This post is dedicated to the memory of Hasan Niyazi, Italian Renaissance and especially Raphael scholar, art blogger and passionate advocate of making art available online for everyone. Hasan passed away unexpectedly at the far too early age of 38, almost the same age as Raphael who died at the age of 37, the artist whose art he loved and researched tirelessly. Hasan’s legacy will live on and his generosity and kindness as well as his special gift of communication will be remembered fondly by many.

—

9 April 1639. The atmosphere in the Keizersgracht house must have been electrifying as Lucas van Uffelen’s collection was auctioned. In today’s terms we would call it the “sale of the century”. Van Uffelen, a rich merchant who had lived in Venice from 1615 until the 1630s, had returned to Amsterdam where he had died some time before 10 May 1638 and now his art collection was to be sold from his house at the corner of Westermarkt (Keizersgracht 198, now demolished). We do not know the exact nature of the paintings offered on that day save a few names that have come down to us. Unfortunately the Orphan Chamber’s notebooks, one of the greatest resources for art at auction in the 17th century, have not been preserved after 1638. Had there been just one more such notebook it would have comprised Van Uffelen’s sale, the most important one in the first forty years of the 17th century. The total proceeds of 59,496 guilders comprises an incredible 60% of the total value of the works of art extracted from the Orphan Chamber notebooks during the entire period 1597 to 1638.

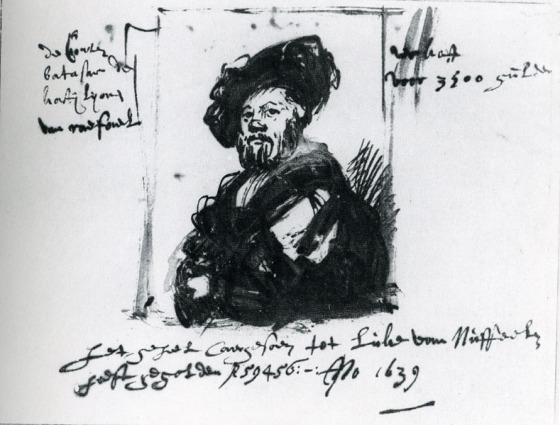

We know about the proceeds from none other than Rembrandt who was present at the sale, but whether he bought anything is unclear. The most significant item offered that day was Raphael’s 1515 portrait of Baldassare Castiglione, the author of the Book of the Courtier (l Libro del Cortegiano). We do not know whether Rembrandt sketched the portrait in situ or, perhaps more likely, whether he sketched it immediately after he got home, from memory. Given how many drawings must have been lost (thrown out by the painter himself or later destroyed), the little sketch must have been of significance to him. It is inscribed: “de Conten batasar de kastijlijone van raefael – verkoft voor 3500 gulden – het geheel caergesoen tot Luke van Nuffelen heeft gegolden f59456:- Ao 1639 (Count Balthasar de Castiglione by Raphael, sold for 3500 guilders. The entire shipment fetched 59,456 guilders at Luke van Nuffelen. Anno 1639). It looks as if he added “Anno 1639” somewhat later, as if to mark the occasion on which he saw the portrait.

The term caergesoen, shipment, seems to indicate that the paintings had been recently transported by ship from Venice to Amsterdam, although it can also mean a collection or possessions in a more general sense. If had been a shipment, the auctioneer would have been the widow De Vos who had acquired the sole concession to auctioneer shipping cargoes. At the Van Uffelen auction, however, the auctioneer was Pieter Haringh, a member of the Haringh family who were important figures in the Amsterdam auction world.

The sum of 3500 guilders for the Raphael was equal to almost five times the value of the most expensive work of art sold in the previous 41 years (an album of prints or drawings by Lucas van Leyden). There were two persistent bidders that we know of: the German painter Joachim von Sandrart, who later mentioned it in his book Academie der Bau-, Bild- und Mahlerey-Künst and Alphonso Lopez, an art dealer and jeweler who was acting upon instructions of Cardinal Richelieu for the French crown. Both were living in Amsterdam at the time. Lopez, ostensibly in Amsterdam to buy war materials, resided in a large house called De Vergulde Zon (the gilt sun) on the Singel (now number 118, still called De Zon (The Sun) today). He had an extensive art collection which included Titian’s so-called portrait of the poet Ariosto and his Flora but also Rembrandt’s own early painting Balaam and the Ass (1626). Von Sandrart tells us that he himself did not want to spend more than 3400 guilders for the Raphael so that after what may have been a hectic bidding session, Lopez secured the Raphael and took the painting with him to France when he left Amsterdam in 1640. It is still in the Louvre today.

