa, eventually settling in Zaire (now Congo-Kinshasa), building a clinic in Ciriri where he lived in spartan conditions. Not surprisingly, his great example was Dr. Albert Schweitzer. But corruption ran rife in Zaire with in its wake appalling poverty and it was not easy to accomplish much of anything there. Perhaps art was an antidote to all this. Every few months Rau traveled to Europe where, in his ankle-high hiking boots and khakis he was a frequent and memorable sight in auction rooms.

Rau, a devout Christian, never married and died childless. It seems almost impossible to reconcile the dichotomy in the man’s character: on the one hand a passionate art collector, spending millions on priceless artworks; on the other equally passionately dedicated to alleviating suffering in a small corner of Africa. Neither was an affectation. In both, it seems, he was equally sincere. When it came to art, after having been repeatedly duped in the early years of buying, Rau selected each work personally, shunning professional advice. The economist in him made that he was rarely tempted to offer more than the price he had intended to pay. He did not focus on a single area of art or attempt an academic survey of period or theme. Each individual work triggered his personal esthetic and emotional response and each acquisition was bought for the pleasure of looking at it. Only: he did that very rarely. Everything remained stored in a duty-free warehouse in Embrach, Switzerland for decades.

If there is any unifying theme running through the collection it has to be the human face, not surprising perhaps for a great humanitarian. One feels the humanity in the characters in his collection, not only in paintings, but also in the sculptures, in the medieval depictions of the suffering Christ. But his business sense never left him: he would seldom spend more on an art work than he had originally intended.

Due to health problems (a cerebral hemmoraghe after complications from double knee surgery) and the increasing instability in the region, Rau left Ciriri forever in 1992, settling in Monaco and later returning home to Germany. Throughout Rau built his art collection to form a legacy that would ultimately benefit the Third World by diminishing misery and disease through preventative practices and the distribution of medication and food. To this aim Rau established three foundations in the 1970s and ’80s. His plan at the time was to donate his entire fortune in the Crelona Foundation which would then pay his living expenses; everything remaining after his death would go to a fourth foundation: the Rau Foundation for the Third World.

Downhill

But in Monaco the ailing Rau had begun to medicate himself, devising a pharmacological programme for himself that proved disastrous. He was sometimes discovered roaming the streets, lost and disoriented. This raised doubts about his mental faculties and lawsuits followed to prove him incapable of running his affairs. In March 1998 a financial administrator was appointed by the Monaco court. Later that same year a Zürich lawyer and board member of one of Rau’s charitable foundations successfully petitioned the Swiss government to freeze Rau’s Swiss bank account and the art works on the grounds that his “entourage” (Rau’s personal secretary and his confidente, a graphologist) might take advantage of the ailing collector. The “entourage” appealed and legal battles in Switzerland, Monaco, Germany and Liechtenstein followed.

In 1998, with the legal battles over his competency raging, Rau took action to prove that he was not the helpless vegetable his detractors made him out to be. With the help of a former art lecturer at the Sorbonne exhibitions of his masterpieces were staged, originally intended to go to only five Japanese museums. The Swiss government permitted the art to leave the country on condition that it would return immediately but it did not: after Japan Rau sent it to the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris, igniting a diplomatic battle that pitted the French government against the Swiss. The exhibition then traveled to Rotterdam, Cologne, Munich and Bergamo and caused a sensation wherever it went.

Rau eventually seized control over his affairs and held a press conference in September 2001 announcing the donation of his entire collection to UNICEF Germany. “I know my material possessions are in good hands now. I entrust them to an organisation that is committed to one cause only, to which I have given my own life: helping destitute children”, an emotional Rau said. At the same time he stipulated that the core collection, some 125 paintings, should stay together for a twenty-five year period, which will end in 2026. Gustav Rau died in early January 2002. But it didn’t stop there. The legal wrangles did not only follow from doubts about Rau’s mental capacity but also from his many wills: which was actually valid? Moreover, if the court would rule that Rau had been mentally incompetent in September 2001, the donation to UNICEF Germany would become null and void.

