Rembrandt, the Noctornal Conspiracy of Claudius Civilis, 1661/62 (?), National Museum, Stockholm

Even in its tragically truncated state Rembrandt’s Nocturnal Conspiracy of Claudius Civilis is, to quote the Dutch 19th century poet and painter Jan Veth: “stirring, exciting, overwhelming, astounding”. This is very much the impact the painting has on spectators today but its current museum setting does not really do Rembrandt’s boldest and most ambitious work justice. As we have seen in the previous post, it was painted to be seen from a distance and from below: in its original setting in one of the arches of the Town Hall galleries it hung six meters above floor level.

An impression of a gallery in the Town Hall by Pieter de Hooch, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg. Note the muted wall finishes as opposed to today’s white marble (see previous post)

This setting explains the bold style in which it was painted for as Rembrandt’s pupil Samuel van Hoogstraten (who may very well quote his master) wrote:

You will assuredly regret it if, in paining a piece that has to hang high up, and has to be seen from a distance, you have wasted much time on small details. Don’t hesitate then to take brushes that fill a hand, and let every stroke [of the brush] stand on its own and [let] the colours remain in many places almost unmixed: for the height and thickness of the air will show many things merged together which should [seen closer] stand out separately.

Seeing the painting at eye level today in a museum setting it is clear that this is exactly what Rembrandt has done. The coarse brushwork with its thick impasto, the visual presence of smears of paint applied with palette knife and fingers, the mask-like faces, makes the painting appear almost “modern”.

Mask-like faces

Rembrandt’s commission for the Town Hall

For Rembrandt to secure such a prestigious commission from Amsterdam’s Burgomasters was by no means self-evident. At the time (1660) the city magistrates were less than enchanted with the painter and this had everything to do with his voluntary bankruptcy (cessio bonorum) of 1656. Rembrandt had been involved in some underhanded deals to prevent his creditors from claiming what was due to them which, although perhaps not strictly illegal, had tainted his reputation. In May of 1656, very shortly before the cessio bonorum, he went so far as to sign over the deed of his house on Breestraat (the current Rembrandt House Museum) to his son Titus, ostensibly in fulfilment of his deceased wife Saskia’s will but in fact a transparent attempt to keep the house out of the hands of his creditors. Again, this was not strictly illegal, but it prompted the magistrates to immediately implement new regulations preventing others from doing the same.

Cornelis de Graeff at the time of the Batavian commission (1660) by Artus Quellinus, Rijksmuseum

In addition, Rembrandt had failed to cultivate elite patronage such as the brothers De Graeff (as we have seen, Cornelis de Graeff was the prime mover behind the Batavian series for the town hall). Govert Flinck, for example, had taken great pains in cultivating his relationship with the De Graeffs and this may have been in part why he not only executed two paintings for mantelpieces in the Town Hall but was eventually awarded the commission for the whole Batavian series. But when (as we have seen) Govert Flinck died unexpectedly in February 1660 and the Burgomasters invited several painters to submit sketches for the Batavian series, Rembrandt’s reputation as an artist was apparently still sufficient for him to be considered to paint one painting.

We do not know what fee was offered to Rembrandt for the Claudius Civilis but it stands to reason that he could not demand his customary high prices and that bargaining was out of the question. Flinck would have received 1000 guilders for each of his paintings, Lievens received 1200 guilders for his Brinio; it is therefore likely that Rembrandt’s fee would have been around that course.

Rembrandt’s interpretation of the Nocturnal Conspiracy

Rembrandt, Samson’s Wedding feast, 1638, Gemäldegalerie Dresden

Already in 1641 the Leiden painter Philips Angel in his address on Saint Luke’s Day praised Rembrandt for the careful study and thought he gave to the depiction of history scenes. He singled out Samson’s Wedding Feast (1638) which, he said, was a prime example of how not only a Bible passage (Judges, 14, 10) was translated into paint but the painting also showed that Rembrandt had studied other sources in order to faithfully record how wedding feasts were conducted in the past, for instance by showing the wedding guests reclining, not seated, at the festive table. This “diligent spirit” (kloecke Geest) as Angel called it, had not deserted Rembrandt when he received is brief for the Batavian scene he was to paint for the Town Hall, the crucial start of the Batavian Revolt. His rendition is based on Tacitus’ Histories where it says:

Civilis collected at one of the sacred groves, ostensibly for a banquet, the chiefs of the nation and the boldest spirits of the lower class. When he saw them warmed with the festivities of the night, he began by speaking of the renown and glory of their race, and then counted the wrongs and the oppressions which they endured, and all the other evils of slavery. Having been listened to with great approval, he bound the whole assembly with barbarous rites and the national forms of oath.

