Civic guards did not cease to exist in The Netherlands in their traditional form until 1903, but with Amsterdam’s economy waning during the last quarter of the 17th century, the civic guards’ golden age of sumptuous banquets, silver brocaded costumes and group portraits painted by the great masters was over. The headquarters of the three civic guards companies with their magnificently decorated Great Halls were given a different destination and the many group portraits reverted to the city while some were sold at auction. In a gradual process starting in 1683, paintings were transferred to the Town Hall. Group portraits from the Voetboogdoelen on the Singel were the first to be moved from their original location although not all at once: two of them were still seen in situ in 1753. Some of the paintings were sold at auction. The orphaned civic guards paintings satisfied two purposes: as appropriate decoration of the empty walls in the Town Hall and as a reminder of the glorious past.

That the paintings were welcomed at the Town Hall is shown by especially commissioned name plates listing the members in a specific civic guards painting. For instance, on 29 April 1687, one Jan Rosa is paid 84 guilders for “cleaning, painting, writing of names etc of and below the paintings in the War Council Room.” The oldest of the three name plates that have been preserved was made for Govert Flinck’s civic guards portrait of 1648.

Name plate (after 1683) for Govert Flinck’s 1648 civic guards portrait, wood, black varnish, gilding, 44x274x17 cm, Amsterdam Museum

Although there are several early books and documents on Amsterdam’s history, buildings, sites and institutions, tracking the whereabouts of civic guards group portraits in the 17th and 18th century is not easy. The most valuable of the contemporary descriptions are those by Gerard Schaep in an unpublished manuscript of 1653, the unpublished “Egerton Manuscript” of about the same time and, for our purpose, the book on the paintings in Amsterdam’s Town Hall, the Kunst- en historiekundige beschrijving en aanmerkingen over alle de schilderijen op het stadhuis te Amsterdam (Artistic and historical description and remarks on all paintings in Amsterdam’s Town Hall) by Jan Van Dyk, first published in 1758, on which the arrangement of civic guards paintings in the current exhibition in the Royal Palace (then the Town Hall) is based.

The Egerton Manuscript now in the British Library consists of watercolour copies of the group portraits in the Crossbowmen’s headquarters (Voetboogdoelen) commissioned by the guild’s governors. It is invaluable as the watercolours faithfully record the state of the paintings as they were in the mid-17th century. History has not been kind to them. Their original homes, the three headquarters of the civic guards companies, were, after all, not museums; the buildings were intensively used. Once the paintings left these buildings, they were often ruthlessly reduced in size to fit into their new homes.

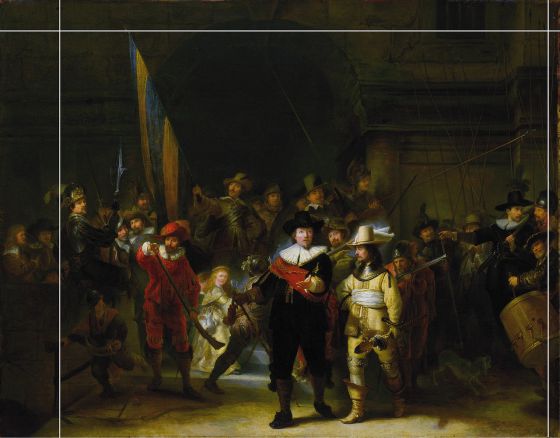

The story of Rembrandt’s Night Watch (1642), which was cropped on all sides to make it fit between two doors in the Small War Council Room at the Town Hall in 1715, is legendary but other paintings suffered even worse treatment. Aert Pietersz’ Civic Guards Meal of the Company of Pieter van Eck of 1604, for instance, only survives in three fragments as superimposing them on the watercolour copy in the Egerton manuscripts illustrates.

Another early painting, Cornelis Ketel’s Civic Guards Company of Captain Dirck Jacobsz Rosecrans en Lieutenant Pauw (1588), was reduced on all sides, particularly on the right where as much as 1.27 meters are thought to have been cut off.

Cornelis Ketel, Civic Guards Company of Captain Dirck Jacobsz Rosecrans en Lieutenant Pauw (1588), oil on canvas, 208×410 cm, Rijksmuseum. The men on the extreme right and left are only partially shown, a sign that the painting was cropped. The top of the flag missing as well as some of the feet suggests it was cropped above and below

Jan van Dyk (ca. 1690-1769) – the first professional restorer?

