From 21 March Rembrandt’s most ambitious painting of which only a fragment (now in Stockholm) remains will be temporarily exhibited in the Rijksmuseum. The Nocturnal Conspiracy under Claudius Civilis, its full title, was created for one of the galleries of the newly built Town Hall (now Royal Palace) but it hung there only briefly. Why was it taken down? Who reduced the large canvas to the much smaller central fragment and why? An investigation, starting with the peculiar genesis of the series of paintings for the galleries of Amsterdam’s Town Hall, of which Rembrandt’s painting formed part.

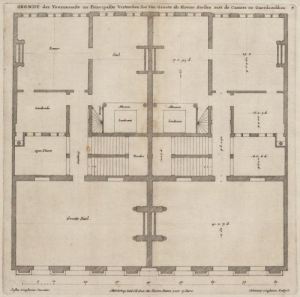

Anyone visiting the galleries today will immediately be struck by the monumentality of these vast spaces, more than eleven meters high. On their outer sides they gave access to administrative chambers (now Empire period rooms) while on their inner sides windows look out on two inner courtyards. The galleries receive daylight only from the windows giving on to the inner courtyards so that the corners are especially dark, yet this is precisely where the paintings depicting the Batavian Revolt are placed.

The enormous arch-shaped works (5.5 x 5.5 meters) are situated above the lower moulding and are enclosed by the galleries’ barrel vaulting. In the north-east corner hang two canvases by Jacob Jordaens, in the south-east corner a work by Jan Lievens and a work by Govaert Flinck and Jürgen Ovens, the latter replacing Rembrandt’s Claudius Civilis, in the south-west corner two frescos by Giovanni Antonio de Groot. The series was never completed: the fourth corner has always remained empty. Similarly unfinished is the series with four biblical heroes by Jordaens that was planned in the arches of the east and west galleries with access to Citizens’ Hall (the Burgerzaal). Only two (scenes with Samson and David and Goliath) were completed.

The analogy between the Batavian Revolt and Dutch Revolt against Spain

When the Town Hall was inaugurated on 29 June 1655, the building was far from finished but the destruction by fire of the medieval town hall next door necessitated the city’s administrators to move in prematurely. The idea for a series of gallery paintings depicting the Batavian Revolt against the Romans (69-70 AD) and complimentary Old Testament and classical heroes stemmed, so the poet Joost van de Vondel tells us, from Cornelis de Graeff (1599-664), one of Amsterdam’s four Burgomasters and a member of one of the city’s powerful and wealthy regent families.

As early as 1584 the Stadtholders of Holland, princes of the House of Orange, military commanders in the Eighty Years’ War against Spain that had ended in 1648, were likened to Claudius Civilis and Brinio, the leaders of the Batavian uprising. The story had become hugely popular after 1600 following the publication of Tacitus’ Histories (in Latin) and was featured prominently both in texts and images, the most important set of which, and also the most important iconographic antecedent of the paintings in the Town Hall, was produced by the Italian Antonio Tempesta based on designs by Otto van Veen (1612). In the spirit of the Twelve Year Truce (1609-1621), a lull in the hostilities, the prints did not glorify the war itself but rather the resulting peace which must have struck a chord with Amsterdam’s Burgomasters who envisaged not only a stunning town hall expressing Amsterdam’s growing prosperity but also a monument to the restoration of peace.

Govaert Flinck and Jürgen Ovens

Govaert Flinck, study for the Conspiracy under Claudius Civilis, 1659-60, Hamburger Kunsthalle, b/w image

Naturally, to receive a painting commission for the magnificent new Town Hall, soon to be known as the “Eighth Wonder of the World”, was extremely prestigious. Nothing had happened by 1659 but in that year the commission suddenly had to be rushed on account of the impending visit by members of the House of Orange on 24 September of that year. As Vondel tells us in another poem, it was Govaert Flinck who managed to complete four gigantic sketches in August 1659 in the space of only two days. Because of this bravura act and because his designs, largely based on Tempesta’s prints, pleased the Burgomasters, he was awarded the commission for the entire series: he was to paint “12 works for the galleries, two a year at 1000 guilders a piece.” But Flinck died unexpectedly on 2 February of the following year without having completed any of the permanent canvases. This time, the Burgomasters prudently decided to spread the risk and invited several renowned painters to submit sketches and drawings for the series.

