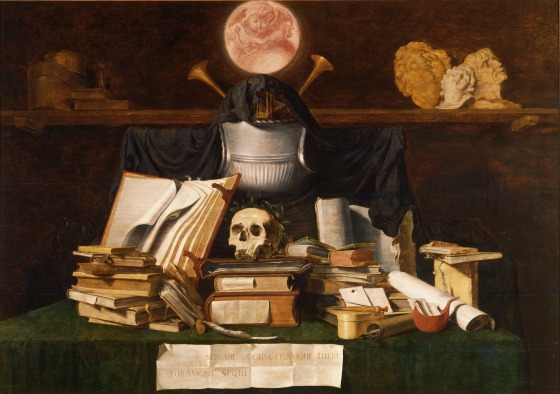

The excessive contemporary praise lavished on the still life paintings of Johannes Torrentius (1589-1644) led to irritation among his colleagues to such an extent that Constantijn Huygens’ close friend, the established artist and still life specialist Jacques de Gheyn (1565-1629), felt provoked into challenging Torrentius to a contest in painting skills. The painting De Gheyn offered for comparison has been identified as the large Vanitas Still Life dated 1621. Which painting Torrentius contributed is not known.

Jacques de Gheyn (II), Vanitas Still Life, 1621, Oil on panel, 117.5 x 165.4cm (46 1/4 x 65 1/8in.), Yale University Art Gallery

Who won? Huygens is diplomatic about the outcome, saying he did not see the two paintings together. He does say that there was nothing in De Gheyn’s manner and method that could not be recognised by connoisseurs. In other words: there was nothing supernatural in De Gheyn’s art, whereas Torrentius “tires the doubtful minds, as they are searching in vain, in what manner he used colours, oil and – if the Gods may wish – also brushes.” And a camera obscura?

Huygens’ suspicions

Poet, composer, architect, scientist and diplomat Constantijn Huygens (1596-1687) had a keen interest in the artistic and scientific developments of his day and counted several painters among his close friends. In 1622 he purchased a camera obscura from Cornelis Drebbel, a Dutch inventor who had settled in London. Back home, Huygens enthusiastically demonstrated his new camera to his painter friends and one day Torrentius “accompanied by several men of standing” urgently asked to see him. Huygens’ account of this visit is worth quoting in full:

[Torrentius’] excuse was that he wanted to see my optical instrument [Drebbel’s camera] with which in a closed space on a white surface one can project the contours of things that are outside the room. Torrentius, who displayed his usual submissive modesty and polite manners, looked with feigned amazement at the dancing figures and asked if these little people he saw were actually present as living creatures outside the room. I confirmed this. As soon as my friends left I remembered his naive question and his feigned ignorance concerning something everyone knows about these days. I suspected that he was very well aware of the invention but had wanted to create the impression that he was not.

It is quite possible that Torrentius heard of Huygens’ new camera and was anxious to ascertain whether it offered new possibilities as the camera obscuras of the early 17th century were still rather primitive. Could Torrentius’ desire to keep the secrets of his painting methods to himself be the reason why his studio was apparently in his attic? An attic would have the added advantage that the influx of incoming light was limited and could easily be controlled which was essential for camera obscura projections. His secretiveness could also explain Torrentius’ insistence that he used extremely toxic, even “explosive” paints which would keep the curious at bay. As discussed in the previous post his paints were, after all, rather conventional.

Still life versus figure paintings

The uncertainty about his methods contributed to another myth which Torrentius apparently was keen to perpetuate and which, in Huygens’ words, ran among his “uncritical followers”: that “in a moment of divine ecstasy he was suddenly blessed with the gift of this unknown art.” But, Huygens continues, if this was indeed a divine gift, something must have gone very wrong concerning the most important aspect of it: Torrentius’ rendering of human figures and other living creatures “for which one would expect the same appreciation as for his other work” was “so shamelessly primitive that connoisseurs hardly consider them worth a glance.” The painter Joachim von Sandrart in his Teutsche Academie (1675-80) more or less confirms this: “Apart from these still life paintings I have not seen anything special from him.” How weak a draughtsman Torrentius was is confirmed by the drawing in Weimar – if in fact it is his.

The discrepancy in the rendering of different subjects also seems to confirm that Torrentius used a mechanical device, most probably a camera obscura, for his exceptional still lifes. Given the limitations of the 17th century camera a projection of a live model would have to be finished in one single session. After a break in that session it would be impossible to recreate the same situation, whereas a still life set-up remains the same over several sessions.