Jan van Dyk’s book on the Town Hall paintings is interesting for several reasons. With hardly any illustrations existing of the interior of the rooms of the building when it was still a functioning Town Hall, his book gives an idea about the paintings’ arrangement in 1758. Several paintings had been commissioned for the Town Hall, but with the city’s economy waning from the second half of the 17th century (as mentioned in earlier posts, the lunette paintings in the Town Hall’s galleries were never finished) paintings that had over time reverted to the city such as the civic guards portraits were moved to the Town Hall: a welcome opportunity to decorate the offices, halls and landings with portraits depicting men who had served the city honourably. The second edition of Van Dyk’s book, published posthumously in 1790, was intended to contain illustrations, but only two of them are known today. By that time the paintings must have been rehung as the civic guards paintings listed by Van Dyk in this room are not included.

In 1747 Van Dyk was employed by the city as restorer of the city’s paintings collection under the painter Jacob de Wit and he continued in this function until his death in 1769. As such he is sometimes seen as “the first professional restorer”, a claim that seems supported by his portrait by Jan ten Compe (1754) that shows him sitting at an easel while in the process of cleaning a landscape painting. But was he really?

Divisions were not as clear-cut then as they are now. Certainly Van Dyk stood at a turning point in art history: on the one hand he was a typical exponent of his time as an all-round 18th century artist; on the other he stood at the basis of the independent profession of restorer as we know it today. Significantly, perhaps, his profession on his death certificate is given as “artist”.

Van Dyk had been trained as a carpenter and gilder and may have left Amsterdam in 1707 to accompany his master to the House of Orange’s baroque castle Oranienstein in Dietz, Germany. There he gradually worked himself up to become court painter, restorer, connoisseur, appraiser and drawing instructor. Between 1710 and 1716 he executed eleven ceiling paintings in Oranienstein, the only paintings by him that survive today. They are competent but lack artistic merit. Although not a very successful artist himself, he nevertheless appears to have enjoyed the appreciation of the court which enabled him to secure such an important commission and in 1735 he was appointed overseer of all palaces and public building in the counties of Diez and Beilstein by the future Stadtholder Prince Willem IV.

Back in Amsterdam, Van Dyk came to devote more and more of his time t0 restorations, in particular cleanings, and from his writings it appears that he certainly did not regard the work as inferior. He saw it as his mission to rescue “badly mistreated paintings” from the “claws” of the “Know-nothings of Art”. He also remained in the court’s employ: during his tenure as city restorer he was also commissioned to restore the paintings in the Hall of Orange in The Hague about which he published a book entitled Beschrijving der schilderijen in de Oranjezaal van het Vorstelijk Huys in ‘t Bosch (Description of the paintings in the Hall of Orange of the Noble Huys ten Bosch), 1769.

Van Dyk and the civic guards paintings in the Town Hall

Van Dyk’s book on the Town Hall covers all the paintings located there in 1758, including chimney pieces by (among others) Bol and Flinck, ceiling and wall paintings and the lunette paintings in the galleries, but he clearly thought the civic guards paintings of special importance. The men depicted in these portraits, he writes in his foreword, “are people from our city who have not only girded the sword but many of them did not spare themselves to cast the Spanish Yoke from their shoulders”, a reference to the Eighty Years Revolt of the Dutch Provinces against Spain which had ended in 1648.

In his foreword Van Dyk deplores the compromised condition of the civic guards group paintings in his care: “Many old Jewels of Art, ruined by bunglers’ hands, or better: ignorant claws, […] that are so abraided that one can see the wooden panel through the paint.” He calls these “bunglers” “evil spirits” and “bastards” and on one occasion expresses gratitude towards his employer, Mayor Pieter Rendorp, for having rescued three civic guards group paintings that had suffered damage at the time of their sale. The historian Jan Wagenaar also remarks on this incident in his books on the city published between 1760-1767, stating that the damage had occurred at the time of the public auction of the paintings “or some other public gathering”. Not only, says Van Dyk, did these “evil spirits” ruin “the best pieces” but instead of restoring them, they had made their condition “far worse”; it seemed as if they had “conspired with Satan to completely destroy the much loved ancient art works and so one is justified in crying instead of O Tempera, O Mores: O Times, O Bunglers!”