“Warming with the festivities”

The text under Tempesta’s print (see below) makes no mention of “barbaric rites” or “national forms of oath”, it merely states that Claudius Civilis “took their oath”. Rembrandt, however, stuck to Tacitus; what Tacitus called barbaro ritu he translated by showing the tribesmen making their oaths by touching their own swords to the wide, uplifted blade held by Civilis who is therefore easily identified as the tall man behind the table. While the others are engaged in the oath, one man on the right, perhaps a “bold spirit of the lower classes”, is happily grinning at the glass in front of him, still in the act of “warming with the festivities”. Elsewhere Tacitus had mentioned the fact that Claudius was blind in one eye and the other Town Hall painters (as Tempesta and others before them) had therefore discretely portrayed him in profile showing the side of his face with the good eye but Rembrandt makes him look at us directly so that his disfigurement clearly shows. With his rough appearance and strange ornate hat Rembrandt’s Claudius looks for all the world like a barbaric warlord.

Rembrandt originally used dark blue pigments such as in the hat and some of the gowns. Because he used the cheaper smalt (as opposed to the expensive lapis lazuli, used a.o. by Vermeer) these blues have faded over time

The composition

The scene depicted is nocturnal but it is still possible to see the events evolve thanks to a light source hidden behind one of the figures in front of the table as well as light powerfully reflected from the white table-cloth which is sufficient to illuminate all the figures more or less strongly from below. Rembrandt must have kept in mind how high his painting was to hang in a (as we have seen) rather dim corner and by implementing these light sources, how the legibility of the scene could be enhanced.

Rembrandt. The Conspiracy of the Batavians under Claudius Civilis (recto). Pen and pencil, brown ink on paper, 19,6 x 18 cm. Staatliche Grafische Sammlung, München, Germany

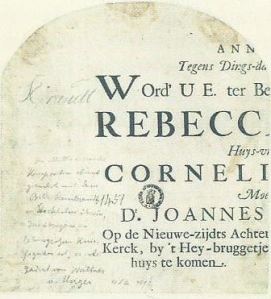

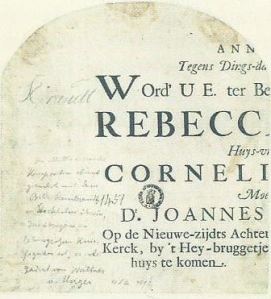

Very interesting is a drawing that is in itself an unusual document as it is sketched on the back of a funeral card. The text on the card has not survived completely but another copy was found among the papers of notary Sebastiaan van der Piet so that it could be reconstructed. It reads that on Tuesday 25 October 1661:

Munich drawing verso

You are asked to attend the funeral of

REBECCA DE VOS

Wife of

CORNELIS BETH

Mother of

DR JOANNES GUALTHERUS

at the Nieuwe-zijdts Achter Burgwal near the Lutheran

Church, at the Hey-bruggetje at 10 o’clock. As a friend

of the house; come!

The rectangle shows approximately how drastically the original painting was cut down.

Long believed to have been a preparatory drawing, the Munich drawing is now thought to show how the painter saw the composition at a certain stage of the creative process. For instance, in the drawing the table is shorter on the left than in the finished painting and Claudius is seen standing next to it whereas in the painting he is stationed behind it. Rembrandt must have realised that to offset Claudius as the central figure of the group he needed the light source coming from the white tablecloth and therefore extended the table to the left, thereby transferring the oath swearing with swords from taking place next to the table to the table itself in the painting. In the drawing it looks as if the figures on the sides were enlarged and that the steps receded into the vast space which must have given the painting an astounding sense of perspective and depth especially when viewed from below. But most startling of all, comparing the painting today with the work drawing, is the realisation that two-thirds of the painting is missing.

What happened?

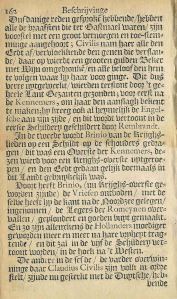

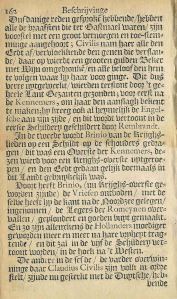

The relevant page from Fokkens’ 1662 book, Special Collections Library, University of Amsterdam

We know that Rembrandt’s majestic Claudius Civilis once did hang in the Town Hall, next to Lievens’ Brinio, thanks to a description of Amsterdam, a 17th century Baedeker, published by M. Fokkens in July 1662. After elaborately describing the story, Fokkens ends his paragraph: “and this is depicted in the first painting [of the series] by Rembrandt”. But by the time the Archbishop and Elector of Cologne visited the city, 24 September 1662, Flinck’s sketch of the scene, worked up by Jürgen Ovens, had replaced Rembrandt’s masterpiece as we have seen in the previous post. It is impossible to know with certainty why Rembrandt’s canvas was taken down and not reinstated. I let follow a few theories and leave you to decide which is the most plausible.