An experiment

In 2006 Torrentius Emblematic Still Life was subjected to an experiment. Could a painting be made using the lenses available in the 17th century? First a small portable camera was used, most likely dating from the 17th century. The results were then compared with observations using a camera probably dating from the 18th century.

Reconstruction of Torrentius’ still life, set-up in front of an old camera obscura. Image: Max Planck Institute

17th century lenses still had various shortcomings: straight lines projected with them become slightly curved at the edges of the image. Examination of the painting with infrared reflectography revealed lines drawn along a straightedge or ruler under the paint layers. Torrentius’ adjustments to his underdrawing to compensate for the distortions supports the theory that he used a camera obscura.

The most essential features of Torrentius’ painting, the highlights on the flagon and the jug, are remarkably soft and blend smoothly with the darker tones while the highlights on the glass have a “soft focus” appearance corresponding to another limitation imposed by 17th century lenses: light coming from the side and hitting the curvature of the lens at an angle would reduce contrast and definition and would also cause a lack of sharpness which is most prominent in lighter coloured areas or in highlights on darker objects. The reconstructed camera obscura image and Torrentius’ painting share similar features: an intensified rendering of light and dark with brilliant highlights and rich shadows also noticed by Huygens and De Gheyn:

This suspicion [that Torrentius used a camera obscura for his still life paintings] is so far confirmed by the close similarity of Torrentius’ painting with these shadows, as well as by the “undisprovable, the certitude” which is attributed to him, of his art compared with the real shape of the objects about which all spectators agree in every respect.

The image of the still life reconstruction as projected by the camera obscura. Image: Max Planck Institute

Given the instrument’s limited depth of field, it is interesting that all objects in the Emblematic Still Life are placed in a row on the same focal plane. At the same time, since images projected by the camera obscura are circular, a circular (as in the case of Torrentius’ Emblematic Still Life) or a square panel would make the most efficient use of the image projected by it. Round panels were extremely rarely used for Dutch still life paintings from the first half of the 17th century: I know of only five or six other examples.

The search for other paintings by Torrentius

There is every reason to believe, with Huygens, that Torrentius used a camera obscura. It would be interesting to be able to compare the Emblematic Still Life with other still life paintings by Torrentius. His paintings were thought to have been confiscated at the time of his trial and subsequently destroyed. There is, however, no evidence for this. A list drafted in September 1627 by the Haarlem authorities mentions nine paintings, of which four (pornographic) paintings were seized by the schout (sheriff). Seven paintings are listed in the English King Charles I’s State Papers: “Of Torentius Pictures There be at friends house, lyes in Liss(e) neer Leyden, 7 pieces” which is followed by a rather curious note: “His other bawdye pictures such as his friends saye he intended should never be seen are to be seen in the town house at Harlem.” At least one of the paintings in Lisse, our Emblematic Still Life, found its way into Charles I’s collection since his brand is on the back of the panel. At least one other painting “by Torrentius given to the King by Lord Dorchester” was auctioned in 1649.

In 1893, the eminent art historian Hofstede de Groot visited the art gallery of Dundee. A still life painting there attributed to a “William Torres”, he thought, could very well be a Torrentius but upon inspection he concluded that it must be by an 18th century Heda follower.

Van Gelder reconstructed Torrentius oeuvre in 1940. He lists twenty-four paintings, nine of which are still lifes. Apart from the Haarlem and Charles I lists, several paintings are mentioned in late 17th and 18th century inventories and (mostly English) auction catalogues as late as 1928. It is likely that some of these and other still unknown or misattributed works still exist, languishing in a private collection somewhere, most likely in the United Kingdom or in Sweden since a 17th century Swedish envoy to the Netherlands is known to have owned Torrentius paintings. Perhaps, as in the case of the Emblematic Still Life accidentally discovered in Enschede, some day someone will strike gold.

Notes:

In recent years paintings have been attributed to Torrentius on anecdotal (Rosicrancianism for instance) rather than art historical grounds. They do not convince and I therefore have not included them in this post.

In addition to (selected) sources mentioned in the previous two posts on Torrentius:

- Wolfgang Lefèvre (ed.), Inside the Camera Obscura – Optics and Art under the Spell of the Projected Image, Max Planck Institute, 2007.

- J.G. van Gelder, “Johannes Torrentius (1589-1644)”, Oud Holland, 1940.

- G. Thiere, Cornelis Drebbel (1577-1633) (dissertation Leiden University), 1932.

- C. Hofstede de Groot, “Hollandsche Kunst in Schotland”, Oud Holland, 1893.

- Joachim von Sandrart, Teutsche Academie der Edlen Bau-, Bild- und Mahlerey-Künste, 1675-80.