On top of it all, Rau’s death was considered suspect. In 2003 the Stuttgart district attorney opened a homicide investigation on the suspicion that the doctor had been poisoned. Excessive doses of Parkinson medication had been found in Rau’s body that could not be justified as medication; it was further believed that Rau, greatly weakened, could not have administered these doses himself. The case was eventually dismissed but doubts remain to this day.

More legal hassles

In spite of a 2008 German verdict deciding that Rau was competent at the time when he left his collection to UNICEF Germany and that the organisation is therefore the rightful heir, the legal wrangles only continued. It would go too far to list them all here, but the latest inquiry is being conducted by the Zürich prosecutor’s office on the basis of a complaint brought by the council of Bülach, the district where Rau had stored the collection for years, just days before a major auction at Bonhams in London of ninety-two works from the collection that included paintings by Pissarro and Fragonard. The auction, on 5 December 2013, went ahead and Fragonard’s portrait was sold for a record 17.1 million pounds ($27.9 million). The painting had been Rau’s personal favourite. The aim of the current complaint seems to be to have Rau’s collection returned to Switzerland. But there is no destination envisaged should the district council win the case which, in any case, is very doubtful. Most likely it would end up in the duty-free warehouse once again.

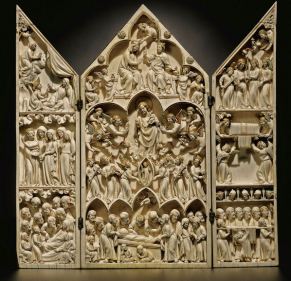

The remaining art has gradually been sold through three auction houses to benefit UNICEF Germany’s humanitarian work: Sotheby’s and Bonham’s in London and Kunsthaus Lempertz in Cologne. One of the works recently auctioned at Sotheby’s is an exquisite and rare early French ivory triptych with scenes from the Life of the Virgin with traces of original polychromy and gilding, dated c. 1310-20, fittingly known today as the Gustav Rau Triptych.

The question can validly be asked whether UNICEF Germany is not being compromised by all this and whether, with hindsight, they might even regret Gustav Rau’s donation. Time and time again reactions to new allegations appear on their website – it keeps their lawyers very busy. It is sad that a well-meant and generous humanitarian gift has become so encumbered.

Michael Sweerts

Readers of this blog will remember my fascination with the Flemish painter Michael Sweerts. Two works in the Rau collection to be exhibited until 2026 are by him, that is to say: one of them is in such a deplorable state that it can no longer be established if it is an autograph work or a contemporary free copy of the painting called The Schoolroom, discussed in an earlier post.

The other is an autograph work now in the exhibition in Groningen: it is one of the paintings of the Seven Acts of Mercy series. The Rijksmuseum so far owns four of the series. I hope that when the time comes, 2026, they will consider buying Harbouring the Stranger, which is every bit as mysterious and compassionate a work as the others in the series.  The composition is evidently based on the iconography of the travellers on the road to Emmaus where Christ, dressed as a pilgrim, meets two of his disciples. It is the man in the middle who is of particular interest. He is staring straight at the viewer, drawing us into the scene. It is Michael Sweerts himself. About thirty at the time, his features are recognisable from, for example, his self-portrait in the Uffizi. Not only would the Rijksmuseum acquire another painting in this magnificent series, but at the same time a Sweerts self-portrait. The economist in Gustav Rau would be pleased: two for the price of one.

The composition is evidently based on the iconography of the travellers on the road to Emmaus where Christ, dressed as a pilgrim, meets two of his disciples. It is the man in the middle who is of particular interest. He is staring straight at the viewer, drawing us into the scene. It is Michael Sweerts himself. About thirty at the time, his features are recognisable from, for example, his self-portrait in the Uffizi. Not only would the Rijksmuseum acquire another painting in this magnificent series, but at the same time a Sweerts self-portrait. The economist in Gustav Rau would be pleased: two for the price of one.

Note:

For a full overview of the Rau Collection (texts in German), see:

- http://www.sammlung-rau-fuer-unicef.de/index.php?level=album&id=5 (this comprises the art on display until 2026);

The three catagories were compiled in September 2013 and do not incorporate the sales results of the auctions held in the fall of 2013.