Following from the previous post which discussed the (indirect) relationship between Rembrandt’s group portrait of the Company of District II commanded by Captain Frans Banninck Cocq, known as the Night Watch, and Marie de’ Medici’s 1638 visit to Amsterdam, in this post a more intimate look at the painting. The Night Watch was created as a very public work and that is what it is still to the extent that it has become a national symbol. Divorced from its original context, the painting has become less accessible. In this post an attempt to break through the barriers of its fame and to really see this in some ways controversial and in other ways compromised masterpiece.

The standard-bearer

The flamboyant standard-bearer Rembrandt painted in 1636 could be an actual portrait or perhaps rather a tronie or a modello intended to procure lucrative commissions from the wealthy members of the civic guards companies. A civic guards group portrait, the sitters for which invariably belonged to the wealthy segment of Amsterdam society that could afford to commission paintings, might lead to individual portrait commissions. The standard-bearer is shown in antique costume for which Rembrandt may have used a print by the Italian engraver Teodoro Filippo di Liagno.

The parallels between the portrait and Di Liagno’s print are striking: the pose with the hand at the waist, the notched bonnet with feather, the wide sleeve with slashes and the drooping moustache seem too similar to be coincidental. The standard bearer’s costume is that of a Landsknecht (literally: servant of the land) of the beginning of the 16th century to which Rembrandt added 17th century elements such as the sash, gorget and standard which associate the man with a civic guards company. Rembrandt would borrow again from his extensive print collection to add symbolic and historical reference to the Night Watch.

Where was the Night Watch painted?

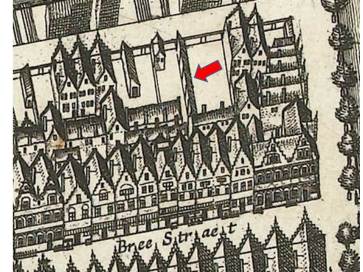

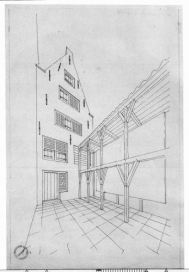

Rembrandt’s house on Breestraat as it was thought to have looked in the 17th century, Cornelis Springer, 1853, Amsterdam City Archive

We do not know when Rembrandt obtained the commission for the Night Watch. The painting is signed 1642, in all likelihood the year of completion, but such a large painting would have taken quite some time to create. A question which has so far not been answered satisfactorily is where such a large canvas was painted. Prof. Ernst van de Wetering has suggested that artists may have painted civic guards group portraits in “empty churches” but the problem is that there were none in Amsterdam. Fairly soon after the Reformation took hold at the 1578 Alteration, catholic churches were converted for protestant worship, a process that would have been completed by the 1630s. In addition, the light in a church would hardly be conducive to painting.

In the deed of the execution sale of Rembrandt’s house on Breestraat, drawn up on 1 February 1658, a “wooden structure in the yard” is mentioned that shared a wall with the neighbouring house. Lesser known documents in the Amsterdam municipal archives specifically mention a gallery, presumably referring to this structure, as early as 1617. Courtyard galleries were not uncommon and were used by craftsmen or for household chores. In bad weather the open side of such a gallery would be covered with tarmac. An early birds-eye map of Amsterdam might well show the gallery in the courtyard behind Rembrandt’s house

Rembrandt’s gallery is again mentioned in a deed of 1643 concerning the sale of a property behind his house. This deed specifically mentions “the small gallery built by the aforementioned Rembrandt against the wall of this house”, which suggests that by that time the painter may have altered the existing gallery, perhaps specifically to accommodate the Night Watch. Once finished, the canvas would have been relatively easy to transport, rolled up, through the passage Rembrandt shared with his neighbour the painter Nicolaes Eliasz Pickenoy, through Staalstraat to its destination: the Great Hall of the Kloveniers headquarters.