Years before, Constantijn Huygens, visiting the young Rembrandt and Jan Lievens in Leiden had exclaimed:

Oh, if only they could be acquainted with Raphael and Michelangelo, how eagerly their eyes would devour the monuments of these prodigious souls. How quickly they would surpass them all, giving Italians due cause to come to their own Holland. They claim to be in the bloom of their youth and wish to profit from it; they have no time to waste on foreign travel. Moreover, since these days the kings and princes north of the Alps avidly delight in and collect pictures, the best italian paintings can be seen outside Italy. What is scattered around in that country and only to be tracked down with great inconvenience, can be found here en masse so that one can have his fill.

A very down to earth and as it turned out valid argument, if only that the “kings and princes” were replaced by wealthy citizens who occasionally opened up their houses for painters and other privileged visitors. Ferdinand Bol once said that he habitually went to the homes of private collectors on Sundays, after church, of course. So, presumably, did Rembrandt.

The influence of the Baldassare Castiglione and Titian’s “Ariosto” on two Rembrandt self-portraits, the etched Self-portrait leaning on a stone sill of 1639 and the painted self-portrait of 1640 was first been noted by Hofstede de Groot in the early 20th century. It is interesting to note that already in the sketch made during or just after the Van Uffelen auction, Rembrandt deviated from the Raphael portrait. He was already thinking ahead: in particular, the beret’s position is changed, setting it at a jauntier angle than in Raphael’s painting and the body is slightly more turned. The slightly different body posture may also have been caused by the angle at which Rembrandt saw the portrait, sitting on his chair in the auction room. What must have appealed to him in particular was the self-confident pose of the figure of Castiglione and that of “Ariosto”, which he would put to full use in the painted self-portrait which shows him at the height of his powers at the age of 34, self-assured and in full command of his art.

Rembrandt, self-portrait, 1640, National Gallery

Parallels between Rembrandt’s pose in the etching and painting have more recently been related to an already prevailing tradition in Dutch portraiture and it may perhaps have been also influenced by Dürer’s 1498 self-portrait which he might have seen when Thomas Howard, who Earl of Arundel, who had taken it with him to England as a gift to King Charles I from the City of Nuremberg, had traveled home via the Netherlands.

In the costumes worn in both Rembrandt’s painting and etching too, Rembrandt seems to pay homage to illustrious predecessors. Indeed, the London self-portrait marks a high point in Rembrandt’s development towards a more authentic sixteenth-century costume. He wears a black tabbaard or gown with brown, striped sleeves and a collar trimmed with fur. Under that is a paltrock whose characteristic horizontal top edge is decorated with braid. Under the jerkin he wears a wambuis or doublet whose high, standing collar (as in the Castiglione portrait) can be seen at the neck. The shirt worn beneath the doublet has decorative smockwork at the neck and a small frill that is typical of the first thirty years of the sixteenth century, the age of Raphael. His bonnet is also one frequently seen in the early sixteenth century. Finally, in both the portrait and the etching he wears a chain with a crucifix around his neck – yet another allusion to pre-Reformation days.

The inventory drawn up at Rembrandt’s bankruptcy shows that he was, in as far a we know today, the only Amsterdam painter who possessed paintings by Raphael at the time. Only two other paintings were still in Amsterdam collections by the mid-17th century. One of Rembrandt’s Raphael paintings is described as een Maria beeltie van Raefel Urbijn (a painting of the Virgin by Raphael of Urbino) which hung in the back room or livingroom (Agtercaemer offte sael), the other, intriguingly, een tronie van Raefel Urbijn (a (male) portrait by Raphael of Urbino) which hung in the Sydelcaemer, the room next to the hall where Rembrandt received his clients. We do not know at what time Rembrandt acquired these paintings or the nature of the male portrait, so it is impossible to speculate on any possible influence on his own portraits or self-portraits. Significantly at the time of his bankruptcy he also owned four books with prints by or after Raphael against one by Titian.

Extract from Rembrandt’s bankruptcy inventory, 1657, showing the entry with the painting of the Virgin by Raphael, Amsterdam Stadsarchief

Rembrandt’s etching of 1639 and the 1640 painting constitute a singularly assertive declaration of personal dignity and self-confidence. He must have viewed this as an important opportunity for self-definition as well as self-promotion at a pivotal moment in his career. The etching of 1639 and painting of 1640 constitute a singularly assertive declaration of personal dignity and self-confidence. Clearly, he viewed both as an important project for self-promotion at this successful point in his career. He must have seen it as a practical response not only to inspiring examples of the past, but to competitive pressures in the present, hence the initial choice of the print medium, capable of being reproduced and widely circulated.

Rembrandt may well have approached Raphael’s portrait of Castiglione as an aesthetic model and as the likeness of a historical figure whose name he realised was significant. But more urgently, Rembrandt saw it as a valuable commodity. As the Van Uffelen sale had shown him, collectors who were purchasing “old master” paintings such as Raphael’s were paying far higher prices than they did for similar works by modern Dutch artists like himself. No wonder, then, that he determined to show, through creative emulation in his self-portraits, that he could rival and even surpass such precious objects from the past, taking up Huygens’ challenge to make the art of Holland equal to that of Italy.