In his Life of Raphael Giorgio Vasari movingly recounts the events immediately following Raphael Santi’s death in 1520:

As he lay dead in the hall where he had been working they placed at his head the picture of the Transfiguration which he had done for Cardinal de’ Medici; and the sight of this living work of art along with his dead body made the hearts of everyone who saw it burst with sorrow.

Vasari does not mention in how far the Transfiguration, Raphael’s last and perhaps most puzzling composition, was completed when the artist died. Until the painting was cleaned in 1972-76, scholars limited Raphael’s participation to the left lower group and attributed the right lower group and the upper section to Giulio Romano and Giovanni Francesco Penni respectively. The cleaning confirmed that the majority of the work was by Raphael and that assistants finished only the group at the lower right.

The painting presents two consecutive yet distinct narratives as recounted in the Gospels of Matthew and Mark. The upper register shows a radiant Christ who, with the prophets Elijah and Moses, appears in glory before the apostles Peter, James and John. In the lower register the other apostles (seen left) meet the family of a boy possessed (seen right) but in spite of the frantic pleas of the child’s family they fail to cure him. Their failure is not mentioned as such in the biblical text but is implied in the words of the boy’s father, who addresses Christ after he descended from the mountain: “And I brought him to your disciples and they could not cure him.” The meaning of the painting is perhaps most economically and eloquently expressed by Goethe:

The two are one: below suffering, need, above, effective power, succour. Each bearing on the other, both interacting with one another.

The kneeling female figure in Raphael’s Transfiguration – form and function

In his description of the painting which he termed Raphael’s “most beautiful and most divine work” Vasari somewhat unexpectedly refers to the kneeling female figure in the center foreground as “the principal figure in that panel.”

With her back to the viewer she kneels in a twisted contrapposto pose: her right knee forward and right shoulder back, left knee positioned slightly behind the right and her left shoulder forward, arms directed to the right and her face turned to the left. She offers a structural and compositional bridge between the family group gathered around the possessed boy on the right and the nine apostles on the left. Her spatial and tonal isolation from the surrounding figures and their apparent obliviousness to her stunning presence suggest that we should interpret this figure as different from the others. Jacob Burckhardt (1855) suggested that “the woman lamenting on her knees in front is as it were a reflection of the whole incident.”

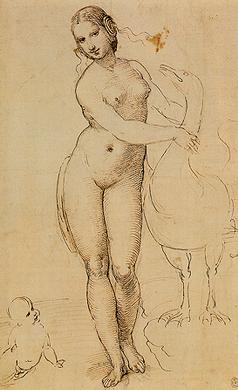

The kneeling woman is Raphael’s most striking depiction of the figura serpentina (serpentine figure). Leonardo developed one of the earliest and most influential expressions of the serpentine figure in his now lost Leda, ca. 1504, which Raphael copied in a drawing upon his arrival in Florence.

Leonardo’s Leda assumes the serpentine pose by drawing her right arm across her chest, which then generates the opposing shift forward in her right hip and leg and the backward shift right. In a similar way Raphael’s female figure in the Transfiguration draws her left arm across her chest and brings her left shoulder forward while her head twists to the left.

Raphael altered the concept of the figura serpentina by including it in multi-figure narratives. In the Vatican Stanza d’Eliodoro, for example, in the fresco of the Expulsion of Heliodorus (1512), a woman is seen who is part of a group of bereft widows and who assumes a pose strikingly similar to that of the female figure in the Transfiguration. The latter, while not actively part of the group of apostles on the left nor of the group of frantic family members on the right, nevertheless intervenes in the narrative in that she bridges the two groups by directing the attention of the apostles to the sick boy. To the 16th century viewer of the altarpiece the importance of her role would have been apparent: her beauty suggests that she represents the manifestation on earth of the radiant Christ seen in the upper register. She thereby emphasises the message that the apostles fail to see the sick boy as a test of their faith which prevents them from being able to heal him.

Developing the image in the composition

As the earliest of the modelli from the studio that represent various stages in the Transfiguration Oberhuber identified a drawing that limits itself to the scene of the Transfiguration on the mountain, here taking place on a small hill.

In this drawing the figure of the apostle kneeling in the foreground already suggests a figure pointing with both arms, although he is relegated to what would become the scene in the upper register of the painting. A later drawing attributed to Raphael’s assistant Giovanni Francesco Penni shows the scene with the possessed boy incorporated in the composition and the figure of a kneeling female figure in the foreground, pointing emphatically at the possessed child.