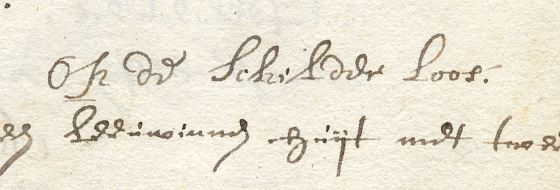

Page fragment from the 1656 bankruptcy inventory mentioning the “schilder loos”, Amsterdam City Archive

In the famous bankruptcy inventory of 1656 a schilder loos is mentioned which was translated as a “painter’s rack”. It is not clear whether this “rack” was located inside or outside the house. Could the loos possibly refer to the “small gallery” in the 1643 deed and had Rembrandt, at some later time, perhaps boarded its open side up so that it could serve as a storage area for paintings? The paintings mentioned as being in this loos include a “large Danaë”. This may be the painting now in the Hermitage, which was painted much earlier. The painting was initially finished in 1636 and later altered by Rembrandt some time before 1643. That it was still in his possession could mean that Rembrandt had hung on to it for some unknown reason or had found it difficult to sell because of its large size.

Location and illusion

Rembrandt would have been very aware of the intended location of the Night Watch, furthest from the entrance to the Kloveniers‘ Great Hall and at an angle to the wall which had a fireplace. Entering the hall, it would have appeared as if Captain Banninck Cocq and his Lieutenant emerged from the darkness of the corner at the moment the order to march is given and the drummer beats his drum, causing a dog to cringe in fright. The company behind them, still in disarray, will soon fall into formation.

For the illusion of movement and action to work best, the painting must have hung at floor level, perhaps with only a narrow plinth separating it from the floor so that the life-size figures of the Captain and the Lieutenant were almost at eye level with the beholder. Unfortunately neither the exact dimensions of the hall nor the exact measurements of the paintings are known: all three civic guards paintings on the long wall were cropped to a greater or lesser extent at some time in their existence. There is, however, a notarial deposition of 19 July 1642 in which two carpenters, Grismund Claesen and Johannes Doots, state that:

Some days ago [we] installed the painting or likeness of the company of the honourable Captain Jan Claas van Vlooswijcq [by Pickenoy] in the great hall of the new Cluveniersdoelen and secured it in its permanent surround.

Pickenoy’s painting was the Night Watch‘s neighbour, hanging in the center of the long wall in the Great Hall. Since no frame-maker was involved, this suggests that the paintings were incorporated in panelling which would have brought the room together in a single impressive entity.

Two contemporary assessments of painting techniques

Samuel van Hoogstraten, who almost certainly witnessed Rembrandt paint the Night Watch, made interesting observations regarding the illusion of depth which, in Rembrandt’s painting, constituted a revolutionary leap forward when compared with other civic guards portraits. The latter focused on accurate likenesses which meant that for each member of the group to be awarded the same painterly attention, compositions were of necessity fairly static and one-dimensional.

In his Introduction to the Academy of Painting, or the Visible World, published in 1678, although not directly referring to the Night Watch, Van Hoogstraten described principles that apply to Rembrandt’s painting. With regard to coarse surfaces and the rendering of depth in a painting, kenlijkheyt (perceptibility), he writes:

I therefore maintain that perceptibility [kenlijkheyt] alone makes objects appear close at hand, and conversely that smoothness [egaelheyt] makes them withdraw, and I therefore desire that that which is to appear in the foreground, be painted roughly and briskly, and that that which is to recede be painted the more neatly and purely the further back it lies. Neither one colour or another will make your work seem to advance or recede, but the perceptibility or imperceptibility [kenlijkheyt or onkenlijkheyt] of the parts alone.

The passage illustrates Rembrandt’s method in achieving the three-dimensional effect contemporaries so admired in the Night Watch: rough brushwork is applied in the foreground, for instance in the Lieutenant’s uniform, in the drummer and in the Captain’s collar and hand and the paint becomes gradually smoother towards the background.

Van Hoogstraten also refers to “thickness of air”, by which he means that more distant shadows are lighter in tone than those nearby which is also reflected in the Night Watch. “Air,” Van Hoogstraten writes, “forms a body even over a short distance“, meaning that aerial perspective produces tonal differences even when the viewer is closer to the object.

The Italian art historian Filippo Baldinucci, one of Rembrandt’s earliest biographers, never saw the Night Watch in real life. He relied for his 1686 Rembrandt biography on the testimony of the Danish artist Bernhard Keil who, like Van Hoogstraten, was a pupil of Rembrandt in the 1640s and therefore must have known the painting intimately. A passage in Baldinucci’s book is devoted to the foreshortening of the Lieutenant’s partisan (the halberd-like weapon in his left hand) which, Baldinucci says, is so well drawn in perspective that, although upon the picture surface it is no longer than half a braccio, it yet appears to everyone to be seen in its full length. This, he says, the citizens of Amsterdam specifically admired.

