In an earlier post I reported on the recent discovery of 17th century ceiling paintings in the Trippenhuis, the home of the Royal Dutch Academy of Arts and Sciences in Amsterdam. They were hidden behind an early 19th century plaster ceiling and the dilemma arose whether the plaster ceiling should be preserved or whether the 17th century paintings should be uncovered. In order to do the latter, the entire plaster ceiling would have to be removed. A seeming dilemma – but is it? Time to take a closer look. Last week I was able to visit the house which is not normally open to the public and to take photos.

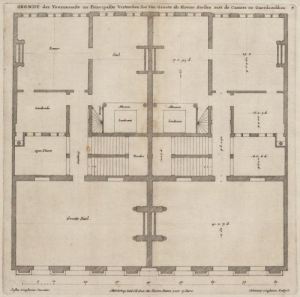

In order to understand the significance of the newly discovered paintings for the decorative programme, one has to understand the layout of the Trippenhuis which consisted of two homes annex offices for the Trip brothers Hendrick and Louys, under one roof. The two homes/offices were strictly separated but were each other’s mirror both in layout and in their decorations. The partition wall between the homes ran straight down the middle which posed a problem since the façade consisted of seven windowed bays allowing, according to classicist principles, for a corridor to run down the center. This, however, was not what the brothers intended. In order to solve the problem architect Justus Vingboons opted for the solution to board up the central façade windows as the partition wall divided these in two. The partition wall was removed when the Rijksmuseum moved into the building in 1815.

Since the Trip brothers made their fortune in the weapons and iron industry, the decorative programme both on the outside and on the inside was devised around the motto Ex bello pax (from war, peace), a firmly held belief at a time when armed conflict was always lurking: the Second Anglo-Dutch war was in fact not far off and the end of the 80 years war with Spain not far behind.

The decorative programme was consistent in both houses, with the distinction that the interior decorations were complementary: while the paintings and decorations in Hendrick’s home expressed the need for good weaponry, the decorations in Louys’ home celebrated peace and prosperity brought about by (successful) war efforts. The uniting theme of both programmes was the Peace of Münster (1648) which had ended the 80 years war with Spain.

Mirrored houses and decorations reflected in ceiling paintings in the rooms. Left: from Hendrick Trip’s house; right: from Louys Trip’s house

It is inevitable that the house was altered over time. That so many of its original decorations survive is due to the fact that it remained in the family until the end of the 18th century, although Elisabeth van Loon (member of the Van Loon family whose house on Keizersgracht is now a museum) extensively altered Louys’ part of the house in 1730. Unfortunately, this meant that the ceiling paintings by Nicolaas de Heldt Stockade in Louys’ main salon have not survived, but we get a good impression of their splendour and quality from Hendrick’s salon where they survived intact.

Hendrick Trip’s former salon with original wooden floor; the paintings originally belonged to the Trips. This room is still known as “Rembrandt Room” as it is here that, from 1815 to 1885, Rembrandt’s “Nightwatch” hung – or rather: stood, in front of the fireplace at the far end (© MD)

In the 17th century the house must have exuded a sumptuous luxuriousness that rightly earned it the name “city palace”. It had gold leather hangings on the walls as well as many paintings and chimney pieces commissioned from Ferdinand Bol and other leading artists of the day, there were elaborate carvings, and this was not limited to the rooms but implemented throughout. In spite of the alterations the house underwent in later times, it still boasts one of the most complete surviving decorative programmes in any Dutch house of the period.

We have seen in my previous post that between 1815 and 1885 the Rijksmuseum shared the premises with the Royal Institute of Sciences, Literature and Fine Arts and that architect Abraham van der Hart had altered the rooms where the museum housed as well as the corridors and passages leading to them. Corridors were fitted with lowered plaster ceilings in the part of the house where the museum was located. Because so much knowledge had been gained concerning the mirrored decorative scheme elsewhere in the building, restorers felt it would be justified to drill holes in the plasterwork to see if there could still be paintings behind them. They discovered bird paintings similar to those in the corridor of the mirror house. The latter, representing Aesop’s fable of the crow and the raven, have meanwhile been restored. It stands to reason that van der Hart’s plaster ceiling hides another bird fable.

Holes drilled into van der Hart’s 1815-17 plaster ceilings reveal 17th century bird paintings (© MD)

An important question to ask is whether the quality of the early 19th century plaster ceilings in any way equals that of the 17th century ceiling paintings that have already been restored in the mirror house. Now that I have been able to assess the situation in situ I would say they do not. The plaster ceilings are in so far a part of the history of the house that they stem from the period when the Rijksmuseum was located here, but is that enough?

17th century proportions complemented by ceiling paintings and Swedish landscape over door by Allaert van Everdingen (Sweden is where the Trip brothers had their canon foundry and weapons factories)

The corridor adapted in 1815-17 by van der Hart. The ceilings are lowered hiding the original top lintels )

There is such a thing as a building’s integrity and historic dignity. Given the well-preserved 17th century proportions of the corridors, the high quality of the 17th century carvings and ceiling paintings and the spatial coherence of the virtually intact concept, van der Hart’s contribution seems negligible, even disruptive, since his lowered ceilings, hiding the original lintels, violate the spatial proportions. The building is best served by removing the plasterwork. Perhaps, by drilling so many holes that it almost appears as if the plaster ceiling cannot be recovered intact, the restorers anticipated this, but this is speculation on my part.

As I write, a decision has not yet been taken. This could have to do with the fact that, should the plaster ceilings be removed, the paintings behind them will have to be restored: a not unimportant cost factor at a time when the government (the owner of the building) has announced ever more cultural budget cuts. It could also be that decisions are delayed simply because two government agencies are involved: the Government Buildings Agency (Rijksgebouwendienst) and the Government Cultural Heritage Agency. Whenever a government agency is involved, a decision-making process is invariably slow and ponderous and here we have two such agencies.

To be no doubt continued.