Weighed down by many and diverse commissions during the last years of his life, Raphael instructed and guided his assistants by providing detailed studies of several important figures, faces and hands in the composition. In order to clarify the figures’ postures and the various ways in which they are to be lit, full figures were shown naked.

Although no autograph compositional studies incorporating the kneeling woman survive, the third drawing, attributed to Rapahel’s studio, nevertheless provides an insight into what the artist envisaged. Here, the woman’s classical form has taken shape and, unlike in the second drawing, she communicates directly with one of the apostles as she does in the painting. The position of her right arm is already that of the painting, that of the left arm would undergo further changes as can also be seen in the Amsterdam drawing.

The Amsterdam drawing

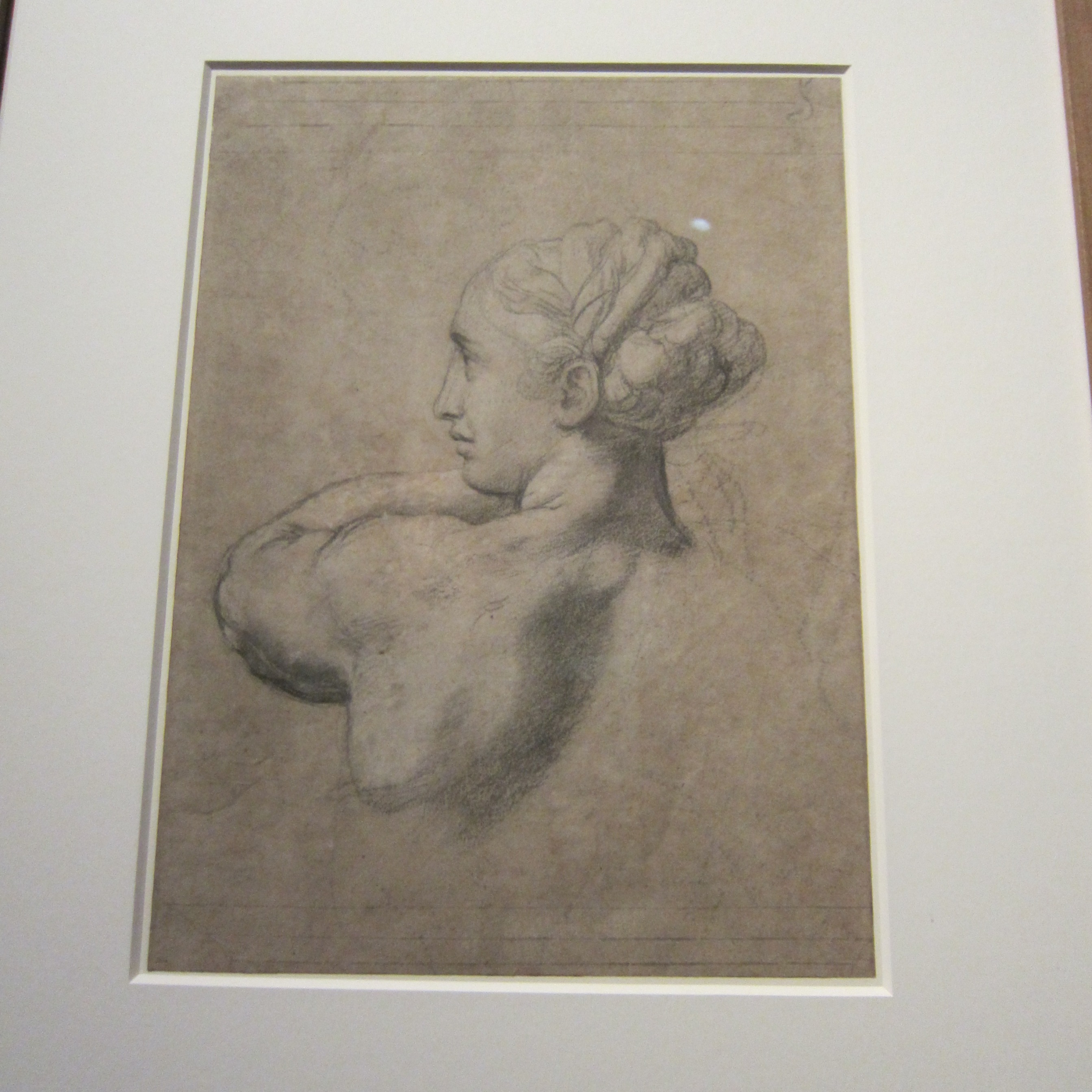

Raphael Santi, Study for the Transfiguration, 1519-20, black and white crayon on grey-brown paper, Rijksmuseum