Badly abraided and overpainted 16th century civic guards portrait, painter unknown, oil on panel, 112×204 cm, Amsterdam Museum

Unfortunately Van Dyk gives no insight in his own restoration methods or the solvents he uses to clean paintings. Concerning Rembrandt’s Night Watch he writes that he has removed “the many oils and varnishes applied to it over time” so that the men can once more be seen. In particular he is pleased with the fact that the names on the shield on the right are once more legible so that the members of the company can be identified. He erroneously assumed that these names were written by Rembrandt himself: the shield is a late 17th addition by an unknown artist. Van Dyk describes Rembrandt’s masterpiece in glowing terms:

Rembrandt, Civic guards of District II of the Kloveniers, led by Captain Frans Banninck Cocq, known as the “Night Watch”, 1642, oil on canvas, today measuring 379.5×453.5 m, Rijksmuseum

This painting is admirable because of its great force and its brushwork; it is [like] a strong sunlight, the paint very thickly applied, and it is remarkable that with such forceful brushwork nevertheless such great refinement could have taken place, because on the embroidery on the Lieutenant’s uniform the paint stands up so high that one could grate nutmegs on it and Amsterdam’s emblem held by a lion [is] so neat and delicate as if it were finely painted. The face of the drummer seen up closely is exceptionally nicely done. It is to be regretted that this piece has been so much reduced in order for it to be placed between two doors.

Another painting, the Officers and other Civic Guards of District XI in Amsterdam under Captain Reijnier Reael and Lieutenant Cornelis Michielsz Blaeuw (dated 1637 on the painting), begun by the Haarlem painter Frans Hals and, after Hals left Amsterdam abruptly never to return, finished by Pieter Codde, elicits from him the following comments that inadvertently launched the painting’s nickname, the Meagre Company, by which it has become known ever since:

This painting is of entirely different nature as all the others because when one looks at it closely it appears as if it is painted immediately on the canvas without grounding. Because it is painted very rapidly [it is] very beautifully drawn, the poses of the figures are so wonderful as is the entire composition [and] the funny thing is that they are all so thin and withered that one would be justified in calling them the Meagre Company. The ensign [the figure on the extreme left] has such a cheerful countenance that his face convinces everyone that he must have been quite a merrymaker. The piece contains thirteen figures but without names.

Frans Hals and Pieter Codde, the “Meagre Company”, date inscribed “Ao 1637”, oil on canvas, 209×429 cm, Rijksmuseum

Indeed, there are no inscriptions on the painting and no name plate for this painting has survived. Attempts have been made to identify the men in the Meagre Company by comparing their faces with contemporary portraits of known sitters, though not convincingly. There has been a suggestion, for instance, that Van Dyk’s “merrymaker” could be Nicolaes van Bambeeck, portrayed by Rembrandt about a decade later.

The second person from the right has been very tentatively identified as Jean Pellicorne, of whom two other contemporary portraits exist.

A “peculiar piece”

On 17th century civic guards portraits the men are generally shown in an interior or posing in an urban setting in front of a building associated with that particular company. One exceptional civic guards portrait that, as far as I know, is the only one situated outside Amsterdam, is that by Nicolaes Lastman, brother of the more famous Pieter. The painting was completed by Adriaen van Nieulandt in 1623. It originally hung in the Crossbowmen’s headquarters on the Singel where it was noted by Gerard Schaep in 1653 as hanging in the “other upper chamber, called Saint George”. In Van Dyk’s time, 1758, it hung in the Large War Council Room at the Town Hall.

Nicolaes Lastman and Adriaen van Nieulandt, Civic guards company under Captain Abraham Boom and Lieutenant Oetgens van Waveren, 1623, oil on canvas, 245×572 cm, Amsterdam Museum

Van Dyk notes:

There is something peculiar about this piece in that these persons apparently have been portrayed in front of an earthwork that can be seen in the distance, so that one cannot just guess, but certainly believe, that these men have been in the Field, and probably did something praiseworthy near or in front of an earthwork.

Detail showing the now illegible piece of paper, the earthwork and the men once more in the background

As usual he complains that “imprudent cleaning” has erased the text that was no doubt written on the paper painted in the foreground. He is unable, therefore, to ascertain who these men were, what their mission was, or who painted them.

As to the “peculiarity” of the painting, Van Dyk was absolutely right as already noted by Schaep in 1653:

Ao 1623 […] 9 or 10 persons from head to toe, being Captain Abram Boom, Lieutenant Lut. Ant. Oetges. Which piece was started by Lasman [Nicolaes Lastman] but due to his death was completed by Nuland [Adriaen van Nieulandt]. This company had been outside the city in a garrison in Swoll [Zwolle].