The way in which Rembrandt achieved this effect can be seen in the handling of the paint on the partisan’s tassel. He used a lighter blue beyond the point where the blue and white fringe of cords is bound together while over a distance of a few centimeters the paint surface becomes smoother, bringing together Van Hoogstraten’s principles of perceptibility, aerial perspective and the possibility of darker passages advancing further than lighter ones. This is also illustrated in the Captain’s costume which, although black, does not yield ground to the radiant costume of the Lieutenant beside him.

Colour and meaning

A well-known feature of the Night Watch is the shadow of Captain Banninck Cocq’s hand cupping the emblem of the city of Amsterdam embroidered on Lieutenant Willem van Ruytenburch’s coat. This, one learns, is a homage to the city, but there is more in that respect. As Captain of a Kloveniers company, Banninck Cocq should have been wearing a blue sash such as the men in the other civic guards paintings in the hall are wearing. The Captain’s sash, however, is red and combined with his black costume, white cuffs and ruff, his costume represents the colours of the city of Amsterdam; red, white and black. With the Lieutenant in his flamboyant gold-coloured uniform with blue accents (the civic guards colours) next to him the message is clear: the function of the Kloveniers civic guards is to protect the city of Amsterdam.

The coat of arms of the Kloveniers consisted of a golden claw on a blue field and this is acted out not just in the Lieutenant’s uniform but in other parts of the painting as well, for instance in the little girls, one dressed in golden yellow with a light blue cape embroidered with gold, the other, partly hidden by her, in blue, who walk towards the procession to take their places. They are caught in a pool of radiant golden sunlight that illuminates them and the company symbols they are carrying: the precious ceremonial drinking horn and a chicken dangling upside down from the first girl’s belt.

From this detail it already becomes clear how worn the painting is. For more on its condition see below

Weapons in the Night Watch and the myth of rejection

One element in the Night Watch focuses on the civic guards’ exercise of their main weapon, the arquebus or klover. Rembrandt borrowed poses from the then well-known Wapenhandelinghe (the Exercise of Arms) with engravings by Jacob de Gheyn II of 1608. He presented the three most important exercises the civic guards engaged in in logical order from left to right on the painting’s central plane:

1. loading

2. firing

3. blowing residual gunpowder away from the firing pan

This was by no means exceptional: in 1630 Nicolaes Lastman in his civic guards group portrait quoted from the Wapenhandelinghe in the costumes of the sitters and in Werner van de Valckert’s militia portrait one of the men is emphatically pointing at an engraving in the book (see here). In order to draw even more attention to the cleaning of the rifle’s mechanism, Rembrandt sacrificed part of the Lieutenant’s shoulder, the earlier outline of which can still be seen with the naked eye.

Critics have suggested that the depiction of weapons was not rendered correctly in the Night Watch but. Rembrandt was an avid collector of new and old weapons and for a painter of his abilities it would not have been too difficult to render weapons perfectly. I would suggest that in the painting weapons are subservient to the guards’ portraits which in themselves are subservient to the larger picture: the veneration of the historic traditions and current role of the guards, as well as a depiction of their ceremonial function in festive events such as the glorious entry of Marie de’ Medici in 1638.

The supposed inadequate depiction of weapons as well as later criticism regarding the painting’s poor show of realistic portrayal has led to the myth that the painting was rejected by the Kloveniers. There is, however, no evidence of this. On the contrary: in 1659, in two notarial depositions by Jan Pietersen Bronckhorst and Claes van Cruijsbergen, both depicted in the Night Watch, testified that as far as they could recall Rembrandt had received 1600 guilders for the painting. Each sitter paid according to their prominence in the painting. Given the fact that around that period Rembrandt could ask 500 guilders for an individual portrait, the amount seems perhaps rather low although Bernhard Keil’s estimate, as reported to Baldinucci, that Rembrandt received 4000 guilders for it seems very excessive.

The fact that Rembrandt was paid and that the painting would hang in the Great Hall for almost a century speaks against it being rejected. In fact, it was one of the very last paintings to be transferred from the Kloveniers‘ Great Hall to the Town Hall to join the other civic guards portraits that had already been taken there after the civic guards abandoned their headquarters. In addition, Captain Banninck Cocq had at least three much smaller copies painted, one by Lundens and two for his private family album.