The Amsterdam drawing is executed in black crayon and there are traces of punched contours visible, for instance on the forehead and cheeks and the facial contours have been repeatedly corrected. The woman’s classical profile and muscular shoulder epitomise Raphael’s search for idealised feminine beauty. Because her arm crosses her face at a lower point, her profile is more pronounced than that of the woman in the painting. The drawing’s strong shadow parts were created with very fine parallel hatching and there are remnants of white highlights that contribute to the strong plasticity of the image. Her expression is softer, gentler than that of the kneeling woman in the painting: it seems to express sadness but also anticipation unlike the determined and intently burning gaze of her painted counterpart.

The function of the Amsterdam drawing is somewhat puzzling in that, in spite of the punch marks, the head in the drawing is not the same size as that of the woman in the painting, which makes it unlikely that it is a fragment of a cartoon (full-size preparatory design for an artwork in another medium). This she has in common with, for instance, the famous drawing of the head of Pope Leo X. The latter has had a rocky reception with authorship passing from Michelangelo to Sebastiano del Piombo to Giulio Romano to Raphael. Likewise, based upon the misconception that the figure in the painting was not by Raphael, the drawing in Amsterdam has at one time been attributed to Raphael’s assistant Giulio Romano but it has later been accepted as an autograph Raphael drawing by such authorities as Oberhuber and Shearman.

Travels of a drawing

The first collectors’ mark on the Amsterdam drawing is that of the painter and collector Sir Thomas Lawrence who died in 1830. The first public auction in which the drawing featured was that of the Dutch King Willem II, held in The Hague in 1850. In the intervening years a peculiar chain of events occurred. Thomas Lawrence stipulated in his will that his collection of Old Master Drawings should be offered to the British nation. His friend, the successful art dealer Samuel Woodburn, set out to fulfil this wish but the mission became something of a curse as Woodburn was unable to sell the collection en bloc to the nation. In order to win over public opinion Woodburn organised ten exhibitions of the best works in the collection: the Ninth Exhibition, held in 1836, contained as many as a hundred drawings then attributed to Raphael.

King Willem II in his private art gallery, Jan van der Hulst, 1848, Historic Collection of the House of Orange-Nassau, The Hague

Private collectors were quicker to act than British public collections and what Woodburn had tried to prevent happened eventually in 1838 when the avid art collector, the Dutch Prince of Orange (the later King Willem II), bought fifty-two of the one hundred Raphael drawings that were on offer in the Ninth Exhibition, among which the Amsterdam drawing. When Willem II died unexpectedly in 1849 it was discovered that his art collecting habits had led him to accumulate huge debts and in order to redress this his art collection was hastily auctioned off in 1850. In part due to the lack of Dutch expertise on Italian art precious paintings and drawings were sold for a fraction of their worth. At the The Hague auction Woodburn bought back thirty-five of the eighty-four Raphael drawings on offer including the drawing now in the Rijksmuseum, featured as “No. 75, Étude de Jeune femme, largement exécutée, à la Pierre d’Italie.”

Via the British Gritton, Newton and Robinson collections the drawing returned to the Netherlands to be included into the impressive drawings collection of Prof. Dr. van Regteren Altena, former director of the Prints and Drawings Department of the Rijksmuseum. In 1971 Van Regteren Altena generously donated the drawing to the Rijksmuseum, making it the only Raphael study of its kind in the museum’s collection.

Photograph taken by me in the Rijksmuseum on 14 January 2014, with Hasan Niyazi very much in my mind

Selected sources:

- Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects, English edition 1996.

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Italienische Reise, first published 1787.

- O. Fischel, “Raphael’s Auxiliary Cartoons”, The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, 1937.

- K. Oberhuber, “Vorzeichnungen zu Raffaels ‘Transfiguration.”‘ Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen, 1962.

- L.C.J. Frerichs, “Een studie voor Rafaëls ‘Transfiguratie’ voor het Rijksprentenkabinet”, Bulletin van het Rijksmuseum, 1971.

- D. Rosand, “Raphael Drawings Revisited”, Master Drawings, 1988.