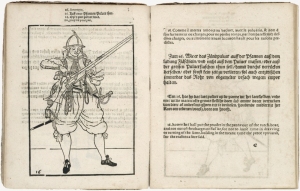

After the Twelve Year Truce had ended, the fighting between Spain and the Provinces had resumed and many guardsmen answered the call to help defend other cities. The men in Lastman’s and Van Nieulandt’s painting were volunteers who, led by Captain Abraham Boom, had marched to Zwolle in 1622 for that purpose. The guards had been recruited from various Districts of the Amsterdam Crossbowmen’s company: Captain Boom (the man in black), for instance, was Captain in District IX while the Lieutenant (here holding a partisan) was lieutenant in District XVII. The group portrait was clearly meant to commemorate the campaign. The men are not depicted realistically in the sense that their costumes in the painting were modeled on the Wapenhandelinghe, a military handbook with copper engravings by Jacob de Gheyn II published in 1607. In the background on the right we see the men once more, grouped close to the earthwork with their flag.

(Partial) copies

The mission of the volunteers was apparently so memorable to the participants that they commissioned at least three individual portraits copied from it for their private homes. One of these was painted by the young Delft painter Antonie Palamedesz and is dated 1626. It represents a young Willem Backer who would later be the head of one of Amsterdam’s Regent families. Another partial copy, of the second man from the right, is tentatively attributed to Adriaen van Nieulandt who finished the original group portrait. A note on its back identifies the guard as Ferdinand van Schuylenburgh. The copies differ from the group portrait in that their costumes have been slightly updated, particularly their collars, and that they show more of the landscape around Zwolle. A third copy, portraying Captain Abraham Boom, is known to exist as well.

An interesting small copy of the Kloveniers civic guards of District V led by Captain Cornelis de Graeff and Lieutenant Hendrick Lauwrensz painted by Jacob Adriaensz Backer (1642) shows two young boys who were no doubt added upon the request of the unknown guardsman who commissioned it. In Van Dyk’s time the original hung in the Small War Council Room and it caused some confusion as people believed it to be by Rubens. Van Dyk correctly gives Backer as the artist who painted it.

Werner van den Valckert, “Wapenhandelinghe” and the Prince of Orange

The Wapenhandelinghe engraved by Jacob de Gheyn II (1565-1629) plays a role in several civic guards group paintings including Rembrandt’s Night Watch. It is also explicitly present in another early civic guards painting: Werner van den Valckert’s Civic Guards Company of Captain Coenraetsz Burgh and Lieutenant Pieter Evertsz Hulft, signed and dated on a lance “Warner v. Valckert f: 1625”, and also dated on the mantlepiece: “ANNO 1625”. In spite of the signature Van Dyk, who in all probability was not familiar with this painter, attributes it to “Moreelse” (the Utrecht painter Paulus Moreelse) which he does with several other civic guards portraits the painters of which are no longer known to him.

Werner Jacobsz van den Valckert, Civic Guards Company of Captain Albert Coenraetsz Burgh and Lieutenant Pieter Evertsz Hulft, 1625, oil on panel, 169.5x 270 cm, Amsterdam Museum

Werner van de Valckert (1585-1627) was a renowned painter and engraver in his time but already in Van Dyk’s time all but forgotten. Like most Amsterdam painters he lived and worked in the newly developed district outside Saint Anthony’s city gate, the Sint Anthoniebreestraat, and it is assumed that most civic guards portraits were painted in this district. What strikes one about his group portrait is its composition which is compact, yet each individual (who would separately have paid for their inclusion in the group portrait) is given ample space and attention. Prominently in the center of the composition is ensign Arent Willemsz van Buyl, whose figure divides the composition in two. The sergeant on the right hands a note with the names of the sitters to his captain, a painterly device that connects the two sides of the composition.

Captain Burgh and his Lieutenant, the brewer Hulft, are the only ones shown seated, which confirms the customary hierarchy. The men were entrusted with guarding and keeping order in District VIII of the Crossbowmen’s company. Burgh indicates the area on a map. The officers on the left thereby seem to emphasise that they will guarantee the continued security in their District. One of the men on the right confirms the group’s military prowess: he points emphatically at a copy of De Gheyn’s Wapenhandelinghe. The book had been commissioned by Prince Maurits of Orange so that its inclusion in the painting also confirmed the men as supporters of the Prince, as does the Stadtholder’s escutcheon on the flag. This is not surprising as both the Captain and his Lieutenant owed their appointments as members of the city council to the Prince.