1. The contract with Van Ludick

One clue might come from a contract Rembrandt concluded on 28 August 1662 with one of his most persistent creditors, Lodewijk van Ludick. According to the third stipulation in the contract Rembrandt promised “that Van Ludick shall be entitled to one-quarter of all that the aforementioned van Rhijn shall gain from the painting delivered to the town hall, and as much as he, van Rhijn, may claim should he further profit from altering that painting, or otherwise benefit in whatever way.” This has been taken to mean that the painting had already been taken down for Rembrandt to implement changes, but this need not be so since the operative word is “should”. In any case, Rembrandt was highly optimistic in thinking that, should any alterations be demanded, he would get paid for them as it appears that the painters involved in the project received one agreed fee for their work and not a guilder more. There is the example where the painter Jan van Bronckhorst, who had had to alter his painting for another room in the Town Hall, received less than the agreed fee on account of having to adapt it. Since Rembrandt’s work was never reinstated it could well be that he did not get paid at all.

2. Objections to contents

Tempesta’s Conspiracy of Claudius Civilis, 1612, Rijksmuseum

Did the Burgomasters object to the contents of the painting and did it therefore have to come down? In style and “decorum” it was certainly vastly different from the other paintings in the Batavian series. After all, Claudius Civilis was seen as the prefiguration of William of Orange who initiated the revolt that led to the liberation of the seven Dutch Provinces from Spanish oppression. Rembrandt’s hero does not conform to the pictorial tradition shown in Tempesta’s print (above) in which the Batavians courteously shake hands to seal their alliance against the Romans. Instead, here was a ruffian with an ugly blind eye and not the civilised leader the church-going Protestant Amsterdam burghers could mirror themselves on. Moreover, the raising of the swords, the mysterious chalice raised, may have looked to them “barbaric”. Had Rembrandt taken Tacitus too literally? But why then had the Burgomasters waited until the painting was put up in the arch? Had they not seen it when it was first brought into the Town Hall?

3. Depressed versus semi-circular arches

Another theory, first opted by A. Noack, suggests that Rembrandt’s drawing is rounded off above with a depressed arch whereas the arch in which the painting was to be hung is semi-circular. In Jacob van Campen’s original design for the Town Hall the lunettes were indeed topped by depressed arches but when the design of the gallery was altered by Daniël Stalpaert, these became semi-circular. Noack suggests that Rembrandt may have based his painting on the wrong construction drawing. Interesting, but unlikely. It was customary that artists participating in such commissions were provided with primed canvases – surely Rembrandt would have received the correct size and shape of canvas.

Depressed arch in Rembrandt’s drawing as in Van Campen’s original design

The final design by Stalpaert: semi-circular arches

4. Stylistic clashes with the other paintings in the series

The composition of the other paintings of the Batavian series is pyramidal (see previous post for examples) and the figures fill the canvases whereas Rembrandt’s figures are arranged more or less on the central horizontal plane. Most of the space is taken up by the vast open hall and the forest which can be glimpsed through its arches which would have harmonised well with the then sandstone coloured surrounds, making the painting an integral part of the architecture of the gallery so that the figures in it seem to be actors in a vast theatrical setting. But given the vast architecture in the painting, the figures may have been deemed too small to be seen from a distance. By comparison some of Jordaens’ figures are almost three meters high. There may also have been objections to Rembrandt’s coarse style which contrasts with the more refined classicist paintings by Lievens and Jordaens.

5. Water damage

A reason for the painting’s removal that has not been considered may have been the persistent problems with damp and leakages. A slate roof had been planned but was not put in until 1662. Before that (from 1659) tiles were provisionally used. This inadequate protection caused serious problems of damp in the walls which must also have affected the canvases and indeed during the last restoration of the paintings water damage was clearly visible in all the canvases except Jordaens David and Goliath which dates from after the final slate roofing. Was the damage to Rembrandt’s Claudius Civilis so great that it had to come down even if the painting had hung in the gallery only briefly (anywhere between 25 October 1661, the date on the funeral card, and several days prior to the visit of the Archbishop of Cologne on 24 September 1662)?