Fantasy and reality in costume in the Night Watch

Captain Willem van Ruytenburch van Vlaerdingen, Lord of Purmerland (1600-1652), lawyer, wears spurs and gloves, typical attributes of a cavalryman. Gloves would only be worn on horseback, as soon as the men dismounted they would take them off

The figures capturing the most attention in the Night Watch due to their position in the painting are no doubt Captain Frans Banninck Cocq and Lieutenant Willem van Ruytenburch. The Lieutenant is the only figure in the painting who wears spurs. It is possible that Rembrandt referred to one of the ceremonial functions of the civic guards during important events such as Marie de’ Medici’s visit to Amsterdam: that of mounted escorts. Van Ruytenburch is not mentioned among the ad hoc mounted guard of honour on the occasion of Marie de’ Medici’s glorious entry, nor is he mentioned among the men taking part in the cavalry escort for Queen Maria Henrietta’s entry into the city on 20 May 1642, but it is tempting to think that he, in his splendid cavalry uniform, symbolically represents the mounted civic guards.

More than twenty years later, in 1663, Rembrandt would paint the portrait of the extremely wealthy bachelor Frederick Rihel on horseback. The portrait is thought to commemorate a similar event: Rihel participated in the mounted honour guard on the occasion of the entry into Amsterdam of Mary Stuart and the young William III on 15 June 1660. Even though fashions changed, there are similarities between his and the Lieutenant’s attire.

Another remarkable figure in the Night Watch is the man dressed entirely in a red civilian costume who has been identified as Jan van der Heede, merchant in groceries. Van der Heede would have been 32 years old in 1642. It has been suggested that the middle classes no longer wore red clothes in the early 1640s. Van der Heede’s loose ruff and cuffs without lace, however, were still fashionable in the 1630s and the decorative appliqués at the knees of his breeches were in vogue around 1640. Red was still a popular colour in military and, in consequence, in court circles in The Hague and this in turn was mimicked by the wealthy middle classes. That red is not worn by the other young men in the Night Watch is simply because prosperous citizens of Amsterdam had become so wealthy that they had turned to wearing gold and silver brocades.

Indeed, the Captain wears gold brocade sleeves under his black coat and the man identified as Ensign Visscher Cornelisen, a wealthy merchant who remained a bachelor all his life, wears a silver brocade suit with coloured silk sleeves. Ensign Visscher’s clothes were lovingly kept by his mother. When she died an “oriental chest” was found in her attic containing, among other clothes owned by her son, “a brocade suit” and “a pair of coloured satin sleeves”, while in an oak chest were kept “two white plumes with a crest of black feathers” and “a blue sash with gold lace”. In the painting the Ensign wears the whole outfit, including two white ostrich feathers.

Sergeant Rombout Kemp’s militia accessories, “two white plumes, a black aigrette and a blue sash with gold lace” were also listed in his death inventory. It is thought that the ostrich feathers (the two white plumes) he wears on his hat show the remains of a helmet that had been painted out, but analysis of the painting shows that the feathers were indeed part of the original plume on Kemp’s hat.

In the back row Rembrandt introduced helmets into his painting. He must have decided later that they were too dominant and changed three of them into imaginary hats. Where the helmets remain, they seem to be more or less current types but Rembrandt embellished them with decorative elements such as the hat worn by Sergeant Engelen which comes from Rembrandt’s world of history painting. Engelen also wears a plain cuirass and grasps his antique halberd in his mailed fist. His old-fashioned, broad-striped dark blue sleeves refer to the 16th century, as does the mysterious figure of the extra just to the left behind the Captain. Rembrandt rigged him out in a Spanish or Italian type morion of around 1590 which goes splendidly with his padded purple hose in the outdated Spanish fashion of the previous century, as do his dagger and poniard of a type no longer in use in the 1640s.

The outfits and weapons, contemporary and historic, realistic and fantastic, combined and distributed strategically in the composition make the Night Watch into an elaborate tableaux vivant honouring the company of District II in the present while harking back to the civic guards’ glorious past. In this respect the Night Watch was an innovative painting within 17th century group portraits. It was the painter Johannes Spilbergen who, although modelling his civic guards portrait on Bartholomeus van der Helst’s 1648 piece of the same topic (the banquet celebrating the Peace of Münster) followed this example by introducing a 16th century helmet into his composition as a symbol of the guards’ glorious past and traditions. Spilbergen’s painting was very likely the last large civic guards portrait to be painted in Amsterdam.