Govaert Flinck/Jürgen Ovens, the Nocturnal Conspiracy under Claudius Civilis during recent restoration

It was Rembrandt’s Nocturnal Conspiracy under Claudius Civilis that replaced Flinck’s temporary painting of the same subject but when that was taken down, with another important visit (that of the Bishop of Cologne) scheduled soon afterwards, the empty space needed to be filled in a hurry and Flinck’s gigantic sketch was retrieved from storage. The German artist and former Rembrandt pupil Jürgen Ovens was commissioned “to work up a sketch by Govert Flinck into a complete ordonnation.” Ovens painted over Flinck’s faded water-colour and charcoal composition in oils and added another ten or twelve figures. On 2 January 1663 he was paid a paltry forty-eight guilders for the four days he had spent completing Flinck’s work. The planned replacement of Flinck/Ovens’ painting never materialised.

In 1664, due to a shortage of finance, the city governors decided to postpone all commissions or purchases of paintings for the Town Hall for five years. Almost illegible now, the painting still hangs in the arch in the south-east gallery today. Already severely compromised – unprimed and painted with water-based paint so that it discolours as it ages – the painting’s problems were compounded by earlier treatments by people who had no understanding of its unique nature. In the 18th century, for instance, the painting was lined using glue, a treatment that involves considerable amounts of water so that Flinck’s gum paint was partially dissolved. In addition the painting was varnished several times which is totally unsuitable for water-based paint. But the most damaging of all was the wax-resin lining of 1960 which permeated the fine linen so that it has now acquired a dark orange-brown colour.

Jan Lievens

Somewhat better fared Jan Lievens’ painting next to it. Lievens received his commission on the same day as the Antwerp master Jacob Jordaens, 13 January 1661. Both finished their paintings within six months, both executed the final touches in situ. Lievens’ Brinio raised on a shield shows the Batavians’ allies, the Canninefates, electing Brinio as their leader. To honour him, Brinio’s warriors raise their new commander on a shield, a scene also illustrated in Tempesta’s prints. The scene was significant for the Dutch Republic. Heated discussions concerning the Stadtholder’s hereditary leadership were taking place in which Cornelis de Graeff was a key figure. Brinio’s election made the point that military leaders should be elected and not installed by right of birth, a model of government that the Amsterdam Burgomasters strongly supported.

Jan Lievens, small-scale study for Brinio raised on a shield, oil on paper on canvas, 60×59 cm, Amsterdam Museum

The painting is more colourful and lighter than most of the other canvases in the series but even so specific passages such as in the sky have darkened considerably. In addition, Lievens did not wait for underlying paint layers to dry thoroughly before applying further layers and as a result, particularly in shadow paints, the paint surface has crinkled and developed deep cracks which makes it difficult for layers of old varnish, grime and wax to be removed.

Jacob Jordaens (and workshop)

From an account referring to his accommodation at the Lijsveltse Bijbel (an inn on Warmoesstraat) it appears that the Antwerp master Jacob Jordaens submitted his first painting for the series shortly before or after 17 June 1661. A Roman camp under attack by night is the only battle scene in the galleries. It is a complex, baroque composition showing a mass of writhing figures and the impact of the work is heightened by strong contrasts between light and dark. His Peace between the Romans and the Batavians illustrates the final episode of the story. In addition, Jordaens made a painting for the series of heroes in 1662, showing Samson defeating the Philistines. The Burgomasters were delighted with his work and awarded the painter a gold medal which was presented to him on 13 June 1662, along with his fee of 3000 guilders: 1200 guilders for the two Batavian paintings and 600 guilders for the Samson.

In November 1664 as we have seen, the Burgomasters adopted a resolution not to buy or commission any further paintings for a period of five years, but two weeks later they made an exception:

Approval is given to fill the space in the gallery that has already been reserved for a painting with a work that Jordaens has already begun, representing the story of David and Goliath. Taking consideration for his advanced years [Jordaens was 71 years old at the time], one may assume that the master will not be working as an artist five years hence.

