Karel van Mander (1548-1606), Haarlem painter, poet and author, dedicated a brief chapter to “Italian painters who are currently in Rome” in his Schilder-Boeck (Painter Book). Included is “one Michelangelo da Caravaggio, who is doing marvellous things in Rome.” Van Mander discusses several of these works and also the painter’s views:

He says that all things are mere bagatelles, child’s play or nonsense, no matter what they are or by whom they are painted, if they are not done from life, and that one cannot do better than to imitate nature. He thus does not make one single stroke without being close to nature, copying and painting it. To be sure, this is not a bad way to achieve great results, because painting from drawings (however close they may be to life) is certainly not so trustworthy as having life before one’s eyes and following Nature with all its various colours. Still, one must first have acquired enough insight to be able to distinguish and to choose from life the most beautiful of the beautiful.

The Schilder-Boeck was published in 1604 when Caravaggio was indeed living in Rome. It is remarkable that in far away Haarlem Van Mander was so well-informed about Caravaggio’s art, which he had almost certainly never seen first-hand, that he even sensed the criticism it would encounter. Ten years after Caravaggio’s death in 1610 the Italian art lover Giulio Mancini complained that the painter had chosen as his model for Mary in The Death of the Virgin “one or other filthy whore”. Later in the 17th century Caravaggio was criticised for lacking decorum, that he recognised “no other master than the model and failed to select the best forms in nature”, echoing Van Mander’s criticism that he failed “to distinguish and to choose from life the most beautiful of the beautiful”.

Similar criticism befell Caravaggio’s followers in the Low Countries, one of whom was the Utrecht painter Hendrick ter Brugghen (ca. 1588-1629) who studied under the father of the Utrecht school of painters, Abraham Bloemaert (1566-1651). Ter Brugghen travelled to Italy, possibly as early as 1604 at the early age of sixteen, where he “practised his art for several years” according to his own statement upon his return to Utrecht in 1615. So far no Italian works by Ter Brugghen are known with any certainty (estimates vary between eight and fifteen), which is surprising since both Van Honthorst and Van Baburen, Ter Brugghen’s Utrecht contemporaries who followed him to Italy some years later, received important commissions and earned fame there.

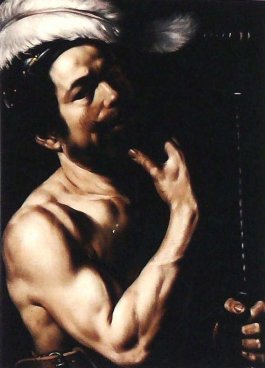

Theoretically Ter Brugghen could have met Caravaggio in Italy although there is no proof of this, but he certainly became influenced by his paintings as well as by those of Caravaggio’s followers Orazio Gentileschi and Bartolommeo Manfredi. Ter Brugghen’s rather nervous style is very recognisable: he would endlessly add fold upon fold in garments, wrinkle upon wrinkle in elderly faces and crease upon crease in paper. A good example is his 1621 St Mark.

The Adoration of the Magi

Ter Brugghen’s Adoration of the Magi was acquired by the London dealers B. Cohen & Sons in 1966 from a country house in Yorkshire. It was thought to be an Italian work and attributed to Domenico Fetti. There appeared to be no signature but it was soon recognised as a Ter Brugghen on stylistic grounds and offered to the Rijksmuseum which acquired it four years later. An X-ray examination revealed that the original composition had been enlarged by the addition of strokes of canvas at the top and bottom to make it vertical whereas Ter Brugghen’s works are typically horizontally oriented. Both these additions were painted at a later period, rather in the style of Isaac de Moucheron (1670-1744), although the alteration could have been carried out in England.

When the strokes of canvas were removed and the painting restored, a signature and date emerged proving that the top and bottom strokes of canvas had been later addition as the signature appeared in a logical spot: at the bottom of the resized canvas to the left of the Virgin’s blue garment. Hard to see with the naked eye, it is visible under the microscope and reads HT- Brugghen fecit 1619. Ter Brugghen rarely dated paintings prior to 1621 (I know of only one earlier dated painting: the Supper at Emmaus in the Toledo Museum of Art), which makes the Adoration of the Magi a welcome addition to his securely dated pre-1621 oeuvre.

The restoration revealed something else that seemed rather strange: the Christ Child sitting on his mother’s lap appeared rather weakly painted in a style that did not correspond with Ter Brugghen’s. It looked like a rather standard cherub-like Christ Child. Perhaps it, too, was a later overpainting. Indeed: further X-rays revealed that under this rather standard baby another baby could be seen: Hendrick Ter Brugghen’s original infant Jesus. Because the original infant appeared to be well preserved, it was decided to remove the overpainting and restore the original Christ Child.

Surprisingly, during restoration the baby began to put on weight. By the time the painting had been fully restored it became obvious that Ter Brugghen had envisaged a very different type of Christ Child from the idealised infant that covered it. He had apparently thoroughly studied the wrinkles and creases of a new-born baby. But the Christ Child’s size and his gesturing arm, outstretched towards the foremost King, make him seem more like a toddler; his pensive, unsmiling face with all its creases and wrinkles even make him look like a little old man. Typically, Ter Brugghen just could not leave the baby’s skin alone, adding wrinkle upon wrinkle, crease upon crease.

One of the painting’s previous owners, at a time when classicist ideals of beauty prevailed, obviously thought that Ter Brugghen had failed miserably at “distinguishing and choosing the most beautiful” and had commissioned someone to replace the original baby with a much more acceptable, “prettier”, Christ Child. As Joachim von Sandrart, writing in 1675, concluded: “[Ter Brugghen] imitated nature and its unhappy shortcomings very well, but disagreeably”.

Today, such early overpaintings are often considered part of the history of a painting and the pretty infant may have been left intact. But in fact the unusual baby is essential for the composition which centers on the Child whose head is at the level of the horizon and marks the vanishing point. The Child is also the lightest point in the painting, even though the play of light illuminates the faces of the Magi and their train and leave those of the Child and his parents in shadow. In this way Ter Brugghen, in a masterly composition, draws the viewer’s attention to the mystery of the first international recognition of the Redeemer.

Note:

A full restoration report on the painting (in Dutch) appeared in the Rijksmuseum Bulletin, 19, 3 (1971), pp. 117-135.