6. Rembrandt’s stubbornness

If the painting had come down to be altered – for whatever reason – soon after the publication of Fokkens’ book in July 1662 or around the contract with Van Ludick in August, the Burgomasters were on a tight schedule since the visit of the Archbishop and Elector of Cologne was expected in September. If Rembrandt had begun negotiations over the price for these alterations as the Van Ludick contract may suggest (which in any case was useless as we have seen) there may have been more delay than the Burgomasters could afford and moreover, by failing to cultivate important patrons, the artist did not have enough supporters in the right places when obstacles such as this arose. In that same year he was also engaged in painting his masterpiece The Syndics and he was not one who liked to be pressured as we have seen in the story about his Genoese commission.

From Amsterdam to Sweden

Cosimo ca. 1665 by Justus Sustermans, Palazzo Pitti (detail)

Whatever happened, down Claudius Civilis came and it was not returned to its niche in the gallery. In all likelihood it was Rembrandt himself who cut the painting down to its present size possibly in the hope that he could still sell the central fragment. It is assumed that he kept the painting in his studio on Rozengracht until is death in 1669 but when the future Cosimo de’ Medici III, on the morning of 29th December 1667, knocked on Rembrandt’s door the Florentine’s journal records that the painter had no finished works to show. But Rembrandt possibly still had the Claudius Civilis and he was not one to turn down a client when the opportunity arose to sell a painting. Did he no longer have it? Or was he still in the process of revising it? X-rays made in Stockholm in 1956 have shown that, for example, the face of the person sitting behind the table was subsequently overpainted with the figure standing with his back towards it on our side of the table. These changes may well have been implemented during the creation process but they also could have occurred after the painting was reduced to its present size.

Be it as it may, on 25 August 1798 a wealthy Swedish widow bequeathed a large painting to the Swedish Royal Academy of the Arts in Stockholm. Tradition in her family had it that the work was by Rembrandt and that it depicted a scene taken from Czech history (The solemn oath between Jan Zizka, Leader of the Hussites and the Calixtines, to defend and preserve the eucharist).

Rembrandt’s Claudius Civilis shown in the painting “Gustav III’s visit to the Royal Academy of Arts”, 1782, by Elias Martin, National Museum Stockholm

A treasure hunt at Amsterdam’s Royal Palace

Almost a century later, in 1891, the Amsterdam archivist Nicolaes de Roever discovered that Rembrandt had produced a large painting for the Amsterdam Town Hall showing the nocturnal meal of Claudius Civilis and the Batavians, something that had until then escaped notice. De Roever suspected that the painting may still be in the building on Dam Square, which in the mean time had become the Royal Palace, and sought and obtained royal permission to try to find it. On 18 March 1892 De Roever, together with a number of interested parties, searched the building, but they found nothing. Present at the search was Karl Madsen, Danish art historian and Rembrandt expert. Madsen had come to suspect that, based on De Roever’s archival discovery, the fragment in Sweden may be none other than the lost Claudius Civilis. He subsequently connected the fragment with the drawing in Munich which had until then been thought to represent Christ’s circumcision. The painting is now on permanent loan to the Stockholm National Museum and has come to the Rijksmuseum during the Stockholm museum’s refurbishments, possibly (hopefully) until 2018.

What happened to the two-thirds of the painting that had been ruthlessly cut off? Since canvas was expensive in the 17th century it is quite possible that it was reused, either by Rembrandt or by other painter(s). With advancing technology it may be possible in the future to identify the lost strips of canvas from the Claudius Civilis.

What might have been

In 2011 the Royal Palace organised an exhibition on the paintings for the Batavian series on the occasion of their recent restoration. As part of the exhibition a projection was made of what Rembrandt’s masterpiece would have looked like hanging in the galleries. Compiled of the fragment in Stockholm and the Munich drawing, it gave an impression – albeit a faint one – of how that majestic painting would have looked in July 1662 when Fokkens saw it.

Selected sources:

Selected sources:

- M. Fokkens, Beschrijvinge der wijdt vermaarde Koop-Stadt Amsterdam, 1662.

- N. de Roever, “Een Rembrandt op ‘t stadhuis”, Oud Holland, 1891.

- I.H. van Eeghen, “Rembrandt’s Claudius Civilis and the funeral ticket”, Konsthistorisk Tidskrift, vol. 25, 1956.

- Seymour Slive, Rembrandt and his Critics, 1630-1730, 1953.

- Paul Crenshaw, Rembrandt’s Bankruptcy, 2006.