Jordaens completed David and Goliath, the second and final painting for the series of heroes soon thereafter.

What is interesting for our understanding of the architectural context is Jordaen’s modello for the Samson. When King Louis Napoleon took up residence in the Town Hall in 1808, making it his royal residence, its appearance was changed dramatically. Today the galleries and their vaultings are clad in white marble, but in the 1660s the painters would have known that their pieces would connect above with a stone-grey surrounding, just as they knew that in the walls below a marble finish was intended.

This is what Jordaens’ modello shows: the struggle is enacted above a trompe l’oeil arch that was intended as an illusory continuation of the actual arch above the doorway to the Citizens’ Hall. For this arch a white marble finish was envisaged and so the trompe l’oeil arch on the modello is also painted whitish-grey.

Giovanni Antonio de Groot’s “secreet”

Even more clues to the architectural finish of the galleries are found in the two frescos by the Italian artist of Dutch decent Giovanni Antonio de Groot who appeared before the Council of Amsterdam in 1667 where he presented ambitious plans for the completion of the decorations. By that time, the paintings were in a deplorable state as damp in the walls had not only damaged the plaster layer but had also caused a number of paintings to deteriorate badly. The Council acknowledged that the existing paintings had already largely perished and that the paintings were barely visible from below. De Groot claimed to have invented a secreet, a secret recipe that could be used to stabilise the plasterwork and prevent it from detaching from the wall. If granted the commission, he would paint eight frescos with scenes from the Batavian cycle. Primarily because of his proposed solution he was granted the commission. On 3 October 1668 he was paid for two frescos but for some unknown reason no other frescos were produced and the – damaged – original paintings remain in place until this day.

Giovanni Antonio de Groot, the Peace Negotiations between Claudius Civilis and Quintus Petillis Cerialis

De Groot’s works are curiously clumsy and do not represent the artistic qualities of this artist. This is because, in spite of his “secret recipe”, during the course of the first half of the 18th century the frescos must have been quite seriously damaged. Jan van Dyk (ca. 1690-1769), a restorer of paintings employed by the City and never one to mince words, described their condition as follows:

In the corner by he Thesaurie Extraordinaris, two pieces have been painted in fresco, which are actually good artistically, were it not for the brackishness in our walls, which have been spoiled by the sweated salt, and not much that could be done about it, [and also] had not one of the Know-nothings [“Weetnieten”] of art scrubbed both these pieces with water and Brussels sand, to which there are still living witnesses who confirm this, yes, who even warned him.

Van Dyk deemed the situation so serious that, in 1756, he thought restoration no longer possible. He decided to overpaint the frescos completely. In doing so, he remained faithful to De Groot’s composition and left remnants of the original composition visible wherever possible. Unfortunately, at the end of the 19th or the beginning of the 20th century the works were overpainted once more, this time not closely following De Groot but Van Dyk. The result today is that the works have become even further removed from their original appearance.

Detail from Giovanni Antonio de Groot’s Peace Negotiations between the Romans and the Batavians showing the trompe l’oeil architecture

De Groot’s frescos do, however, provide an important clue as to the original 1660s wall finishes envisaged by architect Jacob van Campen, namely that the now white vault must originally have been sandstone-coloured: along the curved upper edges of both frescos is a trompe l’oeil architecture of sandstone blocks which must have been intended as a continuation of the surrounding “real” architecture, creating the illusion that the heroic deeds of the Batavians were actually being acted out before the eyes of the visitors in the galleries.

As a consequence of the present-day white finish of the vaults, we perceive the gallery canvases as darker than they really are. In a surround of sandstone the paintings must have been decidedly more legible even though, as we have seen, the corners in the galleries where they hung were dimly lit from the start. We will see in the next post how Rembrandt was the only artist who, in his majestic Nocturnal Conspiracy under Claudius Civilis, took into account the dark location where his painting would hang.

Acknowledgement

I am greatly indebted to the publications with regard to the recent (2007-2009) restoration of the paintings in the galleries which present hitherto unknown facts regarding the paintings’ genesis and restoration history.

NB: Amsterdam’s 17th century Town Hall (now Royal Palace) is open to the public when not in use by the Dutch Royal family.