Early restoration history and the impact of the 1715 cropping

Although still impressive, the Night Watch has suffered a great deal over the centuries. When the painting was cropped in 1715 to make it fit between two doors, its spatial effect, unity and coherent action were severely compromised. The Captain and Lieutenant now find themselves in the center of the composition whereas they originally stood more towards the right. Because a strip at the bottom was cut off, they seem almost to trip over the frame and tumble out of the painting, which reduces the space around them that is needed to create the illusion of natural movement. Since a large chunk was cut off from the left, the entourage behind them now looks far more chaotically crowded than Rembrandt intended, as a reconstruction of the painting in its original state shows compared with the painting as it is today.

Entries in the city’s 17th century treasury records and Resolution Books tell us that the painting, not yet half a century after leaving Rembrandt’s premises, was subjected to multiple interventions together with the other civic guards paintings that had reverted to the city. Interventions are recorded in 1686, 1687, 1688, 1689 and 1693, and in several entries, for instance that of 1704, there is mention of “holes” in the paintings that needed to be repaired. Once installed in the Town Hall, an entry mentions that during the installation of some benches a hammer was accidentally dropped on the Night Watch, causing a gaping hole in the canvas.

From the mid-18th century onwards, the frequency of the treatments only increased. There are no detailed accounts of these earlier treatments but one Jacob Buys is mentioned as having “overpainted” the Night Watch in 1771, to what extent is unclear. Jan van Dyk, the restorer of the city’s paintings, not only cleaned but presumably also retouched the painting to a larger or lesser extent in 1751 and possibly also relined the canvas in 1761.

In 1781, Sir Joshua Reynolds visited Amsterdam and his assessment of the Night Watch, still located in the Small War Council Chamber in the Town Hall, was a gloomy one:

So far indeed am I of thinking that this last picture deserves its great reputation, that it was with difficulty I could persuade myself that it was painted by Rembrandt; it seemed to me to have more of the yellow manner of Boll [sic]. The name of Rembrandt, however, is certainly upon it, with the date 1642. It appears to have been much damaged, but what remains seems to be painted in a poor manner.

“The yellow manner of Boll” may refer to persistent problems with the varnish that eventually earned the painting the nickname Night Watch. Various methods were tried to remedy these such as regenerating, cleaning, “powdering”, removing and replacing the most problematic areas of varnish and eventually revarnishing the entire painting on several occasions, but after the initial success of each treatment, recorded in jubilant articles, the problems would recur fairly soon: the varnish would become dull and lost its transparency. On several occasions the varnish was regenerated by rubbing it with alcohol or by exposing the painting for long periods to alcoholic vapours, by rubbing the surface with copaiva balsam and other methods, and that at regular intervals throughout the centuries.

The toll of fame

In 1851 restorer Hopman relined the canvas and subjected it to an intensive restoration. In 1914, 1916 and 1921, 1934 and 1936 further regenerations and treatments of the varnish were recorded. Other restorations became necessary due to exceptional circumstances as the elevation of the painting to national symbol on the high altar of art in the Rijksmuseum provoked repeated aggression during the 20th century. On 13 January 1911 an unemployed ship’s cook attacked the Night Watch with a knife but only the varnish was damaged. The knife did not penetrate the paint.

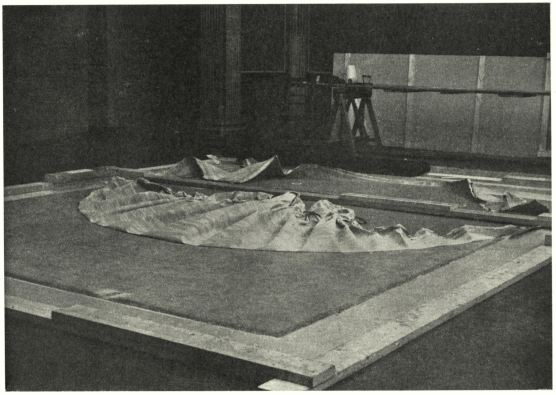

In 1939 the outbreak of the Second World War necessitated evacuation of the Night Watch and other national art treasures. Rembrandt’s painting was initially stored in shelters in the west of the country but early in 1942 these were no longer deemed safe and the painting was transported to the caves in the Sint Pietersberg mountain near Maastricht in the south of the country where a consistent temperature and dry climate ensured the preservation of the paintings stored there. The long journey of the Night Watch across the country was a hazardous one in a time of war: at one time the convoy was forced to spend the night in a farm and the painting, rolled up, spent the night in an open shed in the pouring rain.