In general it is unclear on what occasion Amsterdam civic guards portraits were commissioned. In Haarlem, for instance, it was customary for militia officers, who served according to a rota, to have their portraits painted as a group when they stood down from their posts but in Amsterdam this practice did not exist. Quite possibly Maurits’ death in 1625 may have initiated the commission for this group portrait.

“In all their glory” – a different perspective

In 1650 the young Stadtholder Willem II converged thousands of cavalry on Amsterdam following a bitter power struggle with the Province of Holland and the powerful Regents of Amsterdam. The town council, hastily summoned by Burgomaster Bicker, decided to “mobilise the citizenry.” These, “amply supplied with shot, gunpowder and lunt, spread out to all the city gates.” Among them were 340 members of the peat-carriers’ guild, less well-off citizens who, unlike the civic guards, could not afford fire arms and were therefore supplied with hitting and stabbing weapons as is stated on the contemporary frame: “In the year sixteen hundred forty ten. Then the Prince’s forces in front of Amsterdam were seen. Anno 1652” (top) and “Our guild three hundred forty strong, both young and old in years. The government supplied us as well with broad-swords and long spears” (bottom). “It was a miracle how eager everyone was to defend the city”, observed the Hollantze Mercurius in its 1651 annual overview of notable events in Europe.

M. Engel, The arming of the peat-carriers’ guild in 1650, oil on panel, 565×176 cm, Amsterdam Museum

The attack was repulsed and the peat-carriers, clearly proud of their role as defenders of the city’s freedom, had themselves immortalised in 1652 posing on Dam Square with their peaks and swords. Unlike the distinguished members of the civic guards who could afford master painters like Van der Helst and Rembrandt, the peat-carriers had to make do with the obscure painter “M. Engel” by whom no other paintings are known. The painting would never have been deemed worthy to decorate the hallowed offices in the Town Hall and Jan van Dyk never saw it, although he would certainly have appreciated their heroic stance. Stiff and primitive in its execution as the painting may be, certainly when measured against the artistic standard of the day, it nevertheless leaves us a unique record of the brave peat-carriers at a crucial episode in Amsterdam’s history. “In All their Glory” is certainly a phrase covering more than one meaning.

Note:

Exhibition “In All Their Glory”, Summer exhibition at the Royal Palace Amsterdam until 31 August 2014

The exhibition “In All Their Glory” is on view at Amsterdam’s Royal Palace. Informative website here. It offers a reconstruction of the Large and Small War Council Rooms with their civic guards paintings as Jan van Dyk saw them in 1758. The reconstruction is largely limited to the Large War Council Room; a reconstruction of the Small War Council Room is problematic since Van Dyk’s descriptions of the paintings is not always clear and some of the paintings are meanwhile lost.

See also part (1) for the early history of Amsterdam’s civic guards portraits, here.

Relevant sources (selected):

- Schaep, Gerard (Gerrit Pietersz) (manuscript), “Record and list of the public paintings kept at the three civic guard halls: as I have found them, after my return to Amsterdam in February 1653”, Amsterdam City Archives. I have used the transcription in Pieter Scheltema, “De schilderijen in de drie doelens te Amsterdam, beschreven door G. Schaep, 1653,” in Aemstel´s oudheid of gedenkwaardigheden van Amsterdam, vol. 7 (1885). Unfortunately Scheltema was not able to decypher the entire text

- Jan van Dyk, Kunst- en historie-kundige beschryving van alle de schilderyen op het stadhuis van Amsterdam, Amsterdam 1758

- Jan Wagenaar, Amsterdam in zyne opkomst, aanwas, geschiedenissen, voorregten, koophandel, gebouwen, kerkenstaat, schoolen, schutterye, gilden en regeeringe, beschreeven, 1760–67

- Jan Six and W. Del Court, “De Amsterdamsche Schutterstukken”, Oud Holland 21 (1903), which offers a description of the Egerton Manuscript (BL MS Eg. 983)

- W.F.H. Oldewelt, “Eenige posten uit de thesauriersmemorialen van Amsterdam van 1664 tot 1764”, Oud Holland 51 (1934)

- J. Bos, “Capitaele stucken. De lotgevallen van zeven belangrijke schilderijen uit het bezit van de stad”, Jaarboek Amstelodamum 88 (1996)