Once the Night Watch arrived in the caves, the painting was rolled on a cylinder the handle of which was turned slighty every day to relieve pressure on the paint. In June 1945, shortly after the ending of World War II, the Night Watch finally returned to Amsterdam. It was said that the then director of the Rijksmuseum was so enthousiastic about its return that he tripped and fell flat on the painting, but this has never been confirmed. Remarkably, the painting appeared to be in fairly good condition given its ordeal. The only apparent damage was that the 1851 relining canvas had become loose in some places so that it had to be newly relined. The varnish was once more regenerated.

The worst damage, however, occurred on in September 1975 when an unemployed school teacher managed to savage the painting with a knife before he could be overpowered by the guards. The vicious attack caused severe scratches and cuts, some of which had penetrated the canvas. A triangular piece was completely cut away and had fallen to the floor. Thankfully the area in front of the painting was not immediately wiped clean so that tiny fragments could be retrieved and reused in the intensive restoration that took place in full view of the public. Prior to the dramatic attack it had already been decided to reline the painting again (for the second time in thirty years) and to remove the varnish once more. When it was removed some sixty-eight small holes and tears were discovered that had been repaired in the past, which confirms the early records which frequently mention “holes” in the painting.

On 6 April 1990 the painting was once more attacked, this time with sulphuric acid, but because of the alertness of the museum guards the acid did not penetrate the varnish. Barely a month later, on 1 May of that year, the painting was once more on view.

A chronic patient

It is clear from the historic records and its dramatic recent history that the Night Watch has become a chronic patient. In the past the paint surface has been radically overcleaned, even abraded. This is most clearly visible when looking at the dog which has hardly any paint left on it but it is also possible to see with the naked eye how worn the paint is in other places. Any glazes that would have given the painting its enriching values have long disappeared. The only place where they can still be found is on Captain Bannincq Cocq’s red sash where the red lakes are still intact. The flesh tones are severely worn: in their current condition they consist of only one layer which contrasts with the near-contemporary copy by Gerrit Lundens where it is still possible to see the astonishing richness and variation in flesh tones from one head to another.

The Night Watch‘ long saga of damage, repairs, restorations, revarnishings, relinings and aggressive cleanings reads like the medical file of a chronically ill patient who weakens with every new treatment. The patient has been resuscitated and his life has been prolonged by artificial means, but Rembrandt’s masterpiece is far removed from the glory which filled his contemporaries with such admiration.

Notes

- Dr S.A.C. Dudok van Heel completed the process started by E. Haverkamp-Begemann of identifying the men in the Night Watch. Taking the names written on the shield in the painting and, if listed, their function in the guards, he conducted painstaking research in the Amsterdam Archives and compared the men’s features with other known portraits of them when available.

- All images of the Night Watch courtesy of the Rijksmuseum.

Selected literature

- Samuel van Hoogstraten, Inleyding tot de Hooge Schoole der Schilderkonst, 1678

- A. van Schendel and H.H Mertens, “De restauraties van Rembrandt’s Nachtwacht”, Oud Holland, 1947

- E. van de Wetering (et al), A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, Vol. III, 1989

- S.A.C. Dudok van Heel, “De galerij en schilderloods van Rembrandt of waar schilderde Rembrandt de Nachtwacht”, Maandblad Amstelodamum, 1987

- E. van de Wetering, C.M. Groen and J.A. Mosk, “Summary Report on the Results of the Technical Examination of Rembrandt’s Night Watch”, Bulletin van het Rijksmuseum, 1976

- P.J.J. van Thiel, “The Damaging and Restoration of Rembrandt’s Night Watch”, Bulletin van het Rijksmuseum, 1976

- M. de Winkel, Fashion and Fancy. Dress and Meaning in Rembrandt’s Paintings, 2006

- S.A.C. Dudok van Heel, “Frans Banninck Cocq’s Troop in Rembrandt’s Nightwatch”, Bulletin van het Rijksmuseum, 2009